Desmond Tutu and the Intersections Between Law and Religion

Toyin Falola

Ubuntu: I am because you are, because we are. But beyond that, I am because I belong, and I have chosen to belong, to form a part of, participate in, and unite with others and their ideas and ideologies, despite the realistic existence of nuances and differences. The meaning of this word reflects perhaps the strongest lesson we learned in the year 2020. Some might think it has become cliché to trace the challenges we face in our present day reality back to the year 2020. But then, 2020 was largely unprecedented, and until we fully stretch the elastics of discourse around this year and the new realities, revelations, and awakenings that came with it, then our conversation will continue to revolve around it.

The year 2020 taught us to embrace Ubuntu more than ever before: to be humans first and unite first; to recognize that Mmatsie, Serges, and Edith exist only because the human entity exists. This message was amplified in 2020. But before then, some people were already living by its principles. These people saw it as their culture, their philosophy of life. As a matter of fact, some propounded the theology and championed it. The most remarkable of them? Reverend Desmond Mpilo Tutu! May God rest his soul.

Rules Exist to be Broken

From time immemorial, it has been human nature to step out of line. Society has always known and will always know disorder at varying degrees, depending on the factors at play. Law and religion are as old as this disorder itself. They have been integral parts of human society – mechanisms for maintaining order. It is human nature to step out of line, but law and religion show us that it is also human nature to seek redress. Because we fall sick, we develop drugs and healing processes. When viruses infect our computers, we make antiviruses to protect the system. We might have a tendency to destroy, but we also have a tendency to devise solutions. Law and religion, then, are ever-evolving solutions to chaos and disorder.

The intersection between law and religion is a thick one, especially since religion was not always strictly private. Centuries ago, religion was an integral aspect of the state, so much so that religious leaders sat in the innermost circles of world emperors. Religion has established its position as an effective mechanism for maintaining order. It speaks directly to the ego ideal, strikes the conscience, and inspires people to do what is right. As long as morality remains a part of human society, so will religion. Although there are thousands of religions in the world, each with its differing views, they all have a common denominator: establishing the difference between right and wrong and guiding adherents away from choosing the wrong path.

In the secular sphere, the law serves as the common denominator for everyone. A lawless state would soon become a non-existent state, as everyone would be free to act as they please, thus leading to anarchy. The law is not without bias, and is in need of constant reform; however the law plays a crucial role in putting societies in check.

Just as religion teaches the difference between right and wrong, so too does the law. To do wrong is to sin, and with sin comes punishment. Such punishment comes in various forms and degrees, especially when handed down by the law, and even more so when a religion has informed the decision of that law. Over the centuries, the world has witnessed outrageous and overly harsh punishments meted out to lawbreakers, and in hindsight, we might be surprised to see that religious adherents and leaders have championed the severity of these punishments. But it should not be so surprising, as such punishments are earthly manifestations of their extremist religious doctrines.

As states have become secular, many countries have learned to distinguish between law and religion, reducing the severity of punishment. Yet some moral actors, forward thinkers, and seekers of justice can be found at the intersection of both law and religion. These individuals are not being manipulative or vindictive by allowing religion to unfairly influence the law; rather, they are harnessing the influence given to them by their religious position to ensure that laws are adhered to and that people consider the morality of their actions. Of course, there are extremists – terrorist groups, to give one example, or the forceful authoritarian regimes of religious nationalism. But there are also people like the late Reverend Desmond Tutu, who saw his religious position as a unique privilege to maintain the law and help fight for the rights of others.

Remembering Desmond Tutu

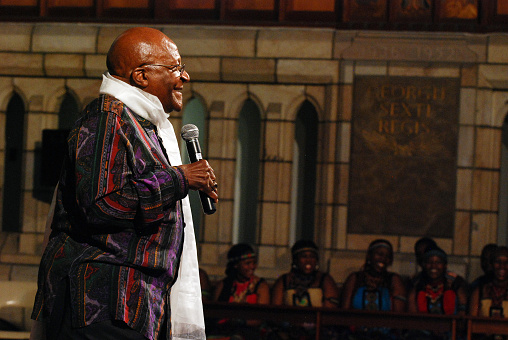

Desmond Tutu, the South African Anglican reverend, champion of the communalistic humanist cause of Ubuntu, and lover of peace and unity, took his last breath on December 26, 2021. He went to rest on a Sunday, the God-ordained day of rest. While we mourn the loss of a colossus, a core part in the armor of truthful humanism, we cannot but reminisce, in gratitude, on a life well-spent and impactful. I met the great man on several occasions: in Cambridge in 1988, where we had dinner as part of a group of admirers; in London; and then in South Africa, as a member of another group of people appealing to him to speak with the South African President to end xenophobia. He even gave me his personal phone number, but I did not call him once. When I wrote a tribute in honor of Nelson Mandela, he sent a message that I left out some names.

Tutu was a South African Anglican archbishop, a true humanist, and a firm believer in communalistic humanism. He was born in Klerksdorp, South Africa, on October 7, 1931. The circumstances surrounding his birth did not boast of financial buoyancy in the least; yet, Desmond was destined to be great and influential. Between 1931 and 1960, when he became a priest of the Anglican Church, he went through a series of training and development. The training would later form the basis of his faith, beliefs, philosophy, and culture.

Tutu was born and raised in South Africa when the apartheid system was thriving. Of course, a part of the country was seeing progress and advancement. However, a large part of the country, particularly the area inhabited by Black people, the true owners of the land, knew little to no progress, and the people were subjected to severe oppression. Desmond Tutu was well aware that he got his training and education swaddled in costly privilege, which came at the expense of several thousand other children. He was one of the beneficiaries of a grossly unjust system, and he never forgot that. Therefore, when that privilege provided him with a most-prized education and empowered him in 1960 when he joined the league of some of the most powerful people in South Africa — the priests — Desmond Tutu knew it was time to use what he had gained for the good of his people. And that was what he did. He fought relentlessly against the apartheid government of South Africa.

Here was a man who was brave to the core. A man who knew the circumstances surrounding how he came to possess the power he had begun to wield. A man who knew the rarity of the privilege he got, the wickedness of the system that operated in his country, and the overbearing likelihood of losing all that came into his possession if he pursued the much-despised path of fighting for the freedom of the South African people. But did that dissuade Tutu? Far from it. Rather, it strengthened him and pushed him to go further. It encouraged him to persevere against all odds and in the face of persecution.

The people were angry and fed up, and Tutu knew that humans are naturally inclined to be violent in such a state of mind, especially when it involves a high level of depravity on their soil. But he knew yet another thing — that violence hardly ever solves the problem, and that in those rare instances where it does, it causes bigger damage.

Desmond Tutu made the most of what he had — his voice, faith, position, and influence. He was a man with a mission, and he had a clear understanding of his goals. The archbishop was at the forefront of pulling in national and international commentators on the deeds of the apartheid government in South Africa. Although the South African people passed through what would go down as one of their worst times in history, Tutu preached the importance of making grievances known in a peaceful and non-violent way. The people were angry and fed up, and Tutu knew that humans are naturally inclined to be violent in such a state of mind, especially when it involves a high level of depravity on their soil. But he knew yet another thing — that violence hardly ever solves the problem, and that in those rare instances where it does, it causes bigger damage. The Bishop was not a man of violence. He demonstrated an exceptional devotion to peace by keeping the Nationalist Party in check when they became violent in their ways and dealings.

During the last decade of the last millennium, when his people finally won their battle against oppression and the apartheid government, Tutu was there to celebrate with his people. There was also the factional disagreement that threatened the embryonic freedom that the South African people had just got. And who else but the Very Reverend Demond Tutu, preacher and practitioner of the Ubuntu theology, stepped in at this critical moment? He persuaded both warring parties that each party is because the other is; therefore, we all are Africans. Thus, the war against apartheid was won through a united front of activism. People must not forget this as quickly as they got the freedom they desperately sought.

Simply put, Desmond Tutu lived for human rights. He firmly believed that people should have the right to associate with, possess, or become anything that was not harmful to the generality of humans. He assiduously fought against any movement or organization that sought to oppress others and rob them of their rights. Tutu was a brilliant and convincing orator. Soon after he was ordained, he rose through the ranks to become the Bishop of Johannesburg in 1985, and, a year later, the Archbishop of Cape Town. He removed the gender barrier on priesthood in the country while in this primal position of the South African Anglican Church. The late Bishop was a man who understood the futility in trying to please everyone, so he just lived his life and embarked on endeavors based on his strong convictions. He never had a herd mentality. His support was always deep-seated and well-thought-out, which made some people think he was always overly cautious in playing safe.

Archbishop Tutu died at the old age of 90. He lived a long life, some periods easy, others more difficult. What more could anyone want? The anti-apartheid hero might not have asked for more, but good things surely came to him. His legacy demonstrates that when people choose to do good in whatever position they find themselves, and because they believe so much in the potency of doing good, then the deserved recognition will come, even if they do not actively seek it. Such was the case with our beloved Tutu.

He won several awards for his contributions to humanity and relentless push for the betterment of his people and the world at large. Among the awards he received was the prestigious Nobel Prize for Peace in 1984. The Royal Swedish Academy deemed the reverend worthy of the award for his immense contributions to the fight against the oppression of the apartheid government, and especially for his struggles to ensure a peaceful and non-violent demand for the people’s rights.

Another award that the reverend received was the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. The Presidential Medal of Freedom, considered one of the two most prestigious awards the United States of America can bestow on a civilian, was given to Desmond Tutu for his consistent contributions to the stability of world peace and other significant contributions to the fight for the peaceful co-existence of humans. In 2012, he received another prestigious award from the Mo Ibrahim Foundation for consistently speaking truth to power. This is a quality that many cannot boast of. Power corrupts, and once given access to power, many activists soon fail to see the need to continue to champion the struggle for the rights of the oppressed. But not Desmond Tutu. He spent his life believing that his power and position were given to him to help champion the cause of the marginalized and the oppressed, and if the oppressors were the leaders, so be it! Champion he must, and champion he was, speaking the truth, whether it went well with the powerful or not.

Conclusion

On Sunday, December 26, 2021, a day after Christmas, Desmond Tutu went to rest. The gravity of this demise is still a shock coursing through our veins, one that our brains have neither readily nor fully processed. We are still talking about his departure, and the largeness of the void it has left in true humanism is still unknown to us, until the moments we would need a fearless commentator and wonder what Desmond Tutu would have said. This humanist lived his life for the people. He believed in the people and believed God had plans for humanity. He believed that one of the greatest resources made available to us as humans is the ability to practice Ubuntu, and he preached this with every fiber of his being.

There have been long-lasting debates on the extent to which religion and religious views should be allowed in the activities of any state, especially democratic states. And while it is true that an allowance of interrelationships between law and religion could foster extremism, especially since there are several religious views, often differing, the practice of religion, as in the case of people like Reverend Desmond Tutu – who are humanists first and would put human needs before their religious beliefs – shows that religion can be positively used to formulate and enforce the law.

Indeed, the world has lost a great gem. Rest easy, Archbishop Desmond Tutu. You were an invaluable treasure and a blessing to the world. The whole world will sorely miss you. ♦

Toyin Falola is an African historian and the Jacob and Frances Sanger Mossiker Chair Professor in the Humanities and a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a Fellow of the Historical Society of Nigeria and a Fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Letters. Falola has authored and edited over one hundred books and serves as the general editor of the Cambria African Studies Series.

Recommended Citation

Falola, Toyin. “Desmond Tutu and the Intersections Between Law and Religion.” Canopy Forum, March 1, 2022. https://canopyforum.org/2022/03/01/desmond-tutu-and-the-intersections-between-law-and-religion/.