Religion, Insurrection, and Social Forgiveness

Joseph Margulies

Photo by Wesley Tingey on Unsplash.

This article is part of our “Chaos at the Capitol: Law and Religion Perspectives on Democracy’s Dark Day” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

In a deeply divided nation, and especially after the events of January 6, 2021, no one is in a particularly forgiving mood. But times like these are precisely when we should make forgiveness part of our conversation.

Luke 23:34 offers a simple admonition: “Then Jesus said, ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.’” (Luke 23:34, KJV). Yet like many scriptural passages, this verse makes less and less sense the more you think about it. The setting is clear enough. It is Jesus’s penultimate prayer. Pilate has acceded shamefully to the demands of the crowd to crucify Jesus, though he has done no wrong. As Jesus hangs on the cross, rulers scoff at him (“He saved others; let him save himself, if he is the Christ of God, his Chosen One!”), soldiers offer him sour wine and mock him (“If you are the King of the Jews, save yourself!”), and those in attendance “cast lots to divide his garments.” But through it all, Jesus remains magnanimous, imploring the Lord to forgive them, “for they know not what they do.”

Wait, what?

To withhold forgiveness from those who commit grave injury seems perfectly normal. One thinks of The Sunflower, Simon Wiesenthal’s hauntingly poignant account of the member of the SS who, on his deathbed, begged Wiesenthal, as a Jew, to forgive him for the many crimes he had committed against countless other Jews. Wiesenthal demurred, denying the man his dying wish. Philosophers and theologians have debated for years about Wiesenthal’s refusal, but few fail to recognize the impulse to be unforgiving.

Still, rare as it may be, forgiveness in the face of unspeakable wrong is hardly unprecedented. After Dylan Roof murdered 12 worshippers who had welcomed him into the Emanuel AME church in Charleston, South Carolina, many of their grieving relatives forgave him. “I forgive you,” said Nadine Collier, the daughter of 70-year-old Ethel Lance. “You took something very precious from me. I will never talk to her again. I will never, ever hold her again. But I forgive you. And have mercy on your soul.” Similar proclamations are widely available — consider, for instance, the teachings of Archbishop Desmond Tutu or the efforts of the London-based Forgiveness Project.

What makes Luke 23:34 inexplicable is not Jesus’ determination that his tormentors be forgiven, but that he should direct his plea to the Lord: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” But what could possibly be the point of reminding God that people act in ignorance? Surely He knows that. In fact, I would venture He is the only one for whom the admonition is superfluous. And why would Jesus need to beseech God to forgive ignorant transgressors? I had never thought God needed to be reminded of His role.

In fact, the only way to make sense of the passage is to read it not as a plea to the Lord but to each other. At the simplest level, the passage implores us to forgive those who act in a state of ignorance. Yet if that were all we got from Luke 23:34 it would be little more than a bumper sticker. The more profound message in the text is that we are ignorant even of our own actions — even, and perhaps especially, when we believe we know full well what we’re doing.

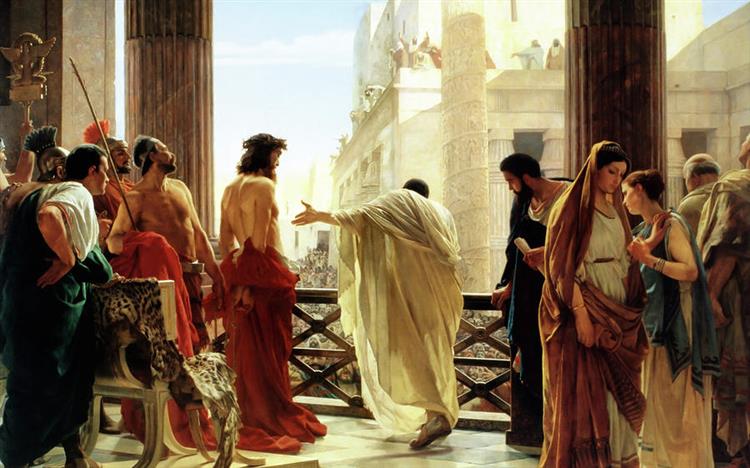

“Ecce Homo” by Antonio Ciseri, 1871. (PD-US).

The prefect who ordered that Jesus be crucified, the crowd that cheered his execution, the soldiers who provided official protection and the gamblers who divided his clothes: according to Jesus, they all “know not what they do.” Yet if we had asked them, I suspect they would have said they knew exactly “what they do.” But Jesus tells us they delude themselves. This is key to understanding the passage: the perception of our own moral certainty is a delusion. Moreover, Jesus draws no distinction among them; they occupy different positions in the social hierarchy and act in different ways, but all are equally ignorant. This diversity — from the prefect to the gambler, from the common spectator to the palace guard — suggests that everyone is ignorant of their own actions, which of course includes those who might be inclined to judge others.

Now we are getting somewhere. Luke 23:34 is a radical proclamation that we are all equal in our ignorance. But ignorant of what? Here I think the answer is that we are ignorant of how we would act if the shoe were on the other foot. If I were Pilate, would I ignore the imprecations of the crowd? If I were destitute, would I resist the temptation to steal clothes? If I were a soldier, would I disobey an unjust order? If I am honest with myself, the answer is that I don’t know. But since I do not believe I am any different from the great mass of humanity, my strong suspicion is that I would succumb, especially if I lived as they had lived and experienced all they had endured. A reader may protest and insist they are not capable of great violence against another human being. Unfortunately, the lessons of history and psychology are not kind to this conceit. This is what Nietzsche had in mind when he warned against hubris:

The fact that one has or has not had certain profoundly moving impressions and insights into things — for example, an unjustly executed, slain or martyred father, a faithless wife, a shattering, serious accident — is the factor upon which the excitation of our passions to white heat principally depends, as well as the course of our whole lives. No one knows to what lengths circumstances … may lead him. He does not know the full extent of his own susceptibility. [A] wretched environment makes him wretched.

What is true of individual violence is even more true for collective violence, or the injury inflicted by members of a group on real or imagined outsiders. “Ordinary” people regularly inflict great suffering on those outside their magic circle. To them, the violence is morally justified. Worse, the research suggests that violence in defense of one’s tribe produces a demonic cycle: the attachment to the group motivates violence in its defense; in turn, the violence intensifies the attachment. All of this may seem utterly irrational, but as the political theorist William Connolly reminds us, every villainous act is incomprehensible to those who judge it from the outside, yet entirely sensible to those who see the world through the villain’s eyes.

And since January 6, all of us think we can see plenty of villains.

What do we know of the men and women who sacked the Capitol? We identify them by their full-throated allegiance to the President, their unblinking certainty that the election was “stolen,” and their resolute conviction that the country they love is in peril. But what do we know of them as individuals? Not as part of a lawless mob that converged on Washington in response to the President’s reckless call and erupted in a paroxysm of violence, but as distinct people? If we are honest, we will admit that we know next to nothing about them. Nothing of the terrors that haunt them at night or the joys that give them solace. Nothing of the fear they have for the child who lies ill or the parent who slips away. We do not know what makes them laugh or cry. We do not know their heart.

We think we know them, but mostly we’re just conjuring mental images based on snippets of information that we fold into a pot of myth and stereotype. In an article entitled “These Are The Rioters Who Stormed the Capitol,” two journalists with The New York Times introduce us to “Aaron,” a 40-year-old construction worker from Akron who declined to give his last name. (“I’m not that dumb,” he explained.) Once inside the Capitol, Aaron and two unnamed friends wanted “to have a few words” with New York Senator Chuck Schumer. “He’s probably the most corrupt guy up here. You don’t hear too much about him. But he’s slimy. You can just see it.” Alas, they couldn’t find his office, even after receiving directions from a helpful Capitol Police Officer. So they settled for smoking a few cigarettes inside the building. That’s what we know about Aaron, who emerges as barely more than a stick figure. Nearly all that makes him human is unknown; all that makes him part of society is a blank slate.

Even coverage that aims for nuance produces barely more than a caricature. Ben Smith, the astute media reporter for The Times, wrote a piece about Anthime Gionet, who livestreamed his assault on the Capitol January 6. The two had previously worked at BuzzFeed, where Gionet developed a talent for creating online content. Though Smith did not know him well, he interviewed some of Gionet’s former colleagues, “who recalled him with a mixture of perplexity and repulsion.” They described him as “sensitive and almost desperate to be liked.” Two of Gionet’s “closest friends” at BuzzFeed (though how Smith knows they were his closest friends is unclear since Smith did not interview Gionet) “had different ethnic backgrounds and gender identities than he did, and they sometimes bonded over a sense of being outsiders.” One of them described him as “sad,” and “haunted by a lonely childhood in Alaska.” Other coworkers speculated that Gionet was seduced by the thrill of social media, allowing the adulation of strangers to fill an otherwise empty personality.

The suggestion that we would condemn a person without first trying to understand them as flawed and complex humans (like the rest of us) is appalling.

Can we now say we know Gionet? Even Smith makes no such claim. He didn’t interview his subject, and candidly admitted he doesn’t care what Gionet believes (an astonishing admission for a journalist). And because we know almost nothing about Aaron, Anthime, or any of the men and women who stormed the Capitol, how can we presume any of them are beyond forgiveness? The suggestion that we would condemn a person without first trying to understand them as flawed and complex humans (like the rest of us) is appalling. Absorbing what I take to be the lesson of Luke 23:34, if we judge in ignorance, we risk acting in grievous error.

Of course, you may complain that I am imagining a personal narrative for the rioters out of whole cloth. True enough. But do you know anyone who does not have a story behind them? To ask the question is to answer it. We may not know what their story is, but we know they have one simply by virtue of being human. To deny this — to pretend they have no history — is to imagine they are other than human; it is literally dehumanizing.

Many balk at the idea of forgiving one of the insurrectionists because they think it will bring well-deserved punishment to a premature end — or worse, that it will preclude punishment altogether. But this misunderstands what society does when it forgives. When society forgives, it extends an invitation to someone who has transgressed to rejoin the group as a full member. Social forgiveness thus facilitates a return to normalcy by conditioning us to see that exclusion is an aberration. And because membership in a democracy is the norm, it must never be withheld arbitrarily or gratuitously, and ostracism or exile based on impermissible grounds is wholly indefensible. Thus, by restoring full membership, social forgiveness also brings unjust exile to a merciful end.

Because membership is the norm, the goal of the justice system should be to restore membership as soon as reasonably possible. To do that, we must build institutions and practices that will allow this restoration to take place, safely and harmoniously. It is beyond the scope of this short essay to describe the form of these institutions and practices, but for now it is enough to stress that they will not end punishment; they will begin the process of social forgiveness.

I cannot close this essay without addressing one charge against social forgiveness in this particular moment. Some will argue that it is simply a vacuous liberal shibboleth, selectively invoked to protect White supremacists with no realistic expectation that people of color would ever enjoy comparable protection. When the shoe is on the other foot, White supremacists will be as vengeful and vindictive as ever, and the unholy pairing of retributivism and racism all but guarantees an embrace of double-standards. If we forgive the insurrectionists, there is no remote chance that they will be forgiving of Black and Brown people.

The more profound message in the text is that we are ignorant even of our own actions — even, and perhaps especially, when we believe we know full well what we’re doing.

I accept the power of this critique. Long years as a criminal defense and civil rights lawyer have rid me of any temptation to be Pollyannaish. But I stick to my position. For one thing, I refuse to trade in dehumanization; it is a Rubicon I will not cross. It does not matter that others cross it with glee. I have spent my entire career standing with the people that many call monsters. I know what dehumanization does — not just to the poor souls cast beyond the pale, but to the self-anointed patriots who remain inside the magic circle, scrubbed clean by the blood of those they purge. I want no part of it.

More pragmatically, it is wrong to think that liberal institutions never bind themselves. The fragile, tentative embrace of criminal justice reform that has besotted the political class in the 21st century, like the corresponding embrace of civil rights two generations ago, shows us that a liberal regime is sometimes willing to sand down its roughest edges. Institutionalizing a commitment to forgiveness will never be applied perfectly, but like other reforms that have targeted the abuses of the carceral state, it can bring a measure of justice to those who would otherwise have none. The master’s tools may not dismantle the master’s house, but they can open a window that brings in much-needed light.

Many people ask me why society should forgive. I ask why society should be unforgiving. Why should it build institutions that ignore the complexity of human existence? Why should it design policies which deny the reality that people change, repent, and regret? The answer is it should not. If we are to integrate Luke 23:34 into daily life, we must come up with a way to accept that we cannot judge the wrongful acts of another until we labor to understand as best we can the path the wrongdoer has traveled. More importantly, we must withhold judgment until the attempt has been made. That is why society can forgive the insurrectionists, as we can forgive each other, and as Jesus would have it. ♦

Joseph Margulies is a civil rights and criminal defense lawyer, as well as a Professor of the Practice of Law and Government at Cornell University. For decades, he has represented people that others call monsters, including prisoners on death row and at Guantanamo, and feels certain he has never met a monster in his life.

Recommended Citation

Margulies, Joseph. “Religion, Insurrection, and Social Forgiveness.” Canopy Forum, January 22, 2021. https://canopyforum.org/2021/01/22/religion-insurrection-and-social-forgiveness/