Extremism, Dissent, or ‘Just a Job’? The Lethal Concoction of India’s Anti-Terror Laws and Media Policy in the Kashmir Valley

Annapurna Menon

Kashmir Valley in India by Kriti Kuhoo (CC BY-SA 4.0).

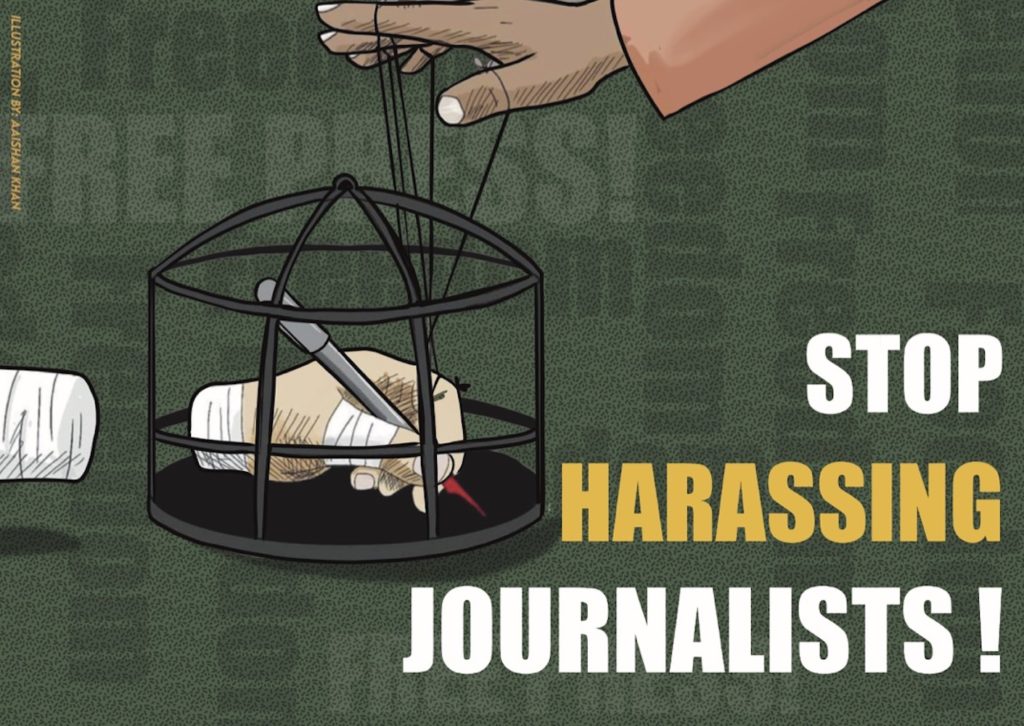

A prominent Kashmiri journalist, Fahad Shah has completed one year in prison, where he is being held under the draconian Public Safety Act (PSA) and the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). The charges against him are broad; they primarily accuse Shah’s work and magazine, The Kashmirwalla, of promoting “anti-national” narratives. Shah’s case is not unique. Several Kashmiri journalists have been languishing in prison on unproven charges under the PSA and the UAPA, laws that allow for preventive detention without trial for a period of two years. One of them, Aasif Sultan, has been in jail since 2018 and was recently granted bail, only to be immediately rearrested on another case. Even those not currently imprisoned live in a tightly controlled environment, and are subject to severe restrictions on publishing and travel.

In this article, I show how the Indian state is using a combination of anti-terror laws and the 2020 J&K Media Policy to criminalise Kashmiri journalists, all while using Islamophobic language to legitimise their actions. This legitimisation takes place both through state actors such as the police forces, who reiterate such language in their reports, and through media platforms, whose coverage seeks to make the majority Hindu population consent to these repressive actions. First, I will contextualise the current political environment in India, especially in relation to press freedoms and the disproportionate imprisonment of minorities in the country. This is followed by a brief introduction to the region of Kashmir and the implementation of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act (2019) and the J&K Media Policy (2020), which highlight the dehumanisation and dispossession of the people of the state in general, and Kashmiri Muslims in particular. I then return to the case of Fahad Shah, focusing on how the media’s (mis)representation of him as a radicalised youth, combined with India’s anti-terror laws, sets a dangerous precedent in the Kashmir valley. In the conclusion, I note the implications of this for people in both Kashmir and India while calling for an urgent repeal of the anti-terror laws and a serious rethinking of the state’s Media Policy.

India slipped 8 places in the RSF Press Freedom Index from 2021 to 2022; it is currently ranked as 150 out of 180 countries for freedom of press. When considered in light of the rise in persecution of religious minorities in India, the country’s criminalization of free speech is not surprising. The last four years saw some of the largest protests in the country in response to the discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the (eventually revoked) Farm Bills. The government of India made use of the Covid-19 pandemic to completely put an end to the anti-CAA protests, and continues to harass and penalize people who may have participated in the protests in any manner. The UAPA and the PSA have been heavily employed as a tool to punish those who were a part of the protests, and the available information already shows a very clear bias against minoritized people in the implementation of these laws. In addition, Muslims, Dalits and tribals are disproportionately represented in Indian jails, forming over 50% of the imprisoned population.

In Jammu & Kashmir, these statistics become even worse; these states have also been the site of long imprisonment periods without trial, specifically for Kashmiri Muslims. The situation has worsened after the revocation of the region’s limited autonomy, which had been progressively eroded over the years. In 2019, after the Bhartiya Janata Party (Indian People’s Party, or BJP) was re-elected, the Party set to fulfil their promises involving the revocation of the region’s “special status” in order to ensure the “integration of Kashmir into India,” despite the Indian state’s long-standing narrative that Kashmir was already an integral part of India. As part of this move, the J&K Reorganisation Act was introduced, which bifurcated the state into two parts. While this is not the space to go into depth on the implications of this Act, my PhD research noted how this Act is integral to the Indian state’s colonial domination over the region. It establishes a clear hierarchy between the Indian state and the people of J&K by creating and monopolising knowledge production over the “self” and “other” and by dehumanising, dispossessing, and depersonalising Kashmiri Muslims.

Here it is pertinent to note that the PSA and the UAPA have long been used to silence dissent in the region, even before the BJP came to power. However, under the BJP misuse of the two provisions has increased against Kashmiri Muslims and is now reminiscent of their use by the British Empire in India,. The government has also introduced several acts relating to media, land use, and citizenship that have a direct impact on people’s rights within the state. The Media Policy presents a disturbing case of creating such provisions to curtail any existing freedoms in the name of “national interest.”

In my PhD research, I provide a critical discourse analysis of the New Media Policy, and show how it represents the state’s objective of controlling media representation and providing tools that can be weaponized against dissenting individuals or platforms. The Policy document notes that “a fresh and proactive media policy is required to carry the message of welfare, development and progress to the people in an effective manner.” This is to be achieved by shifting the focus from print to digital media, focusing on radio and television as tools of disseminating information, and through promotional events such as media tours. Despite this, the Policy ignores the fact that internet shutdowns are the norm and internet speeds are often curtailed, disrupting the work of online media platforms.

The Policy clearly notes that it would not support media coverage in any format that “carr[ies] out any act or propagate[s] any information prejudicial to the sovereignty and integrity of India.” This not only means that dissemination of information is controlled, but that state bureaucrats now decide what should be covered and how. This is reflected in the following quote:

“The authorities must also satisfy themselves that the newspaper/magazine has not indulged in any unethical, anti-social or anti national activity or publication”

No definition of what qualifies as unethical, or anti-social or anti-national is provided, giving the state the power to frame the narrative exactly as it would suit them. Journalists have been a prime target of this media policy, especially local journalists who are now expected to undergo background checks.

The Policy, while dangerous for journalists and media professionals, aims to create a “sustained” narrative for the government. It is justified in the name of “national security”:

“J&K has significant law and order and security considerations. It has been fighting a proxy war supported and abetted from across the border. In such a situation, it is extremely important that the efforts of anti-social and anti-national elements to disturb the peace are thwarted.”

This rhetoric, which aims to convince the Indian population of the Policy’s necessity, is complimented by a vicious media narrative that is explicitly Islamophobic. This can be seen in the case of Fahad Shah. Co-founder of a local daily, The Kashmir Walla, Shah is also globally renowned as a journalist who has published for platforms such as TIME Magazine, the Christian Science Monitor and Foreign Policy. Shah was slapped with UAPA for his website’s coverage of a gunfight between the Indian military and militants, which asserted that the slain “militant” was in fact an innocent civilian. Later on, Shah and two other journalists who have previously contributed to Shah’s magazine saw the PSA used against them for encouraging “narrative terrorism.”

Apart from criminalising Shah’s journalism, the government also claimed that he had a “radical ideology from childhood” and was actively disseminating “anti-India sentiment,” “ISI propaganda,” and a “victimhood narrative.” The narrative established here plays on the normalised Islamophobia in India, and seeks to normalise the arbitrary detention of Kashmiri Muslims, who are associated with Pakistan and radicalised Muslims. This “othering” is done not just to silence dissent, but to create an atmosphere in which Kashmiri Muslims are maligned for their very identity, a criminalization made palatable to the majority population by the media. The Indian state has not restricted its application of these restrictions to native journalists; at the end of January, the central government activated emergency powers in the Information Technology Act to ban a BBC documentary questioning the role of Modi in the Gujarat Pogrom of 2002. This is only one example of the extent to which the government will go to protect its image, even if it comes at the cost of fundamental rights as guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. The international community must consider taking a proactive critical stand towards the world’s largest democracy in order to protect the credentials of democracy and rights of citizens, and take a stand against the inhumane and cruel detention of minoritized groups in the country.♦

Dr. Annapurna Menon is a Teaching Associate at the University of Sheffield. Her doctoral research focused on the coloniality of postcolonial nation-states, specifically studying the Indian nation-state’s exercise of power in Indian-administered Jammu & Kashmir.

Recommended Citation

Menon, Annapurna. “Extremism, Dissent, or ‘Just a Job’? The Lethal Concoction of India’s Anti-Terror Laws and Media Policy in the Kashmir Valley.” Canopy Forum, February 17, 2023. https://canopyforum.org/2023/02/17/extremism-dissent-or-just-a-job-the-lethal-concoction-of-indias-anti-terror-laws-and-media-policy-in-the-kashmir-valley/