Defining the True Meaning of Racism:

The Law & Religion of Colonial America

Part II

Audra L. Savage

“Slave Ship: Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On” by J.M.W. Turner 1840 / Wikimedia / PD

This article is part of our “Race, Religion, and Law” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

This is the the second installment of a three-part series that explores legal, religious, and racial dimensions of American slavery. Part I explored some of the reasons why white Europeans selected Africans, out of all racial and ethnic groups, for forced, unpaid labor. This part describes some of the ways Black people were used as tools to achieve the goals of white people. Part III will conclude with a description of the manner in which the personhood, humanity, and agency of Black people were ignored and denied.

The idea of racism is fraught with misunderstandings and misapplications. By exploring the twin institutions of law and religion in the 17th and 18th centuries, the true definition of racism surfaces. In the historical American context, racism is the use of Black people to achieve the goals of white people without respect to the personhood, humanity, and agency of Blacks.

For the (White) People

Blacks in colonial America served only one purpose: unpaid labor. In order to maximize profit, the British colonists would need a large supply of workers and as little overhead costs for that labor as possible. From this need, American slavery was born.

Black Bodies

For the use of cheap labor to be effective, there has to be control over the labor in order to maximize profit. Over time, it became apparent that the best way to control slave labor was to commoditize it by turning humans into property. Property can be evaluated, alienated, bartered, and managed in any way to the benefit of the owner. The ownership of a human being presented unique legal challenges―the first of which was defining which type of property to label the slave. For about fifty years after Black slavery became routine in the colonies in the 1600s, several colonies experimented with whether the slave should be freehold property (a form of real property, like land or buildings) or personalty (chattel property, like a horse or a wagon). It was clear by the mid-18th century, however, that southern jurisdictions had settled on the legal definition of slave as “chattel personal.” As chattel, the slave owned no rights to its mind, body, or soul. They existed merely for the work and pleasure of the master. They could be worked unto death, beaten, tortured, raped, sold, bequeathed, and bred. Once the law settled on the African as property, there were very few limits to what the law would not sanction.

Slaves planting sweet potatoes on James Hopkinson’s Plantation, circa 1862. Henry P. Moore / Wikimedia / PD

As the number of African slaves arriving in America grew exponentially (either directly from Africa or after being “seasoned” in the West Indies) in response to the growth of the nascent economy resulting from the slave labor, so too did the body of laws and customs regarding slavery grow. The colonies codified the various laws concerning the status of Blacks into slave codes. Although the laws may vary by colony, they all shared the same ultimate purpose: to control the commodity to ensure the continued means of operating the plantation to make money.

The slave codes covered all manner of daily life for the slave and created a regulated society between whites and Blacks. There was no aspect of life too mundane for the notice of the law. Slave codes governed the sexuality of slaves, especially if white lovers were involved; the ability of slaves to hire themselves out to third parties for wages; the ownership of horses, cattle, sheep, and crops; the ability of slaves to read or write; and the type of clothing slaves were allowed to wear. Laws also proscribed the participation of Blacks in the militia and military service, as well as the use of their testimonies in court. Of obvious importance was the need to prohibit a slave’s self-liberation by running away. The codes were explicit in detailing the punishments for attempted escape, as well as for inciting insurrections.

In short, the codes provided a blueprint for colonial society. They regulated the manner in which whites and slaves would conduct themselves, and they clearly delineated the status of the African person as slave and as property.

Another benefit of commoditizing Blacks as property was the ability to prevent poor, propertyless whites from aligning with slaves and free Blacks to rebel against the wealthy ruling class. Maintaining the hierarchy so that white indentured servants had more legal rights and higher status ensured the ruling class that their hegemony over society and wealth would not be challenged.

Black Souls

The law was not the only mechanism used by the gentry to control their capital investment, the slave. Religion was also complicit in controlling slaves. In the time leading up to the Revolution, the spiritual life of Africans and African-Americans furthered the goals of the white colonists in one of two ways. First, the established religions promoted the conversion of slaves to Christianity as a way of making Blacks better slaves, thus protecting the commercial ends of the planters. Second, including Blacks in Christian worship was a way for dissenters to agitate against the established religions.

Under established religions (e.g. Anglican, Puritan), the norms of the Christian community only applied to white members of the community. African slaves and their descendants were quasi-members, at best. While they were part of the community in terms of the application and enforcement of laws, they were never completely accepted as members of the religious community under established religion. Once the Africans arrived in colonial America and on the plantation, masters seemed unwilling to expose them to Christianity and were unconcerned with converting them, despite the many protestations of the clergy. A common belief among the planters was the baptism of slaves into the Christian faith would lead the slaves to disobey the laws and rules of the plantation, as well as lead them to join with other slaves to revolt against whites. Another fear of the planters explaining their indifference to proselytizing their slaves was the fear of losing racial superiority―the unconverted slave reinforced the white construction of Africans as the heathen other.

…the unconverted slave reinforced the white construction of Africans as the heathen other.

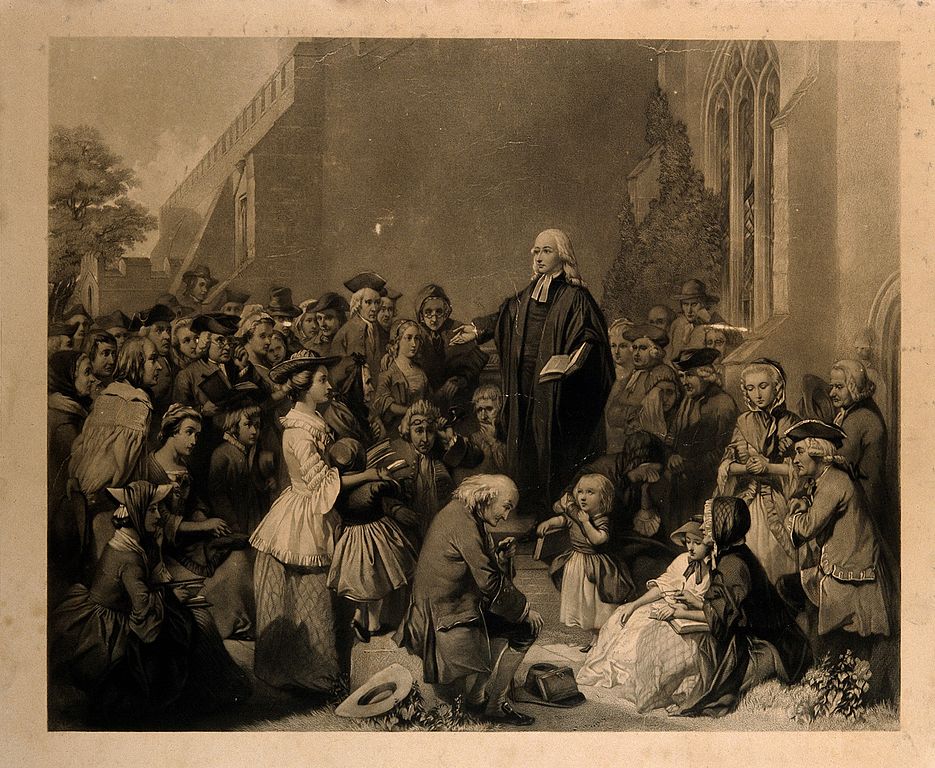

The entanglement of church with daily life belies the fact that the colonists were losing religious fervor over the course of the 18th century. Into this waning religiosity entered John Wesley in the mid-1730s and a new form of religion. Evangelical Christianity offered a new way of worship by replacing the staid, formal church service offered by the establishment with a new revival format. The Great Awakening revitalized Christian commitment. It presented a new world of spiritual possibilities. By the end of the Great Awakening (christened the “First Great Awakening”), there were new Protestant denominations, namely Methodist, Presbyterian, and Baptist faiths, vying for the affection of the colonists.

John Wesley preaching outside a church during the Great Awakening / Wikimedia CC BY 4.0

The itinerant preachers who crisscrossed the colonies and the people who followed them and listened to their messages were dissenters against the established religions. In addition to regaining spiritual guidance and commitment, the leaders of the Great Awakening distinguished themselves from the established religions by evangelizing to a group that had long been neglected by religion―Blacks. The revivals of the Great Awakening made religion attractive to slaves and free Blacks in a way not seen under established religions, with its use of oral tradition and emotional, vibrant worship style; its inclusion of slaves and the belief in the spiritual and intellectual capacities of Blacks; and a sense of equality amongst believers. Early on, Africans spurned the Church of England from the time of their arrival due to the adherence to their own religions, contempt for the beliefs of enslavers, and also linguistic barriers. The Great Awakening addressed these concerns.

The inclusion of Blacks provided added ammunition to the dissenters’ protest against established religion. Revivalists were able to turn the social hierarchy of the mid-to-late 18th century on its head and use it to dislodge the established religion. Dissenting revivalists were successful not because they challenged the role of slavery in society, but because they only challenged the role of slaves in worship. There was no real conflict between dissenters and Anglicans over slavery. Revivalists did not challenge or renounce slavery; in fact, some indirectly supported it (early on, some of the new denominations did support abolition; however, calls to end slavery were diminished as the denominations became more entrenched and established).

The leaders of the Great Awakening distinguished themselves from the established religions by evangelizing to a group that had long been neglected by religion―Blacks.

Under the Great Awakening, Blacks were included in the spiritual life of the community in a way that was lacking under established religion. However, this inclusion, while genuine, offered a powerful tool for religious dissenters to challenge the establishment and dislodge religion from the state. The egalitarianism that was promised was only meant to be spiritual―the revivalists were content to leave their brethren in chains. Once again, Blacks were used as a tool to promote the goals of white people.

Black bodies and Black souls advanced the needs and wants of white people during the time of American slavery. This fact is made more abhorrent by the wanton disregard for the personhood, humanity, or agency of Black people. This will be explored in the next installment.

Further Reading

Finkelman, Paul. “The Centrality of the Peculiar Institution in American Legal Development.” 68 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 1009 (1993).

Frey, Sylvia R., and Betty Wood. Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Higginbotham, A. Leon. In the Matter of Color: The Colonial Period. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Jordan, Winthrop D. White over Black: American Attitudes toward the Negro, 1550-1812. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Kidd, Thomas. “Protestant Evangelicalism in Eighteenth-Century America.” 1 The Cambridge History of Religions in America (Volume I: Pre-Columbian Times to 1790). Stephen J. Stein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Kidd, Thomas S. God of Liberty: A Religious History of the American Revolution. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

Wiecek, William M. “The Origins of the Law of Slavery in British North America.” 27 Cardozo L. Rev. 1711 (1996).

Audra L. Savage, SJD is Senior Lecturer and Postdoctoral Fellow at Emory University School of Law and the Center for the Study of Law and Religion, as well as a McDonald Distinguished Fellow. Her work examines the law’s effect on the rights of racial and religious minorities, engaging several different fields of study.

Recommended Citation

Savage, Audra L. “Defining the True Meaning of Racism: The Law & Religion of Colonial America – Part II.” Canopy Forum, March 25, 2020. https://canopyforum.org/2020/03/25/defining-the-true-meaning-of-racism-the-law-and-religion-of-colonial-america-part-2/