The First Word: To Be Human is to be Free

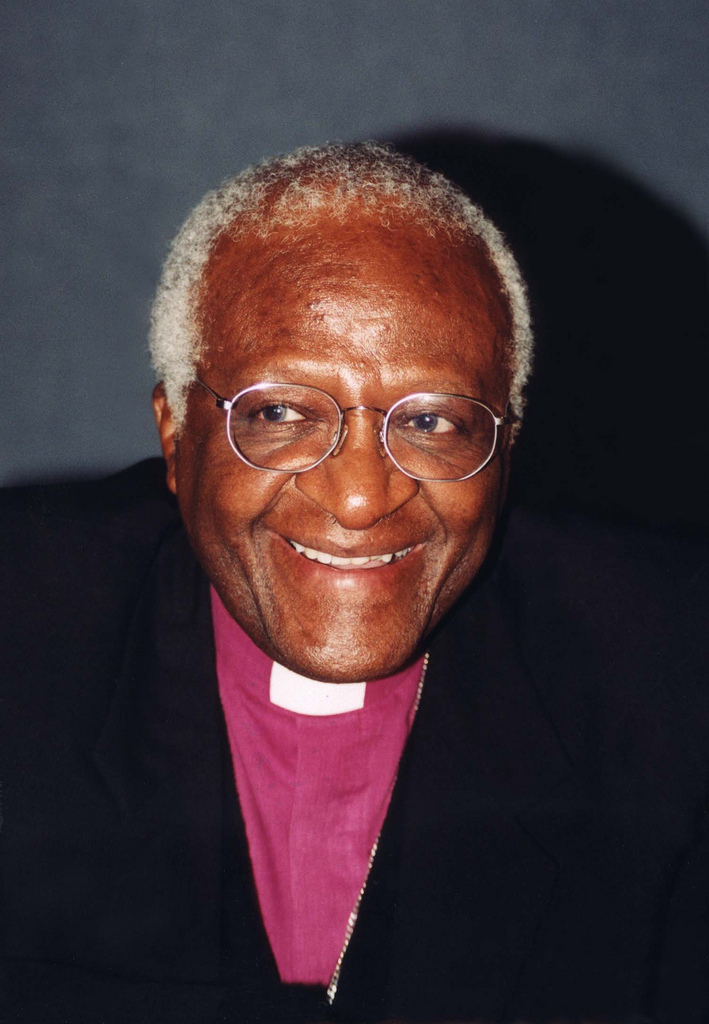

Desmond M. Tutu

Photo by kylefromthenorth on Unsplash.

We at Canopy Forum join the world in lamenting the recent death and celebrating the remarkable life of Archbishop Desmond M. Tutu. The following text is based on a keynote lecture that Archbishop Tutu offered to conclude the international conference on “Christianity and Democracy in Global Context,” November 11-14, 1991, convened by the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University. The Archbishop later revised the text for publication as a foreword to John Witte, Jr. and Frank S. Alexander, eds., Christianity and Human Rights (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1-7.

There is a story, which is fairly well known, about when the missionaries came to Africa. They had the Bible and we, the natives, had the land. They said “Let us pray,” and we dutifully shut our eyes. When we opened them, why, they now had the land and we had the Bible. It would, on the surface, appear as if we had struck a bad bargain, but the fact of the matter is that we came out of that transaction a great deal better off than when we started. The point is that we were given a priceless gift in the Word of God: the Gospel of salvation, the good news of God’s love for us that is given so utterly unconditionally. But even more wonderful is the fact that we were given the most subversive, most revolutionary thing around. Those who may have wanted to exploit us and to subject us to injustice and oppression should really not have given us the Bible, because that placed dynamite under their nefarious schemes.

The Bible makes some quite staggering assertions about human beings which came to be the foundations of the culture of basic human rights that have become so commonplace in our day and age. Both creation narratives in Genesis 1-3 assert quite categorically that human beings are the pinnacle, the climax, of the divine creative activity; if not climactic, then central or crucial to the creative activity. In the first narrative the whole creative process moves impressively to its climax which is the creation of human beings. The author signals that something quite out of the ordinary is about to happen by a change in the formula relating to a creative divine action. Up to this point God has merely had to speak “Let there be. . . .” and by divine fiat something comes into being ex nihilo. At this climactic point God first invites his heavenly court to participate with him, “Let us create man in our image” (Gen. 1:26). Something special has come into being.

Remarkably this narrative is, in fact, in part intended to be a jingoistic propaganda piece designed to lift the sagging spirits of a people in exile whose fortunes are at a low ebb, surrounded as they are by the impressive monuments to Babylonian hegemony. Where one would have expected the author to claim that is was only Jews who were created in the image of God, this passage asserts that it is all human beings who have been created in the divine image.

That this attribute is a universal phenomenon was not necessarily self evident. Someone as smart as Aristotle taught that human personality was not universally possessed by all human beings, because slaves in his view were not persons. The biblical teaching is marvelously exhilarating in a situation of oppression and injustice, because in that situation it has often been claimed that certain groups were inferior or superior because of possessing or not possessing a particular attribute (physical or cultural). The Bible claims for all human beings this exalted status that we are all, each one of us, created in the divine image, that it has nothing to do with this or that extraneous attribute which by the nature of the case, can be possessed by only some people.

The consequences that flow from these biblical assertions are quite staggering. First, human life (as all life) is a gift from the gracious and ever generous Creator of all. It is therefore inviolable. We must therefore have a deep reverence for the sanctity of human life. That is why homicide is universally condemned. “Thou shalt not kill” would be an undisputed part of a global ethic accepted by the adherents of all faiths and of none. For many it would include as an obvious corollary the prohibition of capital punishment. It has seemed an oddity that we should want to demonstrate our outrage that, for example, someone had shown scant reverence for human life by committing murder, by ourselves then proceeding to take another life. In some ways it is an irrational obscenity.

The life of every human person is inviolable as a gift from God. And since this person is created in the image of God and is a God carrier a second consequence would be that we should not just respect such a person but that we should have a deep reverence for that person. The New Testament claims that the Christian person becomes a sanctuary, a temple of the Holy Spirit, someone who is indwelt by the most holy and blessed Trinity. We would want to assert this of all human beings. We should not just greet one another. We should strictly genuflect before such an august and precious creature. The Buddhist is correct in bowing profoundly before another human as the God in me acknowledges and greets the God in you. This preciousness, this infinite worth is intrinsic to who we all are and is inalienable as a gift from God to be acknowledged as an inalienable right of all human persons.

The Babylonian creation narrative makes human beings have a low destiny and purpose — as those intended to be the scavengers of the gods. Not so the biblical Weltanschauung which declares that the human being created in the image of God is meant to be God’s viceroy, God’s representative in having rule over the rest of creation on behalf of God. To have dominion, not in an authoritarian and destructive manner, but to hold sway as God would hold sway — compassionately, gently, caringly, enabling each part of creation to come fully into its own and to realize its potential for the good of the whole, contributing to the harmony and unity which was God’s intention for the whole of creation. And even more wonderfully this human person is destined to know and so to love God and to dwell with the divine forever and ever, enjoying unspeakable celestial delights. Nearly all major religions envisage a post mortem existence for humankind that far surpasses anything we can conceive.

All this makes human beings unique. It imbues each one of us with profound dignity and worth. As a result to treat such persons as if they were less than this, to oppress them, to trample their dignity underfoot, is not just evil as it surely must be; it is not just painful as it frequently must be for the victims of injustice and oppression. It is positively blasphemous, for it is tantamount to spitting in the face of God. That is why we have been so passionate in our opposition to the evil of apartheid in South Africa. We have not, as some might mischievously have supposed, been driven by political or ideological considerations. No, we have been constrained by the imperatives of our biblical faith.

In the face of injustice and oppression it is to disobey God not to stand up in opposition to that injustice and that oppression.

Any person of faith has no real option. In the face of injustice and oppression it is to disobey God not to stand up in opposition to that injustice and that oppression. Any violation of the rights of God’s stand-in cries out to be condemned and to be redressed, and all people of good will must willy-nilly be engaged in upholding and preserving those rights as a religious duty. Such a discussion as this one should therefore not be merely an academic exercise in the most pejorative sense. It must be able to galvanize participants with a zeal to be active protectors of the rights of persons.

The Bible points to the fact that human persons are endowed with freedom to choose. This freedom is constitutive of what it means to be a person — one who has the freedom to choose between alternative options, and to choose freely (apart from the influences of heredity and nurture). To be a person is to be able to choose to love or not to love, to be able to reject or to accept the offer of the divine love, to be free to obey or to disobey. That is what constitutes being a moral agent.

We cannot properly praise or blame someone who does what he or she cannot help doing, or refrains from doing what he or she cannot help not doing. Moral approbation and disapproval have no meaning where there is no freedom to choose between various options on offer. That is what enables us to have moral responsibility. An automaton cannot be a moral agent, and therein lies our glory and our damnation. We may choose aright and therein is bliss, or we may choose wrongly and therein lies perdition. God may not intervene to nullify this incredible gift in order to stop us from making wrong choices. I have said on other occasions that God, who alone has the perfect right to be a totalitarian, has such a profound reverence for our freedom that He had much rather we went freely to hell than compel us to go to heaven.

An unfree human being is a contradiction in terms. To be human is to be free. God gives us space to be free and so to be human. Human beings have an autonomy, an integrity which should not be violated, which should not be subverted. St. Paul exults as he speaks of what he calls the “glorious liberty of the children of God” (Rom. 8:21) and elsewhere declares that Christ has set us free for freedom. It is a freedom to hold any view or none — freedom of expression. It is freedom of association because we are created for family, for togetherness, for community, because the solitary human being is an aberration.

Human beings have an autonomy, an integrity which should not be violated, which should not be subverted.

We are created to exist in a delicate network of interdependence with fellow human beings and the rest of God’s creation. All sorts of things go horribly wrong when we break this fundamental law of our being. Then we are no longer appalled as we should be that vast sums are spent on budgets of death and destruction, when a tiny fraction of those sums would ensure that God’s children everywhere would have a clean supply of water, adequate health care, proper housing and education, enough to eat and to wear. A totally self-sufficient human being would be subhuman.

Perhaps because of their own experience of slavery, the Israelites depicted God as the great liberator, and they seemed to be almost obsessed with being set free. And so they had the principle of Jubilee enshrined in the heart of the biblical tradition. It was unnatural for anyone to be enthralled to another, and so every fifty years they celebrated Jubilee, when those who had become slaves were set at liberty. Those who had mortgaged their land received it back unencumbered by the burden of debt, reminding everyone that all they were and all they had was a gift, that absolute ownership belonged to God, that all were really equal before God, who was the real and true Sovereign.

That is the basis of the egalitarianism of the Bible — that all belongs to God and that all are of equal worth in His sight. That is heady stuff. No political ideology could better that for radicalness. And that is what fired our own struggle against apartheid — this incredible sense of the infinite worth of each person created in the image of God, being God’s viceroy, God’s representative, God’s stand-in, being a God carrier, a sanctuary, a temple of the Holy Spirit, inviolate, possessing a dignity that was intrinsic with an autonomy and freedom to choose that were constitutive of human personality.

This person was meant to be creative, to resemble God in His creativity. And so wholesome work is something humans need to be truly human. The biblical understanding of being human includes freedom from fear and insecurity, freedom from penury and want, freedom of association and movement, because we would live ideally in the kind of society that is characterized by these attributes. It would be a caring and compassionate, a sharing and gentle society in which, like God, the strongest would be concerned about the welfare of the weakest, represented in ancient society by the widow, the alien, and the orphan. It would be a society in which you reflected the holiness of God not by ritual purity and cultic correctness but by the fact that when you gleaned your harvest, you left something behind for the poor, the unemployed, the marginalized ones — all a declaration of the unique worth of persons that does not hinge on their economic, social, or political status but simply on the fact that they are persons created in God’s image. That is what invests them with their preciousness and from this stem all kinds of rights.

All the above is the positive impact that religion can have as well as the consequences that flow from these fundamental assertions. Sadly, and often tragically, religion is not often in and of itself necessarily a good thing. Already in the Bible there is ample evidence that religion can be a baneful thing with horrendous consequences often for its adherents or those who may be designated its unfortunate targets. There are frequent strictures leveled at religious observance which is just a matter of external form when the obsession is with cultic minutiae and correctness. Such religion is considered to be an abomination, however elaborate the ritual performed. Its worth is tested by whether it has any significant impact on how its adherents treat especially the widow, the orphan and the alien in their midst. How one deals with those who have no real clout and who can make no claim on being given equitable and compassionate treatment, becomes a vital clue to the quality of religiosity.

We must hang our heads in shame, however, when we survey the gory and shameful history of the Church of Christ. There have been numerous wars of religion instigated by those who claimed to be followers of the One described as the Prince of Peace. The Crusades, using the cross as a distinctive emblem, were waged in order to commend the Good News of this Prince of Peace amongst the infidel Muslims, seeking to ram down people’s throats a faith that somewhere thought it prided itself on the autonomy of the individual person freely to choose to believe or not to believe. Religious zealots have seemed blind to the incongruity and indeed contradiction of using constraint of whatever sort to proclaim a religion that sets high store by individual freedom of choice. Several bloody conflicts characterize the history of Christianity, and war is without doubt the most comprehensive violation of human rights. It ignores reverence for life in its wanton destruction of people. It subverts social and family life and justifies the abrogation of fundamental rights.

Christians have waged wars against fellow Christians. St. Paul was flabbergasted that Christians could bring charges against fellow Christians in a court of law. It is not difficult to imagine what he would have felt and what he would have said at the spectacle of Christians liquidating fellow Christians as in war. Christians have been grossly intolerant of one another as when Christians persecuted fellow Christians for holding different views about religious dogma and practice. The Inquisition with all that was associated with it is a considerable blot on our copybook. The church has had fewer more inglorious occasions than those when the Inquisition was active. Christians have gone on an orgy of excommunicating one another just because of disagreements about doctrine and liturgy, not to mention the downright obscurantism displayed in the persecution of the likes of Galileo and Copernicus for propounding intellectual views that were anathema to the church at the time.

Slavery is an abominable affront to the dignity of those who would be treated as if they were mere chattels. The trade in fellow human beings should have been recognized as completely contrary to the central tenets of Christianity about the unspeakable worth and preciousness of each human person. And yet Christians were some of the most zealous slave owners who opposed the efforts of emancipators such as William Wilberforce. The Civil War in the United States of America in part happened because of differences of opinion on the vexed question of slavery. Devout Christians saw no inconsistency between singing Christian hymns lustily and engaging in this demeaning trade in fellow humans. Indeed one of the leading hymn writers of the day was also an enthusiastic slave owner.

Religion should produce peace, reconciliation, tolerance, and respect for human rights but has often promoted the opposite conditions. Yet the potential for great good in the impact and influence of religion remains.

Christians have been foremost supporters of anti-semitism, blaming Jews for committing deicide in crucifying Jesus Christ. A devastating chapter in human history happened with Hitler’s final solution culminating in the Holocaust. Hitler purported to be a Christian and saw no contradiction between his Christianity and perpetrating one of history’s most dastardly campaigns. What is even more disturbing is that he was supported in this massive crime against humanity by a significant group called German Christians. Mercifully there were those like Dietrich Bonhoeffer and others who opposed this madness, often at great cost to themselves as members of the confessing church. Christianity has often been perversely used in other instances to justify the iniquity of racism. In the United States the rabid haters of blacks, the Ku Klux Klan, have not balked at using a flaming cross as their much feared symbol. One would have to travel far to find a more despicable example of blasphemy. Apartheid in South Africa was perpetrated not by pagans but by those who regarded themselves as devout Christians. Their opponents, even though known to be Christians, were usually vilified as Communists and worse. Many conflicts in the world have been started and certainly been made worse by religious and sectarian differences, as we see in many of the conflicts in Northern Ireland, in Sudan, in the Indian sub-continent, and in the Middle East. Religious differences have exacerbated the horrendous bloodletting in Bosnia euphemistically described as ethnic cleansing.

Religion should produce peace, reconciliation, tolerance, and respect for human rights but it has often promoted the opposite conditions. And yet the potential for great good in the impact and influence of religion remains. I can testify that our own struggle for justice, peace, and equity would have floundered badly had we not been inspired by our Christian faith and assured of the ultimate victory of goodness and truth, compassion and love against their ghastly counterparts. We want to promote freedom of religion as an indispensable part of any genuinely free society. ♦

Recommended Citation

Tutu, Desmond. “The First Word: To Be Human is to be Free.” Canopy Forum, December 26, 2021. https://canopyforum.org/2021/12/26/the-first-word-to-be-human-is-to-be-free/