Beekeeping on the Sussex Downs:

Philip Reynolds Reflects on Retirement, Happiness, and Echo Chambers

Photo by Tom Hoppe on Unsplash.

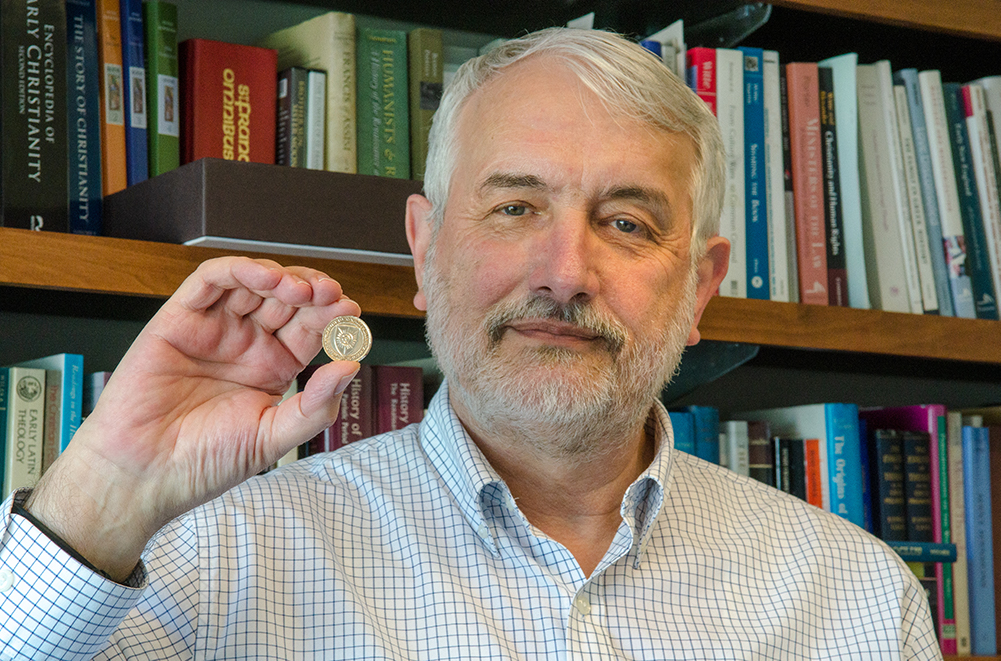

In the Fall of 2021, Dr. Philip L. Reynolds – a Senior Fellow at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Medieval Christianity, and Aquinas Professor of Historical Theology at Candler School of Theology – retired. For almost four decades, Reynolds has taught and published extensively in the field of historical theology, including his recent edited volume, Great Christian Jurists and Legal Collections in the First Millennium (Cambridge, 2019). He also served as the Director of CSLR’s Pursuit of Happiness project from 2005-2010; and, in 2019, he won the distinguished Haskins Medal in recognition of his monumental book, How Marriage Became One of the Sacraments (Cambridge, 2016).

CSLR recently asked Dr. Reynolds to reflect on his career and life as a scholar. What led him to the field of historical theology? What did he learn along the way? What advice does he have for scholars who are at the early stages of their careers? Reynolds – who plans to devote his retirement to writing, gardening, and exploring rural landscapes in his native England – responded with characteristic insight, erudition, and wit.

CSLR: You have been a member of Emory’s faculty since 1992, and prior to that served as the Downside Fellow at the University of Bristol in England. What are some of the highlights your time and work in these roles?

Philip Reynolds: From my Bristol days, I most value associations with such Catholic colleagues as the university philosophers Christopher Williams and Denys Turner (the latter is my daughter Isabel’s Godfather), and the monk-historian Dom Daniel Reese of Downside Abbey (who baptized Isabel). As for Emory, my participating in some of the CSLR’s major interdisciplinary projects has been the highlight. I have often described these projects, without any implied denigration of my own school, as “the most university-like” activities of my time at Emory. The opportunity to learn from professors in other fields, and to acquire skills in critical conversation with experts in just about any field of academe, was hugely valuable. Above all, though, this experience was sheer intellectual and collegial pleasure. Sometimes I’d withdraw for a few moments from the conversation and reflect that to be here, engaged in this, was a rare privilege and an unanticipated blessing.

At what point in your life or education did you decide to become a scholar of historical theology, and did you ever consider a different career path? Which aspects of your vocation – teaching, research, lecturing, etc. – have been most rewarding?

I was a very late developer, proceeding rather like boat with a broken rudder after I completed my BA in Philosophy and Psychology at Oxford, and eventually working on farm, but forever searching for something. (Avenues that seemed promising at that time included organic gardening, William Morris, and Buddhism.)

But by the late 1970s, I was beginning to find a home in Catholicism (especially monastic Catholicism), and during that period I was baptized and confirmed and received first communion from two monks on a single occasion in a small chapel in the crypt of Ampleforth Abbey. At the same time, I began to discover medieval monastic and scholastic writing, and I was drawn to it and felt at home with it. Fortunately, I had been forced to study Latin at old-fashioned boys’ schools from the ages of six through fifteen, and although I had hated it, I found now that I still had enough Latin to get me started as a medievalist. This new interest led me, rather late in life, to study for my PhD in Toronto, with priest-professors from the then-thriving Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies as my mentors.

As a scholar of historical theology, you have focused especially on studying the Christian tradition in the central Middle Ages. What might Christians from that period be surprised to learn about Christianity as it is practiced and believed today, and what might Christians today be surprised to learn about Christianity as it was practiced and believed in the central Middle ages?

That’s a hard question for me to answer. I would not call myself a theologian of any species; perhaps I am more an historian of theology; but this is not just history for me. I have become increasingly preoccupied with the vast differences between, on the one hand, the intellectual and cultural contexts and preconceptions of medieval thought, and, on the other hand, those of today. I don’t think this gulf can be bridged. Nevertheless, the scholastic thought and monastic culture of the Middle Ages remain iconic for me, in the way that some adopt individual thinkers or leaders from the past as personal heroes.

I confess that in moments of doubt I wonder whether my spending so much time and effort thinking about how people used to think is somewhat eccentric. But I am sure that modernity makes no sense. Contrariwise, just about every survivor of ancient religious cultures, including the episcopal and monastic institutions of Catholicism, have turned out to be apples with worms in them, if not vipers. I think that people who regard early or medieval Christian theology as something that can be brushed off and re-appropriated or recovered in any shape are kidding themselves and failing to grasp the challenges of modernity. So, I do not find such modern thinkers to be more “relevant” than I am. In our strange era, it seems to me, the only sane vocation is to be a restless spirit.

You have written or edited five major books since 1994, including How Marriage Became One of the Sacraments, for which you received the prestigious Haskins Medal from the Medieval Academy of America. What is that book about, and why did you write it?

Before the twelfth century, marriage was accepted as an honorable estate in the church, with features that might be characterized as “sacramental” in some sense, but no one considered marriage — or, more precisely, marrying — to be “one of the sacraments”. Indeed, the sacramental system itself, with its list of seven sacraments, was a twelfth-century development. The inclusion of marriage among those seven raised enough problems to keep scholastic theologians busy for a couple of centuries, but canon lawyers pretty much ignored their work, and the doctrine was not defined as dogma until the Council of Trent.

The development had less to do with helping married folk to understand their way of life than with articulating the rightful, if modest, place of marriage in the Christian hierarchy, at a time when the sexual orientation of celibacy was segregating the clergy and the friars as well as monks and nuns as élite Christian castes.

That’s the story of the book, which I wrote as my belated contribution to the CSLR’s Sex, Marriage, and Family project, with much encouragement (and, when needed, pushing) from my esteemed colleague John Witte. But I had no idea that the project would grow to be so big or take so long. It’s often said that Atlanta grows indefinitely because it has no natural boundaries, and much the same proved to be true of that book; or rather, the first natural boundary proved to be Trent in the 16th century, whereas I had set out to write a book that would end in the fourteenth century. There is a legal argument running through the book, pertaining to theology and not to canon law, but the book is so vast and detailed that this theme is a forest that can’t easily be seen for the trees, and I doubt whether anyone notices it!

From 2005 to 2010 you directed CSLR’s “Pursuit of Happiness Project,” which explored the meanings and implications of “happiness” from the perspective of multiple religious traditions. What was one of the main insights or lessons you took away from that project?

Unlike some of my colleagues on the project (such as my esteemed fellow-traveler Tim Jackson), I accept that some form of eudemonism must be the basis of any adequate Christian ethics, although I entertain at the same time a fondness for the philosopher Nicholas White’s skeptical claim in A Brief History of Happiness (which I encouraged my colleagues on the project to read, albeit without much success!). This is, roughly, that all forms of eudemonism — whereby eudaimonia, or “happiness”, is posited as the ultimate end of all human action — result from the fallacy of trying to reduce the many irreducibly disparate things that we pursue in life, from cuisine to justice, from symphonies to medical research, to just one thing.

Unlike Julia Annas, another colleague on that project, I find the English term “happiness” to be a hopelessly problematic translation of the Greek “eudaimonia” or of the scholastic “beatitude” and “felicity”. It’s too tied to ideas of mood and feeling. At the same time, we can’t leave life-satisfaction, pleasure, and emotional well-being out of the picture entirely. (We are vastly more aware of mood disorders today than our forebears were.) I want to have my cake and eat it here, and I find the solution, or convergence, in the religious, eschatological dimensions of well-being. That’s what I took away from the project. I wrote up my conclusions at the time in a little article for the Huffington Post, which I think has stood the test of time (the title is misleading, but it’s theirs, not mine).

As you approach your retirement, what are you most looking forward to? Do you have any advice for students and scholars in your field who are early in their careers?

Sometimes, just for fun, I think of my retirement as “beekeeping on the Sussex Downs” (Sherlock Holmes fans will understand the reference), although in fact I am returning to the Yorkshire moors, where I plan to continue writing and researching while recovering some hobbies that I relinquished around 1980, especially cultivating organic vegetables. Like Dr. Leana Wen, I recognize that my life and career have been overly shadowed by my being a covert stammerer, so I want to get involved again in the PWS (People Who Stammer) movement, as I used to be in the 1980s.

Above all, I love tramping over the Yorkshire hills and dales and visiting the remains of medieval monasteries and churches, which I have been doing every summer until Covid, so I hope to be doing plenty of that. While avoiding mega-conferences, which I have never enjoyed, I hope to keep open connections that will get me included in small, focused, workshop ventures, such as one in Rome to which I have been invited for May, 2022.

I am saddened to see first-class doctoral graduates here not getting academic positions anywhere. But I think I retired at the right time, quite aside from my age and my yearning for the Pennines of Yorkshire. The academic world, especially in the humanities and in religious and theological studies, is changing in ways that I rather think would have made academic life very difficult for me. Roughly, a traditional set of scholarly humanistic goals that used to be unquestioned in academe is being replaced by advocacy, where the goals are more moral than scientific. A balance has shifted, and the measure of excellence is becoming less about what truths one can discover and what explanatory insights one can shed and more about whether one can tell a story that people want to hear and that will uplift them, or that will satisfy and fuel their righteous indignation. It’s an echo chamber of sorts, albeit one predicated on high moral principles and deep social concern. I don’t belong in even a highly principled echo chamber.

Philip Reynolds

August 29, 2021

To learn more about Philip Reynolds’ career and scholarship, read the tribute published by Candler School of Theology, “Philip Lyndon Reynolds: Making Old Things New.”