A Hindu-American Lawyer’s Quest

Sai Santosh Kumar Kolluru

Photo by Jason Sung on Unsplash

Om Hreem Shree Gurubhyo Namah1 Salutations to all the Gurus (saints and sages of all traditions) who deliver us from darkness to light.

Introduction

Swami Vivekananda’s famous speech at the Parliament of World Religions in 1893 introduced Hinduism2Prior to the western digestion of “Hinduism,” Hinduism was known as Sanātanā Dharma or Eternal Truth. to the West. As an ambassador of one of the most ancient traditions of the world, he conveyed the essence of the Vedas, the universal acceptance of all traditions: “as the different streams having their sources in different places…all lead to Thee.” (Rig Veda -1.164.46). 3Ékaṃ sád víprā bahudhâ vadanti – “Truth is One, the Sages give it many names.” Rig Veda (1.164.46). 127 years later much has changed in the West. A million plus Hindus live in the United States. Words like karma, yoga, and mantra are part of everyday vocabulary. Indeed, public opinion on God and Life are turning Hindu. With this influence of the East, I’ve always wondered how and what, if any, that influence has on the Hindu-Americans professionals that now dominate both the private and public sectors, particularly in the legal profession.

As a Hindu-American lawyer myself, I invite you to explore this question from my perspective. First, I examine my Hindu identity: what being Hindu means to me. Second, I examine my identity as a lawyer: what being a lawyer means to me. Last, I examine the influence of my spiritual practice (sadhana) to attain liberation (mokṣa), the ultimate state of freedom from all sorrow (ātyantika-duḥkha-nivṛtti), on my role as a lawyer. I rely on the revelations of the Upaniṣads, discourses and dialogues of self-realized seers (Rishis), and the practical teachings of the Bhagavad Gītā, a 700-verse dialogue in the epic Mahabharata, as my Vedantic references. I also rely on the writings of Mahatma Gandhi, perhaps the most well-known Hindu lawyer. I hope that this essay provides a starting point for introspection for Hindu-American lawyers everywhere.

My Hindu Identity

I was named after an incarnation of the Divine Mother, Santoshi Mata, and after a famous Hindu and Muslim Saint, Sai Baba of Shirdi. Growing up, there was a devotional song (bhajan) my family would sing – You are Allah, You are Jesus, You are Zoroaster and Buddha, You are my Ram, and You are my Rahim (“Allah Tum Ho, Yeshu Tum Ho, Zoroastria Bhi Ho, Mahavir Tum Ho, Gautama Buddha Karim, Mere Ram, Mere Ram, Ram Rahim”). The pluralism in my name and the universal appeal of my tradition shaped my Hindu identity, and sparked devotion (Bhakti) in my heart early on. This identity drove me to ask the two most fundamental questions of my life: who am I? and what is my purpose? To answer the first question, the Upaniṣadic teaching of non-duality (a-dvaita) of the individual self (Jīva) and the Total Self (Brahman) introduced me to the school of Advaita Vedanta.4 “In Hinduism, there are three systems of thought that its followers generally fall into: Dualism, Qualified Non-Dualism, and Absolute Non-Dualism – Dvaita, Visishtadvaita, and Advaita. Wherever an individual in his or her spiritual and religious practice falls within these three systems, the systems represent the individuals progress towards the Ultimate Reality. They are understood not as contradictory but complementary and suited to different temperaments. For the ordinary man with strong attachment to the senses, a dualistic form of religion, prescribing a certain amount of material support, such as music and other symbols, is useful. A man of God-realization transcends the idea of worldly duties, but the ordinary mortal must perform his duties, striving to be unattached and to surrender the results to God. The mind can comprehend and describe the range of thought and experience up to the Visishtadvaita, and no further. The Advaita, the last word in spiritual experience, is something to be felt in samādhi, for it transcends mind and speech.” Gupta, Mahendranath, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, trans. Swami Nikhilananda. (New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1942), 39. The Upaniṣads declare, “I am not the finite conditionings that constitute the individual identity, I am Brahman alone.”5 Brihadaranyaka Upaniṣad (1.4.10); Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad (3.2.9); Kena Upaniṣad (1.3), among others. This means to even shed the finite conditioning that “I am a Hindu.” To realize this Truth, the Gītā became my practical guide. The idea that I can both be a seeker of Truth and play an active role in this world (karma-yoga) drew me to the Gītā. This in turn led me to answer my second question: to be a lawyer.

My Identity as a Lawyer

I still remember the day my father told me we were going to America. At the age of nine, I entered a world of abundance and opportunity. Fifteen years later, this journey led me to law as a career. I realized that I can use law as an instrument to have an immediate impact on someone’s life for the better. Throughout law school, I channeled this passion to help those in need; I petitioned for an immigration law clinic, wrote editorials on pressing issues, began my journey as a public servant interning and externing at various government agencies and non-profits, and attempted to bridge Eastern wisdom with Western thought as a member of the Journal of Law and Religion. Ultimately, for me, becoming a lawyer meant that I could bring the same yearning for the Truth, to serve the world through the legal profession.

Hindu Identity and the American Lawyer

Just as a spiritual seeker (sādhak) is engaged in a lifelong search for the Truth, a lawyer as an officer of the court participates in the search for Truth as well. The American Bar Association’s preamble well describes the mission of the American Lawyer, which includes the primary responsibility to “zealously assert[] the client’s position under the rules of the adversary system.” We hope in the American legal system that if both sides follow this mission to the best of their ability, the truth will come out.

At an initial glance, the preamble’s use of zealous and adversary system seems incongruous with the path of karma-yoga; how can my life’s journey to attain the Ultimate possibly benefit from my actions (karma) in the legal profession if I am supposed to present my client’s version of the truth and, by default, develop a personality of hostility? It is no surprise then a Hindu lawyer often subscribes to legal ethics over religious ethics, but this is not necessary. The Hindu tradition has a place in the practice of law, and it is not focused on shaping the law or the legal profession by establishing “Hindu Courts” or “Hindu Law,” it is focused entirely on transforming the individual’s ordinary mind.

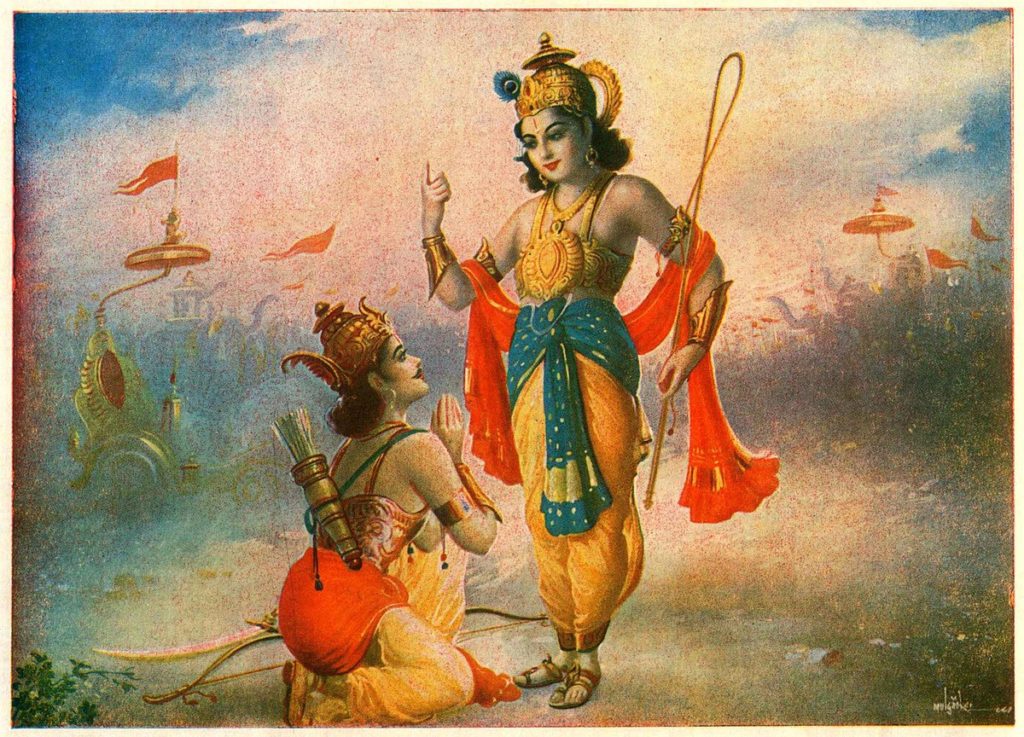

Take for example Arjuna in the Gītā. Upon entering the battlefield of Kurukshetra, his mind overcomes with doubt and sorrow when he sees his family and friends on the other side, and he becomes unwilling to do his duty as a warrior on the righteous side. Bhagavan Krishna’s response to Arjuna places a central emphasis on the mind throughout the Gītā: work hard and do your duty in the world without any selfish attachment, so that you can gradually attain freedom from the bondage of selfish conditioning. Bhagavan tells us to remain in the world, play an active role, and immerse in all activities without the desire for the fruits of your actions (niṣkāmakarma). (2.47). While some seek material renunciation, Bhagavan emphasizes being in the world with mental renunciation. He explains, “true renunciation is giving up all results of one’s actions for personal reward.” (18.11). With this attitude, in the crucible of the courtroom or the boardroom, the selfish mind is tested and transformed into a selfless mind. In that state, gradually, a Hindu lawyer attains mental equanimity (sthitaprajna). (2.38; 2.54-57). With no selfish motive, a Hindu lawyer dedicates all actions and results to the highest ideal, and work becomes worship. Such a mind slowly sees the omnipresent Divine (with or without form) in oneself and in everything. This is the practical message of the Gītā to a Hindu lawyer.

How can my life’s journey to attain the Ultimate possibly benefit from my actions (karma) in the legal profession if I am supposed to present my client’s version of the truth and, by default, develop a personality of hostility?

Gandhi understood this message of the Gītā. In twenty years as a barrister, he was known for his extraordinary commitment to Truth (satyam). He understood that he had a duty (Dharma) to his clients and the court, and that the practice of Truth was the standard by which he judged that duty. Regarding the function of a lawyer, he stated, “the true function of a lawyer was to unite parties riven asunder.”6Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand, An Autobiography- The Story of My Experiments with Truth (1959), 97. With the ethics of the Gītā in his heart, he brought about many private compromises.7 Id. In the process, he writes, “I lost nothing thereby-not even money, certainly not my soul.”8 Id.

In conclusion, for a Hindu, the Upaniṣadic revelation that I am Brahman can be realized by the ethical and practical guidance of the Gītā: do your duty with an attitude of selfless service for the benefit of the world (loka-saṅgraham). (3.20-21). For a Hindu lawyer, the legal profession is fertile ground to put the ideals of the Gītā, particularly the path of karma-yoga, into practice: zealously and selflessly represent a client at every step without desire for fruits that follow each action. The practice of law then becomes a personal act of worship, and thus, helps a Hindu lawyer not only find fulfillment in the temporal world but also attain liberation (mokṣa) from that world. ♦

The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of DoD or its Components.

Sai Santosh Kumar Kolluru is an Emory Law graduate ’18L, and a former member of the Journal of Law and Religion. He is a practicing attorney in Washington, D.C., and a student of Yoga and Vedanta.

Recommended Citation

Kolluru, Sai Santosh Kumar. “A Hindu-American Lawyer’s Quest.” Canopy Forum, September 2, 2020. https://canopyforum.org/2020/09/02/a-hindu-american-lawyers-quest/