The Problem with the Peace Cross

Adam McDuffie

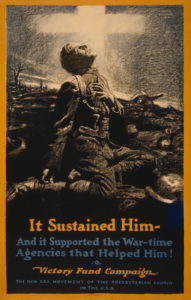

Bladensburg World War I Memorial. Bladensburg, Maryland. Flickr. CC BY 2.0.

In its recent decision in American Legion v. American Humanist Association, the Supreme Court has once again drawn conclusions grounded in a faulty reading of history. Ruling 7-2 that a 40-foot cross located along a highway in Bladensburg, Maryland does not violate First Amendment restrictions on government-sponsored religious displays, the Court simultaneously impinged upon prevailing understandings of the Establishment Clause and labeled a symbol held to be of great religious significance by many Americans as purely secular. The American Humanist Association argued that the so-called Peace Cross, which was erected in the 1920s as tribute to soldiers who lost their lives in World War I and stands on public property, constituted a government establishment of religion. This argument was based on their interpretation that the cross not only “incorporated religious symbolism,” but in fact was a religious symbol. The court rejected this characterization, allowing the cross to remain in place for the time being.

A central element of the Court’s ruling was the history of this particular cross, which the Court understood to establish that the Peace Cross is not a religious display at all. However, the history the court draws on is flawed. Justice Alito, in his opinion written for the majority, describes the cross as a symbol adopted during WWI without any particular religious meaning. He argued the symbol was generalized and secularized to be broadly representative of the sacrifice of soldiers, Christian or otherwise. While it is true that the cross was widely used to commemorate sacrifice during the war, to presume this to be a secularization of the symbol would be wrong. To do so ignores the religious sentiments driving the cross’s adoption as a popular symbol during the war.

While it is true that the cross was widely used to commemorate sacrifice during the war, to presume this to be a secularization of the symbol would be wrong.

WWI represented a turning point in the way the world waged war. Technological advances enabled armies to wreak death and destruction on an unprecedented scale. Only a few months into the conflict, the war appeared to be a futile waste of lives as soldiers languished in trenches and strived to gain a few feet of ground at great cost only to perhaps lose it again the next day. The nations fighting the war sought a means of ensuring continued public support for the conflict and a steady stream of enthusiastic new recruits to fight it.

George Mosse, in his work Fallen Soldiers, speaks to the forces which helped to preserve this commitment to the war. He calls this the Myth of the War Experience, which embraced an “ideal of personal and national regeneration which . . . only war could provide.” This myth portrayed war as “sacred, an expression of the general will of the people,” and appropriated Christian notions of death and resurrection to ease fears surrounding the death of soldiers. Death resides at the center of “war as a human drama,” and the Myth of the War Experience attempted to provide a “happy ending.” Those who died in grand service to the nation were not truly dead, they were resurrected and their memories resided with the community, and the cross was frequently deployed as a symbol of this communal eschatological hope. The seeming futility of trench warfare was minimized as the soldiers were cast instead as valiant heroes offering themselves for sacrifice to a grand cause in the template of Jesus Christ’s death on the cross. Through national monuments and cemeteries characterized by frequent usage of cross imagery, as the court notes, the nation could continually access and pay tribute to this class of fallen saints. In fact, Mosse casts these as “analogous to the construction of a church for the nation.”

The Court is thus correct that the cross came to symbolize the war generally. But the cross was by no means emptied of its religious significance. The Court’s claim ignores both the roots of the specific cross at issue in American Legion and actually constitutes a harmful cheapening of the cross as a symbol of great significance to Christians. The community in Bladensburg chose the symbol of the cross because of the meaning inherent in the cross as a Christian symbol. At the time of its dedication, it was referred to as the Calvary Cross, and a member of Congress participating in the ceremony evoked the role of the cross, “symbolic of Cavalry” to “keep fresh the memory of our boys who died for a righteous cause.” The cross did not so much take on “an added secular meaning,” as the Court presumed, as its religious significance was appropriated for patriotic means. To presume that a nationalistic expression is free of religious sentiment is wholly incorrect.

The American Legion decision also signals cause for concern over the Court’s role as an arbiter of American social memory. The Court interprets law through history, and the precedent the Court establishes is used by lower courts, the government, and the public to assess events in American life. The Court’s recasting of the war memorial cross as a secular symbol threatens to alter the nation’s memory of this particular symbol with very real consequences for the application of the Establishment Clause.

There is a legitimate discussion to be had regarding whether or not the removal of the Peace Cross would constitute an excessive burden on the community. However, if the Court wishes to root any part of its decision in the history of the usage of crosses as symbols of military sacrifice, it must acknowledge the role of religion in shaping the meaning of these symbols. The Court felt satisfied that the cross was erected in a different time when the cross had a different meaning, but this is ignorant of history. As Justice Ginsburg stated in her dissent, a cross is never just a cross. The symbol has been indelibly shaped by its legacy as a symbol of the Christian faith, and that very symbolism is what generated its importance as a symbol of sacrifice in World War I. Knowing this, it is difficult to comprehend why the Court would allow the cross to remain.

Adam McDuffie is a third year PhD student in American Religious Cultures at Emory University. His work probes the intersections of religion, politics, and law, with a particular focus on the place of soldiers and soldier bodies in American civil religion.

Recommended Citation

McDuffie, Adam. “The Problem with the Peace Cross.” Canopy Forum, November 20, 2019. https://canopyforum.org/2019/11/20/the-problem-with-the-peace-cross-by-adam-mcduffie/