The Cross and the Criminal Record

Darrin Sims

Photo by Guido Coppa on Unsplash.

Though you might not know it, you’re probably familiar with the Biblical story of Barabbas. Appearing only briefly in the crucifixion narrative of the New Testament, Barabbas is the prisoner who was chosen by the crowd, over Jesus Christ, to be released by Pontius Pilate in a customary pardon before the feast of Passover. We have no record of Barabbas after his release back into society. We can speculate on his crime, which could have been anything from murder to petty theft. We can also note that his name may connote that he was the son of a prominent teacher or religious leader (“Bar Rabba”—”Son of the Teacher,” in Aramaic), and thus may provide some insight into his societal status. What we certainly know is that Barabbas was a convicted felon who had been released back into society.

For many readers, this is where Barabbas’s story ends. But as an ex-felon who has been released back into society, Barabbas shares an experience that many individuals who are returning citizens still face upon their exit from prison. Most often, upon their release, returning citizens meet an unforgiving society. Even after an individual has served their sentences, paid their fines, and completed their community service, their transition back into society is still faced with barriers—all because of their criminal record.

Criminal records, more commonly known as “rap sheets,” provide a complete history of a person’s arrestable offenses, or any offense that requires a fingerprint. Once something is in your criminal record, rarely can it be removed. Individuals with criminal records face challenges finding and maintaining employment, accessing safe adequate housing, participating in civic engagement, and a host of other things. “Returning to your community with a criminal record can be an uphill battle due to the collateral consequences of incarceration that limit access to employment, housing, healthcare and education,” said Sala Abdallah, Southern Coalition for Social Justice Community Organizer, and one-time offender. “Before leaving prison, I took a re-entry course, but I was given unreliable information that led to many disappointments upon my release. That experience inspired me to want to find ways to create a more positive release experience for others, and this toolkit is a good first step towards that goal.”

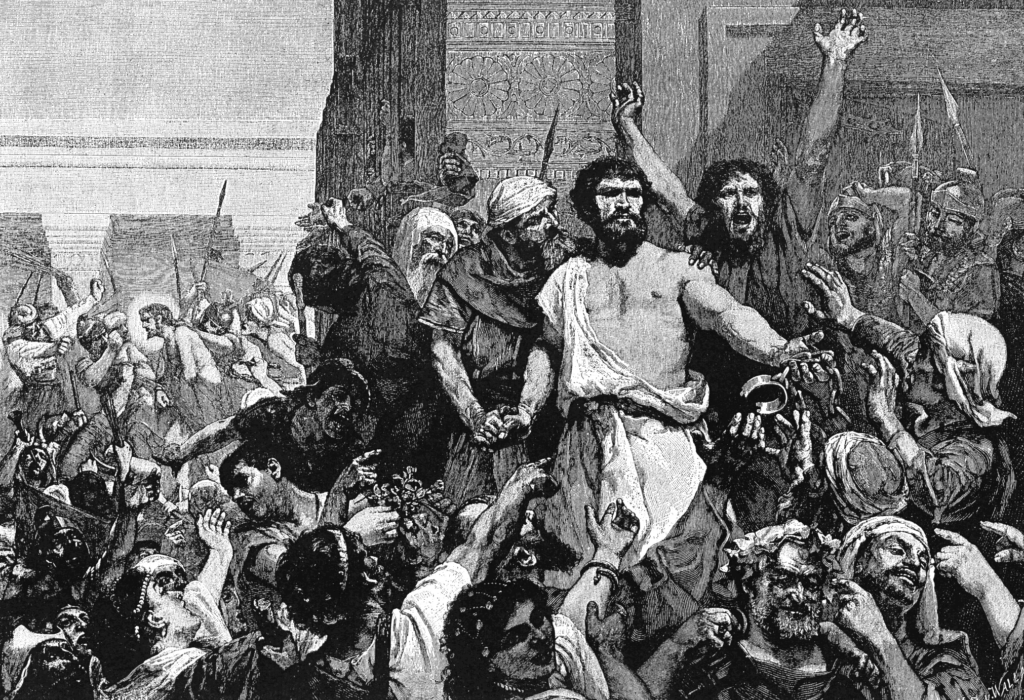

“Give us Barabbas!” from The Bible and Its Story Taught by One Thousand Picture Lessons. (PD-US).

Nationally, there are 48,000 laws that create economic and social obstacles for individuals re-entering society. Additionally, 86% of employers consider a person’s criminal record when making hiring decisions, making it difficult for formerly incarcerated individuals to obtain gainful employment.

Over 73 million people (about twice the population of California) — or one in three people in the U.S. — currently have a record of past criminal history, triggering numerous collateral consequences affecting access to education, employment and professional licenses, housing, social services and benefits, parental and adoption rights, freedom of movement, and voting rights. Given profound racial disparities at every stage of the criminal punishment system, Black people are disproportionately affected by these restrictions and exclusions. In total, there are over 10 million arrests each year, and 5 million people (about twice the population of Mississippi) are arrested and booked every year, with many multiple times each year. As a result, the US has one of the largest electronic criminal databases in the world.

Debate over whether criminal records should be considered public or personal information continues today. Some believe that the public has a right to know who is living and working in their communities. Many supporters of public criminal record access argue that it is important for individuals who have committed violent crimes to have their record made available for the protection of the community. Employers also must wrestle with the pros and cons of hiring people with criminal records. There is a widespread belief that hiring someone with a criminal record leads to more workplace criminal activity and lowers productivity among other employees. According to James Jacobs, author of The Eternal Criminal Record, citizens should have a right to know when individuals in their community or workplace represent a potential threat. But don’t former convicts deserve rights as well?

There is surely some truth to the argument that individuals with certain violent records, such as those who have committed crimes against children or seniors, should be excluded from working with those populations. However, as a society, we must begin to ask about the kinds of reckonings we have with individuals who possess a criminal record. What happens if communities, groups, and institutions can regulate who is able to be a part of their communities because of past actions? In fact, by excluding individuals with criminal records from living in certain neighborhoods, working alongside us, or attending our churches, we reinforce the notion that people with criminal records are not wanted in society—an exclusion that only encourages them to operate outside of society’s legal norms.

Criminal records and the barriers that they create stand in contradiction with the Christian faith. They invalidate the teachings of Christ and the embedded theology of sacrifice, redemption, and grace.

Many countries that pride themselves on being “Christian,” or at least as understanding the religious teachings of Christian doctrine, also prove to be some of the harshest places for individuals possessing a criminal record. It would seem that grace, forgiveness, and redemption, tenants of the Christian faith, fail to apply to individuals with criminal records. In many ways, criminal records are the new technological scarlet letter. They equate a person’s worth with the worst thing they have ever done, creating the moral stigma of a second-class citizen. Shame, guilt, and embarrassment are common feelings associated with having a criminal record. In this light, criminal records directly contradict the moral and religious teachings of the Christian faith.

In many cases when a person returns from prison, society tends to treat them like Barabbas. It’s often assumed that their story ends, and they can successfully integrate into society. It is easy to think that the chapter of their story is closed, and that they can proceed to live and effectively contribute to society in the ways that are meaningful to them. But in fact, their story and lives are just beginning again. Criminal records in many ways rewrite the life of the individuals who hold them. Just like the Christian cross the criminal record is symbolic and has a deeper meaning beyond its iconography. The rights and privileges that all of us are born with are unilaterally scripted away just because a person has committed a crime, regardless of the severity of the offense or even duration of the sentence. Criminal records and the barriers that they create stand in contradiction with the Christian faith. They invalidate the teachings of Christ and the embedded theology of sacrifice, redemption, and grace. Just like the Christian Cross the criminal record holds a symbolic meaning. While the cross represents suffering, sacrifice and redemption, criminal records tend to represent the complete opposite. They reflect disapproval, immorality and the human desire to hold a grudge.

How can people of faith remedy the harmful theology that creates second-class citizens? However, there is a growing movement to restrict, expunge, or seal criminal records, depending on the specific circumstances and laws in that state. Supporters of this movement to allow individuals to make their criminal records less accessible to employers and other agencies argue that these individuals deserve a second chance. Jacobs contends how the records of convicted persons who go years without a new conviction should be expunged or restricted. He further proposes strategies for eliminating discrimination based on criminal history. Such strategies include restricting the records of those who have demonstrated their rehabilitation. Record expungement and restriction are deeply rooted in Christian ideals and have gained support amongst faith communities throughout the county. Faith communities in many cities have galvanized support for legislation that supports second chance bills which would make it easier for criminal expungement.

The concept of second chances absolutely must be paired with justice, and we are reminded of that not only by criminal expungement advocates but also by scripture and the life of Jesus.

On top of that, the financial stability, structure, and social networks gained from employment help people with a record reduce their likelihood of re-offending, increasing the safety and prosperity of all within the community. Studies have shown that steady employment leads to a 62% reduction in recidivism among individuals with a record. Fewer than 2% of people are re-convicted within five years of clearing their records. A cleared record increases likelihood of employment by 11% and wages by 22% within the first year. Record expungement leads to an average increase of $6,190 in yearly income per individual.

In Georgia, these figures were the cause behind recent SB 288 law, known as the Second Chance Bill, that recently went into effect January 1st, 2021.This bill had bipartisan support, as well as the support of faith communities, and aims to provide for restriction and sealing of certain misdemeanor convictions from an individual’s official Georgia criminal history. Individuals must have remained crime-free for 4 years, no matter how old they were when the conviction occurred.

This bill and others around the county speak to the deep theological concepts that should be embedded in the justice system. It is our duty as actors and participants within the criminal justice system to help restore the humanity of systems that affect real people. The concept of second chances absolutely must be paired with justice, and we are reminded of that not only by criminal expungement advocates but also by scripture and the life of Jesus. ♦

Additional Resources:

“‘Second Chance’ Law Takes Effect, Offers Hope To Georgians With Criminal Past” | Georgia Public Broadcasting

“Mass Incarceration, Visualized” | The Atlantic

“‘The Secret Life Sentence of Being a Felon’ by Harley Blakeman” | TEDx Talks

Darrin (DJ) Sims is a minister, teacher and organizer in Atlanta, GA. He currently is a 3rd year Master of Divinity Student at Candler School of Theology at Emory University.

Recommended Citation

Sims, Darrin. “The Cross and the Criminal Record” Canopy Forum, January 26, 2021, https://canopyforum.org/2021/01/26/the-cross-and-the-criminal-record/.