Complexifying Psychedelic “Mysticism”: Analytical, Therapeutic, and Legal Considerations

Jay Michaelson

AI image made by the author to demonstrate Aldous Huxley‘s writing.

“Mysticism” – the experience of union with ultimate reality – is often described as a summum bonum of human religious experience, and a central feature of the psychedelic experience. Indeed, in describing psychedelic experiences, “mystical experience” is one of the most frequent terms found in scientific studies, therapeutic manuals, legal documents, and popular accounts. Psychedelic researchers Frederick Barrett and Roland Griffiths, drawing on the classical twentieth century definition of mysticism, define such experiences as:

those peculiar states of consciousness in which the individual discovers himself to be one continuous process with God, with the Universe, with the Ground of Being, or whatever name he may use by cultural conditioning or personal preference for the ultimate and eternal reality.

Despite the frequency of its use, however, the term “mysticism” is too analytically narrow, diagnostically inadequate, and legally misleading when applied to the range of experiences psychedelic users report. The term should be retired in favor of a more capacious, less theologically-specific category such as “Spiritual/Existential/Religious/Theological” (SERT), an acronym proposed by my colleagues at the Emory Center for Psychedelics and Spirituality. Here, I will review the analytical shortcomings of the term in understanding religious experience and the variety of altered states of consciousness that arise in therapeutic contexts, and then turn to the legal and political consequences of this confusion.

Phenomenological and Historical Narrowness

First, “mysticism” is too narrow a term to describe the breadth of psychedelic spiritual experiences, and misses some of their most impactful aspects as described by psychedelic practitioners. As usually defined, mystical experience is one of union, ego-dissolution, self-transcendence, ineffability, and joy or rapture. And sometimes, such experiences do arise – personally, I have found them to be enormously beautiful, even transformative.

But across the span of human history, the vast majority of psychedelic use has taken place in indigenous contexts which describe very different non-ordinary experiences: non-unitive rather than unitive, challenging rather than rapturous, and perhaps most importantly, dualistic, involving not union with the “Ground of Being” but encounters with entities from nature, from other realms, and from spiritual dimensions, as those broad categories are understood in different cultures.

There is an obvious reason for this incongruity: the priority given to “mysticism” developed in a particular historical context, and a rather unusual, syncretic one at that: the 20th century Christianized Neo-Vedanta practiced by scholars and researchers like William Stace, Aldous Huxley, and Walter Pahnke. The problem isn’t that mysticism doesn’t exist; it’s that it exists in a specific theological context and is then projected onto others in which it does not really apply. For example, in Christian contexts, the category is often incomplete: Ron Cole-Turner has pointed out that the classical definition of mysticism does not include the central quality of Christian mystical experience: love. In Jewish contexts, Boaz Huss has discussed at length the ways in which Kabbalah, usually described as “Jewish mysticism,” rarely contains the attributes of the mystical experience as classically defined. On the contrary, as Melila Hellner-Eshed has shown, the spiritual-mystical experiences in the Zohar, the masterpiece of Kabbalah, are often quite different from the classical definition. And in Hindu contexts, the Neo-Vedanta of Ramakrishna, Vivekananda, and other nineteenth- and twentieth-century figures. relegated Hinduism’s many forms of deity worship to a lesser status, and claimed mysticism to be a universal philosophy that reflected the essence of every religion.

This view of mysticism is an essential ingredient in Perennialism, a 19th and 20th century view that all religions share the same, mystical, non-dogmatic, non-textual, and non-mythical core – what Huxley called the “perennial philosophy.”

The problem with this view is that, as the saying goes, when the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. The only way to assert a single mystical core to world religions is to selectively winnow out the vast majority of what religions actually teach: ethics, myths, theologies, communal stories, philosophies. Even within spiritual experiences narrowly, the focus on “mysticism” flattens the diverse experiences that actually exist in world religious literatures, and relegates to some lower ‘level’ those that are dualistic, anthropomorphic, biomorphic, or otherwise non-unitive (surely, the vast majority of spiritual experiences in history). This hermeneutic is both inaccurate and, frankly, offensive, and has been disproven religious scholars for decades. Coming across it so often in psychedelic contexts can be jarring, like a throwback to the last century.

Though mystical union is sometimes regarded as the summum bonum of psychedelic experience, in fact it is a very specific, historically constructed category. Ultimately, it is not descriptive but normative. And as we shall now see, this is not merely an intellectual matter; it has scientific and legal relevance as well.

Therapeutic inadequacy

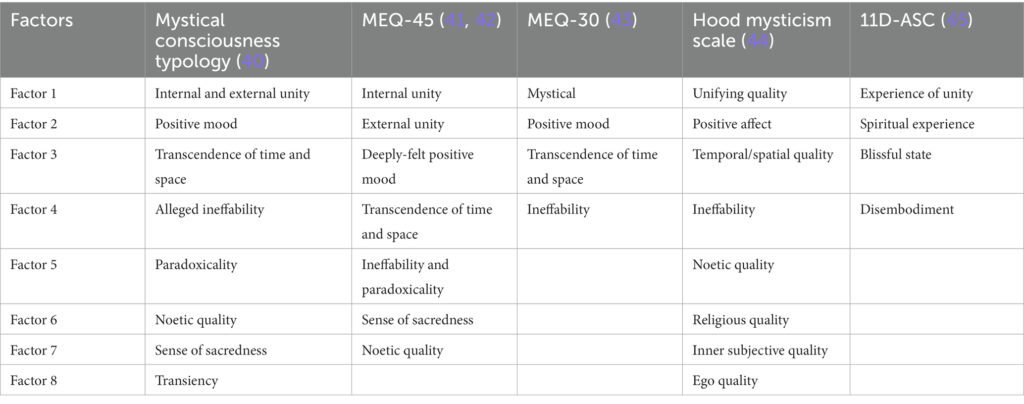

In the twentieth century, spiritual-mystical experiences ceased to be the results solely of divine grace or arduous spiritual practice: they could also be generated by psychedelics. In the first wave of psychedelic research (1945-1970), scientists as well as scholars were interested in understanding the nature of such experiences and their relationship both to mental health and to human potential more generally. Thus, heavily influenced by Stace, Pahnke wrote the first version of the “Mystical Experience Questionnaire” (MEQ) in 1963. The MEQ has been revised over the years, yet still tracks the perennialist conception of mysticism quite closely. A recent article in 2023 by Sharday Mosurinjohn and fellow researchers provides a good analysis of the MEQ factors of mystical experience.

In the second wave of psychedelic research (1994-present), scientists have used the MEQ to assess the phenomenology of the psychedelic experience, and various studies have shown that high scores on the MEQ correlate with better mental health outcomes.

But is the MEQ measuring the right factors? According to many psychedelic experiencers, and many indigenous practitioners, much of the “work” of psychedelic spirituality or therapy happens in more dualistic mental states: the experience of encountering entities, for example, or revealing aspects of one’s own unbconscious mind. Perhaps the MEQ is merely measuring correlation rather than causation, not to mention imposing a very specific (and recent) framework on the diversity of psychedelic SERT experiences. Indeed, it may be the entirely wrong yardstick to use if we are interested in the experiences that lead to positive mental health outcomes; it may also, as some researchers have pointed out, impose theological categories on experiences that may not be intrinsic to the experiences themselves.

It’s even possible that a patient’s orientation toward mysticism could obstruct the factors that would lead to positive mental health outcomes. An experiencer focused on ego death, for example, may miss the more important opportunities for personal growth and healing that arise in non-unitive experience. A facilitator attending to mystical experience may fail to attend to adverse events, or may justify them in the same of that summum bonum. For that matter, the relevant aspect of psychedelic healing may not even be the individual experience at all but the communal experience – with other experiencers; with a therapist, facilitator, shaman or other guide; or, for that matter, with spiritual guides, ancestors, and spirits. The focus on mysticism may impede the measurement of psychedelic experience and the implementation of psychedelic assisted therapy.

Legal and Political Confusion

Finally, the focus on mystical experience adversely shapes the legal regimes and political realities currently governing psychedelic use.

Historically, courts have viewed construed psychedelic religious use narrowly: as indigenous or indigenous-adjacent consumption of a Christian-like “sacrament” that is protected by the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). This framework aligns with the focus on “mysticism”: consume sacrament, undergo mystical experience. But it does not align with how many psychedelic churches, indigenous communities, and Abrahamic religious communities understand their psychedelic religious practice. As we have already noted, mystical experience is but one of the purposes of cultivating altered states of consciousness; others may include healing; access to power, prophecy, or information; contact with supernatural entities, ancestors, or nature spirits; and building community bonds or social structures.

This is true both historically and in contemporary practice. For example, at a symposium held at Harvard Law School in March, 2025, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim practitioners movingly described experiences of healing intergenerational trauma, building social bonds, experiencing deeper connections to their religious traditions, and numerous other non-unitive, non-mystical transformations. These goals are not captured either by the narrow focus on the consumption of a sacred substance (sacrament) or by the hyper-individualistic focus on mysticism.

The law has struggled to reflect these realities. For example, until very recently, courts and the DEA have been reluctant to mix “religious” and “therapeutic” uses of psychedelics. (The recent case of Jensen v. Utah County may test this distinction, but the final result will not be known for some time.) But that distinction often does not exist in actual psychedelic practice; for example, the term curandero as a title for a psychedelic guide encompasses spiritual, mental, and even physical healing. Individual mystical experience may seem ‘purely religious’ but it does not reflect the breadth of religious psychedelic use as actually practiced The law is not protecting what it ought to protect.

Politically, as states consider ballot initiatives that would decriminalize some psychedelic use, and as new religious claims continue to be made, it matters that sincere religious psychedelic use is not merely about the thrill of the mystical experience but is sometimes integrated into communal structures, ethical norms, and rectifying familial relationships. Mystical experience sounds a lot like getting high; the purpose of the trip is to have the most mind-blowing experience possible. Yet, over and over again in religious literatures, the main value of altered state experiences is not the mind-blowing experience but the insights one derives from it. Moses comes down from the mountain, the curandero intercedes on behalf of the community, the Sufi’s experience of Divine love generates love of other human beings. Better conveying the diversity and depth of psychedelic SERT experiences can lead to better communication with the public about what religious psychedelic practice is all about.

Previous generations of psychedelic pioneers did not use the word “mysticism” maliciously. Due in part to their own spiritual practices, and in part to the phenomenology of the LSD and psilocybin experiences, they understood their profound spiritual experiences in mystical terms. And personally, I love unitive mysticism. I love studying it, practicing it, and writing about it, and I resonate strongly with Huxley’s neo-Vedantic experience of istigkeit.

But the mystical is but one experience of many. As beautiful as it is, it should not limit our understanding of a much wider and more diverse set of religious experiences, how they may aid in promoting mental health, and how the law should protect them. ♦

Jay Michaelson is a Field Scholar at the Emory Center for Psychedelics and Spirituality and a Visiting Researcher at Harvard Law School. He holds a PhD in Jewish Thought from Hebrew University, a JD from Yale Law School, and nondenominational rabbinic ordination.

Recommended Citation

Michaelson, Jay. “Complexifying Psychedelic “Mysticism”: Analytical, Therapeutic, and Legal Considerations.” Canopy Forum, October 10, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/10/10/complexifying-psychedelic-mysticism-analytical-therapeutic-and-legal-considerations/.

Recent Posts