Locke: The Slave Trader and the British Slave Trade

George Walters-Sleyon

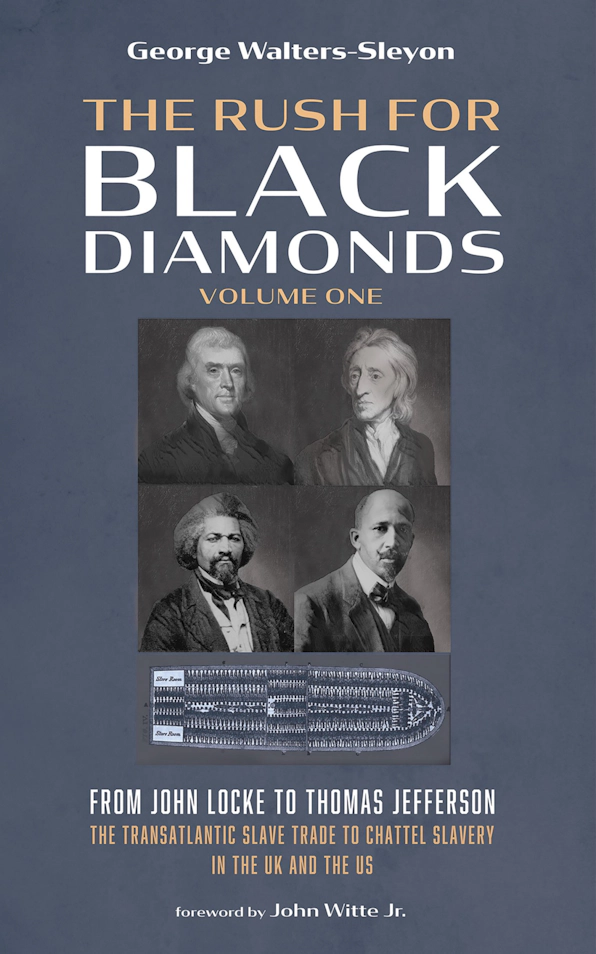

This essay is an adapted excerpt from the fourth chapter of George Walters-Sleyon’s book, The Rush for Black Diamonds, Volume One: From John Locke to Thomas Jefferson—The Transatlantic Slave Trade to Chattel Slavery in the UK and the US (Cascade Books, 2024). Used by permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers, www.wipfandstock.com

In 1668, Locke was appointed secretary to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina. According to Hinshelwood, The Lords Proprietors were basically managers of Carolina and profiteers of the slave trade. Locke had been a member of Ashley’s household for over a year, having taken up residence on a semi-permanent basis in the spring of 1667; at this point, Ashley made Locke secretary to the lords proprietors. Locke and his new employers immediately turned to crafting a constitution. The first edition of the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina is dated July 21, 1669, and portions of the manuscripts are in Locke’s hand (567). He supported Lord Ashley and seven other noblemen who possessed the right of proprietorship of Carolina. According to Woolhouse, “Locke acted as secretary of the lords proprietors until 1675, arranging and keeping minutes of their meetings, summarizing, and taking notes of official letters sent between England and Carolina, exchanging letters himself with officials in the colonies. His interest in the colony extended to devoting some thoughts to constructing a decimal system of coinage and measurement for it” (90-91). Concerning Locke’s position as secretary, Cranston notes, “The lords proprietors, who had the power to grant titles of nobility, bestowed on him in April 1671 the rank of landgrave in the aristocracy of Carolina—the title to be his and his heirs’ forever. At the same time, they gave him four thousand ‘baronia,’ or estates of land, in the colony” (120).

The Lords Proprietors were also slave traders (120). As members of the British Parliament, their responsibilities included managing the British colonies and all forms of colonial trade, including the slave trade. They also personally owned and controlled shipping companies plying the Atlantic Ocean from Britain to Africa, to the West Indies, and America. In addition, the Lords Proprietors managed the colony of Carolina in America. “Locke was granted the second highest rank, of ‘Landgrave’ and forty-eight thousand acres that came with the title,” as well as the provision that “every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slave of what position or religion so ever” (203). The legal justification for slavery in Britain was based on common and commercial legal concepts. Finkelman notes, “Slavery in the British Empire would be governed by local laws, haphazardly passed by colonial legislatures or developed by colonial courts responding to specific events and cases. This would lead to a complicated legal structure for slavery in the colonies and later in an independent United States of America” (107). In the United Kingdom, politicians of all stripes were involved in the slave trade as ship owners and plantation owners in the West Indies and the Caribbean. On March 1, 1669, John Locke wrote the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, the state’s founding document, which included the stipulation that “every freeman of Carolina, shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves, of what opinion or religion soever” (115). Locke and his fellow Lords Proprietors needed a constitution to govern this colony, and the Fundamental Constitutions of the Carolinas was produced in 1669 as a response to this need (563).

As secretary, Locke served as the architect of the Fundamental Constitutions, a significant document stipulating the power and authority a slave owner had over his slaves, including “liberal policies and restrictive social hierarchies” (265). According to Armitage, “no major political theorist before the nineteenth century so actively applied theory to colonial practice as Locke did by virtue of his involvement with writing the Fundamental Constitutions of the Carolina colony.” Armitage contends that the Fundamental Constitutions reflect the intersection between Locke’s “political theory and his colonial interests.” In addition, it “assumed the existence of slavery and affirmed the absolute powers of life and death of slaveholders. They also erected the first hereditary nobility on North American soil” (607). Cranston, however, rejects the claim that Locke was responsible for the Fundamental Constitutions. He notes: “A copy, in Locke’s hand, of The Fundamental Constitutions for the Government of Carolina which reposes in the Public Record Office, has long been familiar to students of Locke. The fact of its being in Locke’s hand has led many such scholars to conclude that Locke composed it, whereas that circumstance is in fact evidence only of Locke’s secretarial services to the lords proprietors” (119). Cranston makes this argument notwithstanding Sir Peter Colleton’s appeal to Locke in a letter written in 1674 referencing “that excellent form of government in the composure of which you had so great a hand” (120).

Sir Peter Colleton had a brother by the name of Sir John Colleton. He was also one of the most prominent Lords Proprietors of Carolina. Sir Peter Colleton was in all earnest, referring to the Fundamental Constitutions. Based on minutes recorded in a notebook in 1672, Locke was present at all expected gatherings of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina up to June of 1675.

Just about the time the Fundamental Constitutions were published in 1669, the state of Virginia was passing laws regarding slavery. Central to the Fundamental Constitutions are the rights of slave masters, including the Lords Proprietors. In addition to the slave owners, Carolina contained many freemen. According to the Fundamental Constitutions, the slave masters and freemen of Carolina had “absolute power and authority over his negro slaves.” The slave had no right that the above masters were obliged to recognize, respect, or implement. In Article 111, Locke makes it clear that the freemen, the Lords Proprietors or the ordinary slave masters could not be brought before the court for any “civil or criminal” offence “without a jury of his peers.” Slave masters acted with absolute impunity. In 1669, an Act was passed in Virginia stating that if a master kills a slave by punishment, the death was not considered a crime. The slave was property and part of the estate; because of this, the slave master could not face punishment for the death of a slave. The law stipulated that the death of the slave at the hand of the master was a casual occurrence and could not be based on a “prepansed malice” (premeditated) (114). The industry of the slave trade and the institution of chattel slavery were eras of blatant White-supremacist brutality against Black humanity and personhood. The black diamond was a thing of economic utility, sexual abuse, and cruel destruction. Just as they were denied Enlightenment justice and fairness, Blacks were denied common-law justice, fairness, and protection as slaves. Slaves were “wild beasts” and property to be protected against and to “protect” as economic units. Finkelman notes: “With these two statutes Virginia had adopted one of the central aspects of the Roman law of slavery—that it was not a criminal act to kill a slave” (114). One can argue that the Virginian laws of 1680 and 1691 regarding the punishment of slaves became the preamble to the post-1970 increase in rates of police brutality against Black people. Virginia established the legal foundation by which Black people were legally defined as slaves, property, and real estate. The right of the master over his slave is clearly stated in Locke’s Fundamental Constitutions of the Carolinas, in which he argues that the slave master has total power over their slave (103).

In 1673, Locke lost the position of Secretary of Presentation to Shaftesbury in Parliament. However, the same year, Locke “was sworn in” as the secretary of the Council of Trade and Foreign Plantations; the earl served as the council’s president. Locke’s positions brought him into personal contact with the regulators of British trade, including the slave trade in the North American colonies.

LOCKE: SECRETARY AND INVESTOR IN THE SLAVE TRADE

In addition to the theoretical and bureaucratic responsibilities of his position, Locke was also personally involved in the slave trade. He was a merchant adventurer—one of the many highly placed investors and slave traders within British trading companies. Locke invested his initial 200 pounds in the industry and continued to invest in the industry throughout his life. In his position as secretary, Locke was meticulous in gathering information about the “colonial trade and plantation life.” He served in the Council of Trade and Foreign Plantations until 1674 and received a handsome annuity from Shaftesbury (156).

In 1676, Locke was elevated to the position of secretary to the Council of Trade and Plantations. His role as secretary of the Council of Trade and Foreign Plantations was also based on how well he had executed his responsibilities as secretary of the Lords Proprietors. In this position, Locke had a bigger platform to craft and structure the policies of the British Empire regarding the slave trade, a business that he had a personal stake in. In all of these positions, Locke was not an idle bystander and accidental participant. His intellectual ability and socio-political connections were integral to the perpetuation of slavery. Woolhouse explains that “in October (1676), Locke was sworn in his place, at an annual salary of 500 Pounds, taking on further responsibility the next month as Treasurer (at 100 Pounds a year). Many of his letters in this and the following year are witness to his involvement with both the Council and the lords proprietors of Carolina, and also to his own interest in the Bahamas” (114).

In his many prestigious positions, Locke became one of the most sought-after architects of the slave trade in the British Empire. He had expertise regarding the practice and policies of the slave trade at the local, national, and international levels. Locke’s knowledge and influence extended to the British colonies in America, including the Carolina colony and Virginia—the home of Thomas Jefferson. In 1696, Locke became commissioner of King William’s New Board of Trade. The focus of this board was on crisis management in the colonies of England, including those in North America (280). The board intervened in colonies with poor governance and attempted to solve problems, including piracy and ineffective trade regulations. Glausser notes that “in this position, [Locke] was unquestionably an active policy-maker . . . the leading Commissioner in nearly everything which was undertaken.” (199-216) Locke’s positions as regulator and policy adviser were related to the slave trade, and his elevation to these prominent positions was not coincidental.

Locke was not a bystander or accidental participant in the transatlantic slave trade. He was involved at the highest level of the slave trade as a political appointee of the British Parliament. Locke was responsible for formulating and executing policies related to the human trade and all trade relations for the British Empire. Furthermore, these communications showed that the concept of “Lockean slavery” received its formal origin in the British Parliament. Lockean slavery is Britain as a slave trader, slave master, and a colonial master of Africans in the Americas, the West Indies, and Africa. It was Locke’s responsibility to provide the philosophical and political justification of the transatlantic slave trade, the institution of slavery, and chattel slavery with the blessings of the British Parliament. While Du Bois’s account reflects the industrialization of the slave trade as Jeffersonian slavery in the United States, Locke is, on the other hand, the embodiment of the British account of the industrialization of the slave trade and its political and philosophical justification before the American Revolutionary War and thereafter.

Locke’s involvement in the slave trade took a new turn in 1671 after the dissolution of the old Company of Royal Adventurers. In its place, the Royal African Company emerged and, with the full participation of Locke, Ashley, and Colleton, transported close to ninety thousand slaves from Africa to the British colonies (89). Britain collected taxes on slaves imported through the slave trade, which became the ultimate source of profit, revenue, and labor (134). According to Finkelman, “the Royal African Company’s investors reached the highest echelons of British society, including members of the royal family. Even after the demise of the Royal African Company in 1750, the slave trade continued to be an important part of Britain’s mercantile policy” (134).

In 1672, Locke, by now a Landgrave of Carolina, joined Ashley’s new company of merchant adventurers with the purpose of trading with the Bahamas. According to Farr, “In his portfolio, then, he smartly complimented stock in the Royal African Company with stock in a company of Merchant Adventurers with much investment in the human trade” (267).

Locke was a partner with his patron Lord Ashley in the Bahamas venture along with five Carolina businessmen who served as custodians of the Bahamas islands in 1672 (201). He was also one of eleven “Adventurers to the Bahamas” whose goal was to bring development to the Bahamas through the slave trade. Glausser explains that Locke had initially invested £100 in the Royal African Company and later took over the share of his partner John Mapletoft. “He was present on the 8th of November [1672] at a meeting on board the ship Bahamas Merchant, moored in the Thames, and ready for the sailing” (202).

The institution of slavery was important for two main reasons: (1) slaves were economic units, and (2) slavery provided cheap labor and wealth generation. The slave trade and slavery were legal and legitimate means of income, as the Laws of the United Kingdom of Great Britain supported it. In 1673, Locke invested in The Company of Royal Adventures in England and Trading into Africa. The company was given a monopoly on the slave trade on the West Coast of Africa. Robert Bernasconi and Anika Mann explain that “by 1665 one quarter of the company’s trade was in slaves, and in 1667 it claimed to be delivering six thousand slaves to the plantation each year” (89).

Slavery brought Locke financial and social elevation as secretary, controller, and regulator of the British trade and the American colony. According to Cornel West, the “racialization of American slavery was rooted in economic calculations and psycho-cultural anxieties that targeted black bodies. Thus, the profitable sugar, tobacco, and cotton plantations of the New World were housed and husbanded by African labor, with the result that African men, women, and children defined the boundaries of European culture and civilization.” (89) Locke’s participation in the slave trade was for economic gain (202). Locke remained in Shaftesbury’s colonial affairs until late 1682 when Shaftesbury fled to Holland and fell mortally ill (497).♦

Dr. George Walters-Sleyon is an Author, Professor, Speaker and Consultant with an interdisciplinary and broad international academic background. He has served as a keynote speaker, presenter, and panelist at conferences in the US, the UK and Africa. He has published several articles and books: Locked Up and Locked Down: Multitude Lingers in Limbo Revised Edition; Nuggets from the Night: An Anthology of Poetic Expressions; Prison Chaplains on the Beat in US and UK Prison Caring for Aging, Dying, and Dead Prisoners; and God in the Name of Jesus Christ. His recent book is The Rush for Black Diamonds, Vol. One. Volume Two of The Rush for Black Diamonds and is set to be released in October 2025 by Cascade Books/Wipf and Stock.

Recommended Citation

Walters-Sleyon, George. “Locke: The Slave Trader and the British Slave Trade.” Canopy Forum, September 19, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/09/19/locke-the-slave-trader-and-the-british-slave-trade/.

Recent Posts