Incomplete Communities? Desegregating the City through the Reform of Land Use and Affordable Housing Policies

Alexander Ehlers

Suburbs of Primrose and Makause in Johannesburg. Maps Data: Google Earth (c) 2015.

This essay is part of a virtual conference series “The Roles of Law, Religion and Housing Through the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs)” sponsored by Canopy Forum and the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University. This series features scholars, experts, and practitioners who examine global challenges of homelessness, housing policy and housing vulnerability. You can browse all essays and view video presentations from the series here.

Progressive city planners aspire to create “complete communities” which are characterized by the availability – within a 15-minute walk – of all the amenities needed daily, and the integration of income groups in a single area. The ideal of complete communities represents an urban planning drive toward spatial equity, characterized by economic, racial, and spatial inclusivity, mixing and integration. Yet, South African cities remain highly segregated in terms of the residential areas, schools, shops, and modes of transport used by respective racial and income groups. Desegregation is thus a primary problem in South African spatial planning and land use policy. Taking the capital city Pretoria as an example, this essay outlines how current land use policy and planning maintains segregation and enforces homogeneity of communities. In turn, the essay argues that the project of desegregation cannot succeed without the introduction of key policy elements, like compulsory affordable housing, settlement upgrading and progressive land use management policies in favor of not only mixed use, but also mixed forms, sizes and value of buildings, and the development of an inclusive public transport infrastructure.

Introduction

District Six in Cape Town was destroyed in the late 1960s after being declared a whites-only area. This cosmopolitan home to Muslims, Jews, Christians, Hindus, and all races, was flattened and partially redeveloped into the whites-only area Zonnebloem. Most of those who called District Six home, were forcibly removed to the Cape Flats, a township on the outskirts of the city. Today, many are still scattered across the country, waiting for restitution.

District Six, Sophiatown in Johannesburg, and Cato Manor in Durban were suburbs holding iconic status as some of the few places in South Africa where a variety of racial, ethnic and religious groups lived together despite the growing force of pre-apartheid and early apartheid segregationist laws. In the twentieth century, “grand” spatial apartheid was legally provided for starting in earnest with the 1913 Natives Land Act which consigned black land ownership and tenancy to certain “native” reserves, followed by other legislation like the Natives (Urban Areas) Act of 1923 which further curtailed the ability of “non-whites” from living among whites. In 1936, The Native Trust and Land Act designated areas where black people owned land outside of the reserves to be “black spots,” and by the time of the commencement of the Group Areas Act in 1951 and the passing of the Natives Resettlement Act of 1954, the white minority apartheid government was continuing a decades-long program of reserving land for whites and forcibly removing so-called “non-whites” to the reservations and townships assigned to them.

Proclaimed in the place of District Six, the whites only Zonnebloem looked different from District Six, as Triomf in Johannesburg looked different from Sophiatown. Not only had these become racially segregated areas, but by the very layout of its streets and the neat zoning separation of land usages and building densities, aided in preserving the economic exclusivity of the new areas.

Land use policy and desegregation

The different “looks” of Pretoria suburbs provides an excellent example of how zoning practices may sanitize neighborhoods of certain economic classes, or of certain races, in a country where inequality is still substantially racialized.

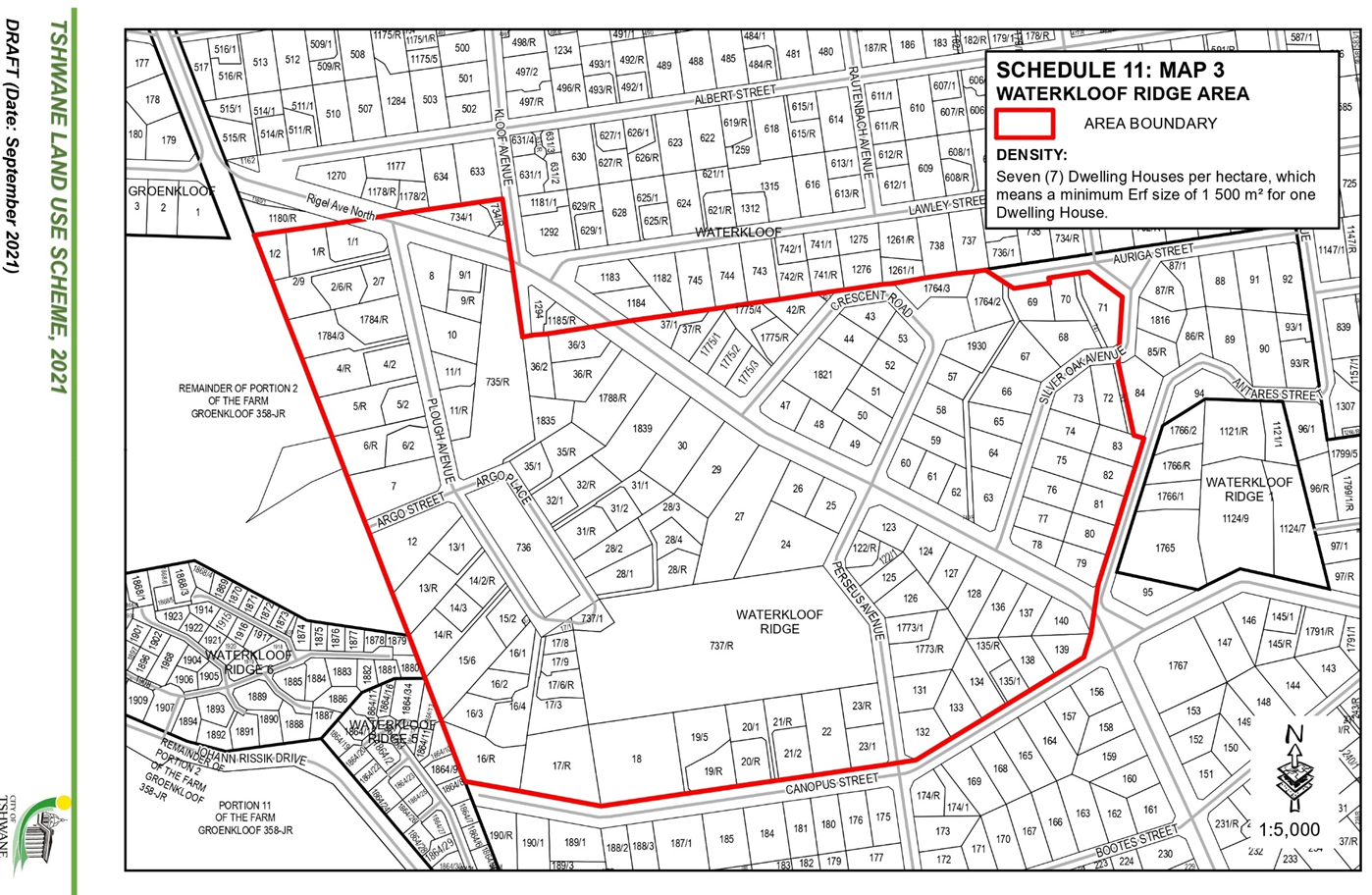

Waterkloof, for instance, is an upmarket suburb where land parcels are all very large, and the entire area is extremely homogeneous. This is largely because the existing town planning scheme (“Tshwane Land Use Scheme”) prevents higher density development by imposing certain caps on land coverage and minimum land parcel sizes. These are two examples of what planners call exclusionary land use measures, which have the effect of segregating the rich from the poor without doing so in name.

Creating such homogeneous rich enclaves means creating neighborhoods where only affluent, single families can afford to live, and which less wealthy sojourners are unable to easily navigate without public transport. Indeed, anyone without a car would be without easy access to daily amenities, as the Euclidian zoning of Waterkloof and its surrounds imposes a strict spatial separation of residential zones from shops and workplaces.

Minimum land parcel sizes and density caps especially have a significant segregating effect which maintains the historical exclusion of poor people from affluent neighborhoods and reinforces economic segregation and the formation of enclaves. The recent normative literature is already quite clear on this position, and there seems to be a growing empirical consensus that, as Lens and Mankkonen put it, “density restrictions lead to increased income and racial segregation,” and further that “spatial concentrations of poverty and wealth lead to unequal access to jobs, schools, and safe neighborhoods, and exacerbate negative life outcomes for low-income households.”

The American Planning Association’s 2019 Housing Policy Guide (pp. 8-9) recommends addressing existing exclusionary zoning practices by “reducing or eliminating minimum lot size requirements, reducing minimum dwelling unit requirements, allowing greater height and density” of development, and eradicating these exclusionary practices “that contribute to and continue historic patterns of segregation, which includes discriminatory definitions of family in local zoning and ordinances.”

Sunnyside is a lower income, high-density neighborhood. Instead of Waterkloof’s homogeneous, large low-density single-family lots exclusively for residential use, Sunnyside and Arcadia are characterized by a diversity of lot sizes, densities and use zones. Small scale shops and everyday amenities are within walking distance of all residents, making them accessible to those without cars. Housing is not segregated by income, as many kinds of housing exist in proximity, including traditional larger homes on their own plots right next to townhouse complexes and blocks of flats, as is common in Sunnyside East.

Planning literature refers to this phenomenon as a “complete community,” characterized by the availability, within roughly 15 minutes’ walking distance, of a near complete availability of shops and amenities, integration of income groups, different plot sizes and housing types and densities, integration of different land uses instead of separate zoning, and optimal mobility integration.

Complete communities represent a drive for racial equity and spatial integration, and this is indeed visible in an area such as Sunnyside East, where a great diversity of ethnic, religious and income groups live in the same neighborhood. Given how well exclusionary planning policies have maintained segregation in South African cities, the area is a very rare example of the desegregating potential of inclusive land use policy.

The County of Montgomery in Maryland has embarked on such a desegregating policy initiative with its plan for Complete Communities. The plan acknowledges that “the separation of uses and associated homogeneity in lot sizes, development standards and building forms, coupled with the commitment to barriers, buffers and transitions had the effect – whether intentional or not – of discouraging connections among people and places and reinforcing racial, social and economic divisions between neighborhoods and parts of the county.” This is coupled with separation of use zones and disproportionate investment in road infrastructure for access to key economic, educational, and cultural opportunities. As such, driving became the only practical way for many residents and workers to meet their daily needs – trips that should be feasible on foot, on a bicycle, or on a train or bus.”

There is an argument to be made that such segregating measures by way of zoning regulations is susceptible to legal challenge. In fact, there are precedents to be found from other jurisdictions where just such rulings on the illegality of exclusionary zoning measures were made.

In the New Jersey case of Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Township of Mount Laurel, 67 N.J. 151 (1975), the court was asked to rule on the justifiability of a town planning policy exclusively making provision for “single-family, detached dwellings, one house per lot the usual form of grid development,” so that other forms of housing such as apartments, town houses and mobile homes were not provided for.

This had the effect of realistically allowing “only homes within the financial reach of persons of at least middle income,” as the zoning areas required respectively minimum lot areas of 9375 and 1300 square feet, and respective minimum dwelling floor areas of 1100 and 900 square feet. The court observed that:

All this affirmative action for the benefit of certain segments of the population is in sharp contrast to the lack of action, and indeed hostility, with respect to affording any opportunity for decent housing for the township’s own poor living in substandard accommodations[…]

and that “needless to say, such requirements killed realistic housing for this group of low- and moderate-income families,” being the plaintiffs in the case.

The question before that court was whether the municipality unlawfully excluded low- and moderate-income families through its zoning regulations, and the court found that the municipality did indeed exclude such families unlawfully. The court made a set of moving comments in the closing paragraphs of the judgment:

It is not the business of this Court or any member of it to instruct the municipalities of the State of New Jersey on the good life. Nevertheless, I cannot help but note that many suburban communities have accepted at face value the traditional canard whispered by the “blockbuster”: “When low-income families move into your neighborhood, it will cease being a decent place to live.” But as there is no difference between the love of low-income mothers and fathers and those of high income for their children, so there is no difference between the desire for a decent community felt by one group and that felt by the other. Many low-income families have learned from necessity the desirability of community involvement and improvement. At least as well as persons with higher incomes, they have learned that one cannot simply leave the fate of the community in the hands of the government, that things do not run themselves, but simply run down.

Equally important, many suburban communities have failed to learn the lesson of cultural pluralism. A homogeneous community, one exhibiting almost total similarities of taste, habit, custom and behavior is culturally dead, aside from being downright boring. New and different lifestyles, habits and customs are the lifeblood of America. They are its strength, its growth force. Just as diversity strengthens and enriches the country, so will it strengthen and enrich a suburban community. Like animal species that overspecialize and breed out diversity and so perish during evolution, communities, too, need racial, cultural, social, and economic diversity to cope with our rapidly changing times.

Finally, many suburban communities have failed to recognize to whom the environment belongs. By environment, I mean not just land or housing, but air and water, flowers, and green trees. There is a real sense in which clean air belongs to everyone, a sense in which green trees and flowers are everyone’s right to see and smell. The right to enjoy these is connected to a citizen’s right to life, to pursue his own happiness as he sees fit provided his pursuit does not infringe [on] another’s rights.

South African apartheid urban planning was characterized by overt and covert pursuit of racial and economic segregation and exclusion. Pursuing complete communities seeks to use the tools of land use management to reverse the inefficient, iniquitous, and segregating effects of past planning approaches, and has the potential to make South African cities more inclusive.

Inclusive housing and desegregation

While the grand apartheid vision of local, provincial, and national planners led to the destruction of communities like Sophiatown or District Six, the imposition of land reservation for racial and economic minorities, post-apartheid city and regional planning have not been successful at reversing segregation. Housing the poor is where spatial apartheid is still most visible in South Africa.

While exclusionary zoning and land use policy has maintained the enclaves of the rich, it is arguably a lack of strong direction in inclusive and adequate housing policy and implementation that has preserved the iniquities suffered by the poor in South Africa.

South Africa’s Constitution provides for the right to “adequate” housing (section 26). Kulundu, following Muller, argues that the suitability of the location as well as the affordability of housing are key components in judging its “adequacy” in terms of the legal right to adequate housing. He further argues that inclusionary housing policies, understood as “positive measures to promote the housing right by specifically targeting well located land that can be used to build affordable housing and to bring about social and economic cohesion”, cannot achieve their goals without implementing a form of rent control and building controls.

In terms of land-use policy specifically, adequate housing policy initiatives would be limited to the regulation of new developments, rather than, for instance, mandating and implementing the provision of new social housing. That is generally beyond the scope of land use policy but may be pursued in other areas of planning law.

Whatever the case, for the elaboration of these two essential conditions for the success of inclusionary housing in terms of building and land use conditions imposed upon developers, Kulundu explains:

Building controls ensure that the right to build is regulated by linking this right to the provision of suitable, low-cost housing within a market-related development. This can serve the purpose of providing locational benefits to the occupants of the low-cost housing, as well as fostering social inclusion. Rent controls, although conceptually distinct from inclusionary housing programs, are often the result of the latter. They are aimed at affordability of housing and have often been the invariable result of inclusionary housing schemes.

Kulundu also asserts that rental controls may legally be imposed as part of the fairness concept under the Rental Housing Act, inclusionary housing also requires “positive measures under section 26(2) [of the Constitution] to protect the right to adequate housing”. Regulating the quantum of rent is also possible, as is already practiced by many municipalities across the world.

The Tshwane Metropolitan Spatial Development Framework (MSDF) states that “the crux of inclusionary housing policy is the “inclusion”, either voluntary or mandated through policy, of affordable housing with market-oriented units as part of private-sector housing developments. Affordable units in inclusionary projects are conveyed to low-income households, with the definition and income thresholds varying based on the locational context of implementation.”

The MSDF further states that “the spatial directives of Chapter 2 have been clear in that affordable housing should be channeled into activity nodes and corridors. Inclusionary housing should be responsive to this, and as such should be channeled towards the nodes identified within the MSDF.”

Yet, significant opportunities exist beyond the corridor and node-based approaches. As mentioned above, “complete community” approaches require spatial injustice redress beyond the creation of transit corridors and density nodes. Beyond just regulating housing along identified corridors, building controls in the form of development- and land use conditions that require that a prescribed minimum of social housing could be included in new developments.

Where new building is undertaken, great care must be taken to prevent gentrification and the further displacement of poor people accompanied by further high-income reservation of land. The MSDF proposal of corridor development might be progressive where densification and mixed use around transit-corridors like Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) trunk routes reverses earlier car-centered, Euclidian and exclusionary zoning practices. However, as Huchzermeyer warns, these are limited interventions which do not expressly address present living conditions of poor people. Unfortunately, the emphasis may fall on the eradication of informal housing in certain areas without the provision of positive housing measures like settlement upgrading or social housing provision, thus only moving the perceived problem to city margins.. Ultimately, substantial investment in social housing initiatives is arguably needed for any land use interventions to be successful, and vice versa.

The Montgomery Complete Communities plan mentioned before also highlights the potential of broader inclusionary interventions beyond corridors. It is crucially important for the success of inclusionary housing and informal settlement upgrading initiatives that housing developments are well located, and well-integrated with transport plans. Moyo and others studied different land-use driven development strategies directed at informal settlements and low-income housing. Their findings indicate that efforts to integrate informal settlements into the formal city through in-situ upgrading of settlements, in parallel with “targeted interventions aimed at ‘unlocking’ low-income housing activities along transport corridors were found to be useful,” but that these corridors, mixed as they are in use and income, may be vulnerable to pressures that could displace low-income earners through rental competition. In addition, in-situ upgrading is only a viable option if settlements are already in “areas with easy access to economic centers.”

The implication for land use policy is that interventions must be incorporated that prevent gentrification and can insulate social housing initiatives from rent-bidding. The inclusion of building and rent controls in land use management regulations are some examples of such protective measures. Considerations for “complete communities” should also be included in settlement upgrading and social housing initiatives.

This recommendation accords with Görgens & Dunoon-Stevens’s argument that land use policy “must take account of the whole urban form, and place the interests of all citizens ahead of the minority who can use their excessive share of capital to out-bid the average citizen.” Prevention of the displacement of the poor to the periphery of the city is especially important given that, as Durand-Lasserve argues, in South Africa, “market eviction process is tending to replace the forced evictions that prevailed in the 1990s, with similar effects on the poorest segments of the community. Although no figures are available at global level, empirical information clearly indicates that the magnitude of various forms of market-driven displacement now surpasses that of forced evictions.”

Conclusion

South Africa has not made significant progress in addressing the segregation of economic and racial groups which underlay the apartheid and earlier colonial spatial visions of our cities. These spatial iniquities will persist due to the formulation and implementation of strong inclusive desegregating spatial planning measures. Two prominent interventions discussed here include zoning reform to reverse the effective land reservation in favor of the wealthy, and secondly the adoption of broad inclusive and affordable housing initiatives which do not further marginalize the urban poor. ♦

Alexander Ehlers has lectured Jurisprudence in the Faculty of Law at the University of Pretoria and worked as a researcher on socio-economic rights and mining-affected communities with NGOs. He currently works on legal and philosophical aspects of land reform and privacy protection while pursuing postgraduate work. He writes in his personal capacity.

Recommended Citation

Ehlers, Alexander. “Incomplete Communities? Desegregating the City through the Reform of Land Use and Affordable Housing Policies.” Canopy Forum, March 20, 2024. https://canopyforum.org/2024/03/20/incomplete-communities-desegregating-the-city-through-the-reform-of-land-use-and-affordable-housing-policies/