Religion-Making in Japan’s Courts of Law

Ernils Larsson

Photo from Unsplash

When Japan set out to reinvent itself as a modern nation-state in the second half of the 19th century, the new generation of policymakers had to navigate a plethora of foreign concepts as the vocabulary of Western thought was translated into Japanese. While many of these concepts were essentially new philosophical outlooks easily adapted to the political situation in Japan (e.g. “liberalism,” “conservatism,” “capitalism”), others forced a reorganization of how the Japanese language had made sense of reality. Amongst these was “religion,” a term thoroughly intertwined with the particularities of the development of Christianity in Europe, but which in the 19th century had been granted a new status as a generic category applicable in various national contexts. Interpreting religion in Japan was immediately tied to questions of diplomacy, as the Western powers vying to sign treaties with Japan all demanded that Japan allow freedom of religion, an ideal which at the outset was completely foreign in a language with no term corresponding to the Western “religion.” This led to what Trent E. Maxey has referred to as “the greatest problem,” as Japanese lawmakers over the subsequent five decades set out to not only translate “religion” (shūkyō became the agreed upon term in the 1880s), but also to establish what this concept meant and what its limits would be. This was in many ways the first period of “religion-making” in Japanese history.

When the Meiji Constitution was proclaimed in February 1889, it reflected the decision to ensure that religion as a concept remained a matter of private belief, separated from the state. Under Article 28, it was stipulated that Japanese subjects would “enjoy freedom of religious belief,” as long as this was “within limits not prejudicial to peace and order” and “not antagonistic to their duties as subjects.” Religious freedom under the Meiji constitution was envisioned as primarily a right granted to individuals, conditioned on their behavior as dutiful imperial subjects. Although plans for a law regulating religion as an expression of collective belief was proposed around the time the constitution was proclaimed, it was not until 1939 that the Religious Organizations Law was finally passed, providing the framework for how religions would be allowed to organize in the secular Japanese state. Prior to the Japanese defeat in World War II, religion was understood as a set of optional beliefs to which lawful subjects were free to adhere. The category mainly included Buddhism, sectarian Shinto, and Christianity. Though the emperor was granted a prominent position by virtue of his divine origins, and though numerous public rites and ceremonies were carried out at Shinto shrines, the notion that Imperial Japan had instituted “State Shinto” as a “state religion” is, as Jolyon Thomas has argued, “both legally inaccurate and historically misleading.”

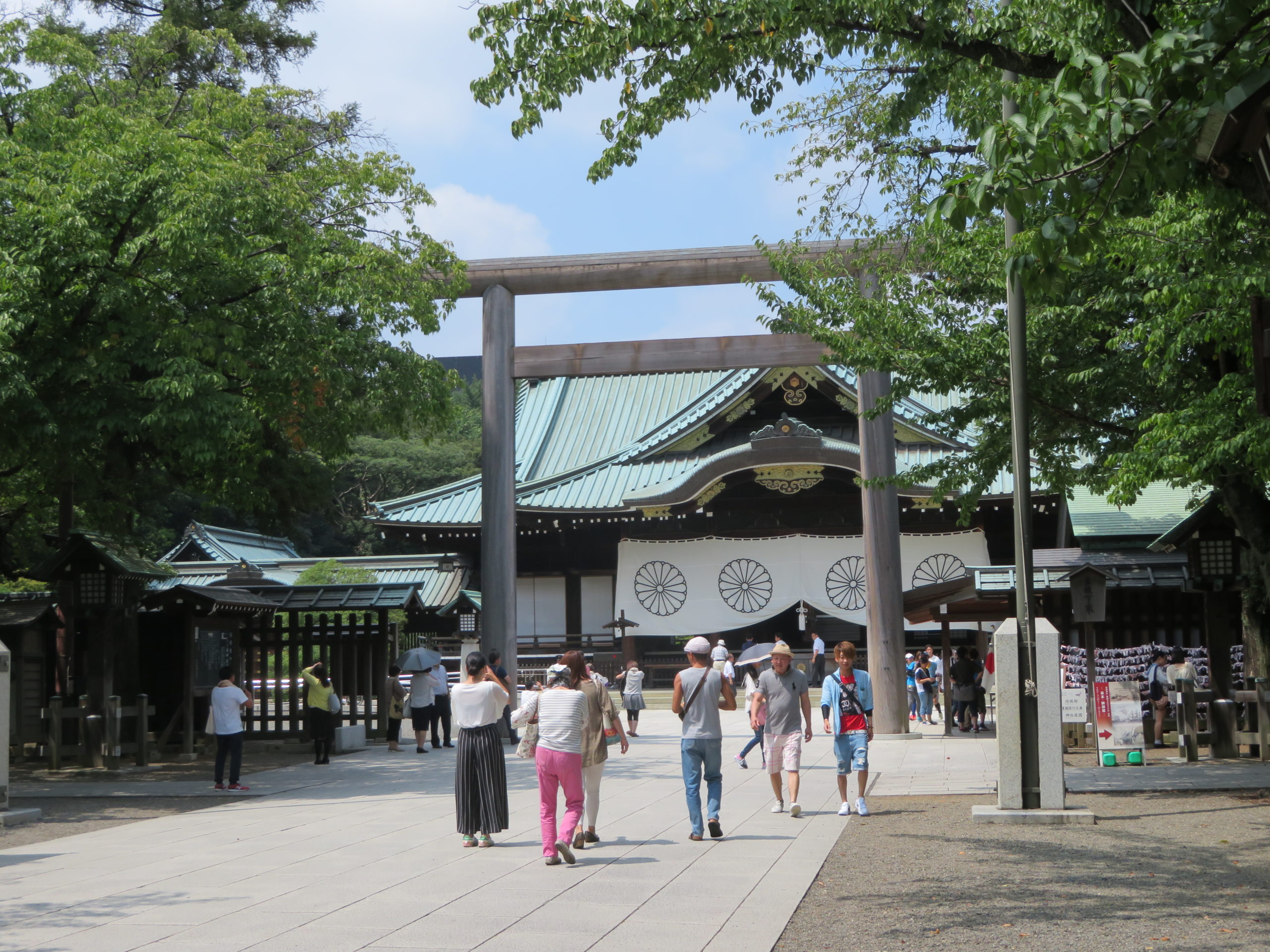

Yasukuni Shrine, Tokyo. Image Courtesy of Author.

A second period of religion-making in Japan commenced as the country was occupied by the Allied forces after Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945. Revising the Japanese constitution was an early goal of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan, General Douglas MacArthur. After Japanese policymakers had shown a reluctance to go through with the reforms he considered necessary, MacArthur set up a small workgroup of predominantly American servicemen who were tasked with the project of drafting a completely new constitution in February of 1946. Although the constitution was presented as a revision of the previous constitution, the end result was an entirely new text, based predominantly on the liberal constitutions of the United States and Western and Northern Europe. The constitution was envisioned as the stepping stone in creating a new Japan, remodeled as a liberal democracy. Reflecting the trends of the day, many fundamental human rights and freedoms were inscribed into the text, establishing Japan as a pacifist state and forever renouncing war as a sovereign right of the nation.

While religion was nominally separated from the state and compartmentalized as a matter of individual belief, the Americans considered the prewar regime’s idea of what constituted “not-religion” to be false.

In a recent work, Jolyon Thomas has argued that the Americans in charge of the initial stages of the occupation of Japan considered the prewar system to have been a form of “heretical secularism.” While religion was nominally separated from the state and compartmentalized as a matter of individual belief, the Americans considered the prewar regime’s idea of what constituted “not-religion” to be false. In Thomas’s argument, “State Shinto” was essentially created during the early months of the Allied occupation in order to ascribe a formal “state religion” to the previous order, which could then be formally disestablished through the December 15, 1945 Directive on the Disestablishment of State Shinto (“Shinto Directive”). Through this directive, much of what had previously been part of the national ideology was reconceptualized as a religion, “Shrine Shinto,” and consequently became a matter of private belief rather than national identity. Through this process of religion-making, Shrine Shinto came to be understood as one of Japan’s religions, to be treated in the same way as Buddhism, Christianity, or any other faith.

Much like Article 9 of the postwar constitution was written against Japanese militarism, so too were Articles 20 and 89 a response to State Shinto. Article 20 makes it clear that religious freedom is to be guaranteed to all citizens and that no one can be compelled to partake in any form of religious act or rite, but it also raises a wall of separation between religion and state. Paragraph 1 establishes that no “religious organization shall receive any privileges from the State, nor exercise any political authority,” while Paragraph 3 lays the foundation for a strict secular regime: “The State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity.” Article 89 complements these clauses through a ban on expending public money for “the use, benefit or maintenance of any religious institution or association.” When the new constitution came into effect on May 3, 1947, it signaled the end for official state patronage of Shinto shrines.

Although the text prohibits state actors from participating in any “religious activity,” it offers little guidance as to how “religious” is to be understood in this context.

It is important to note that while Articles 20 and 89 rely on the category of religion, they do not provide a definition of the concept. For instance, although the text prohibits state actors from participating in any “religious activity,” it offers little guidance as to how “religious” is to be understood in this context. This is also the case in the major law which complements the constitution in regards to religion: the Religious Juridical Persons Law. Originally written during the occupation by a workgroup made up of representatives of the government as well as various religious actors, the law came into effect on April 3, 1951. Unlike the constitution, which despite being written by a foreign power has never been revised, the Religious Juridical Persons Law has been amended on several occasions, most recently in 2019. This law provides the general framework for how organizations can be registered as religious juridical persons in Japan, including stipulations on what they can and cannot do.

While the Religious Juridical Persons Law also does not define religion as a general concept, it establishes that the term “religious organization” as found in the constitution should be understood to mean a formally registered religious juridical person. Although any organization fulfilling certain criteria can technically be registered as a religion, the terminology used in the law suggests that Christianity, Buddhism, and Shinto should be viewed as the three basic models for how a religion can be organized. Since the enactment of the law, a huge number of organizations, congregations, and individual shrines and temples have been registered under the Religious Juridical Persons Law. As of 2019, there were more than 180,000 religious juridical persons in Japan, of which 47% were registered as derived from Shinto, 42% as Buddhist, and 2.5% as Christian, with the rest registered under the miscellaneous category of “various teachings.” Under “various teachings” we find not only a number of new religious organizations but also other established religions, such as the Japan Muslim Association.

The fact that neither the constitution nor the Religious Juridical Persons Law provide a working definition for how religion is to be understood has ensured that this task is placed in the hands of the Japanese judiciary. It is interesting to note that, unlike in the American and European contexts where the question of how to define religion in law is often raised in cases centered on religious freedom legislation, in Japan such cases rarely try the limits of the concept of religion. One explanation for this could be the strong focus on individual rights in general present in the Japanese constitution. Besides the guarantee of religious freedom, the constitution guarantees its citizens a number of fundamental rights as long as these do not violate “the public welfare” (Article 13), including freedom of conscience (Article 19) and freedom of expression (Article 21). This allows Japanese courts to easily circumvent the question of whether an action was motivated by religion simply by emphasizing other rights. An example of this was the Jehovah’s Witnesses Blood Transfusion case, resolved by the Supreme Court in 2000, in which a believer had been subjected to a blood transfusion during surgery against her clearly stated wishes. Although the subject of her religious belief was discussed in court, the case was resolved in favor of the plaintiff by reference to the fundamental principle of informed consent.

Ōichi Shrine in Tsu, Mie prefecture. Image Courtesy of Author.

While there have been several significant rulings on the principle of religious freedom in Japanese courts, the question of how to understand religion as a legal category is more commonly debated in cases concerned with state-religion relations. Rather than involving individuals who claim that what they do should be considered religious, these cases typically feature one party either denying their status as religion or, more commonly, that what they did was religious. These are what I call the “secularism cases,” cases that primarily deal with the third paragraph of Article 20. These cases center around the question of how to interpret “religious activity,” and a number of them have been resolved by the Supreme Court. In these cases we often see a conflict between those who adhere to the view that Shinto is something beyond the category of religion and those who consider it a religion like all the others. If we look at those secularism cases that have reached the Supreme Court, they all deal with representatives of the Japanese state who have in one way or another interacted with a Shinto institution, and in all of these cases they are brought to court by people who for various reasons want to distance themselves from the ideology of the prewar Japanese state. More often than not, the plaintiffs in these cases come from or are represented by actors from religious organizations, for instance Shin Buddhism or Christian denominations.

The fact that neither the constitution nor the Religious Juridical Persons Law provide a working definition for how religion is to be understood has ensured that this task is placed in the hands of the Japanese judiciary.

The arguably most significant ruling on state-religion relations in postwar Japan was handed down by the Supreme Court in 1977, when the Tsu Groundbreaking Ceremony case was resolved through a grand bench landmark decision. The original complaint had been filed in 1965 by a member of the local government in the city of Tsu in Mie Prefecture, after the mayor of Tsu had used public funds to finance a groundbreaking ceremony (jichinsai) at the start of the construction of a new public gymnasium. The ceremony was presided over by priests from the nearby Ōichi Shrine and was conducted in accordance with Shinto practice. The plaintiff in the case, who was a representative for the Japan Communist Party in the city council, argued that the mayor had violated the principle of secularism as established by the constitution, as in his eyes this was clearly a case of “religious activity.” The plaintiff also claimed that he had been pressured into participating in this ceremony, something which caused him, an avowed atheist, to suffer “mental anguish.” It is worth noting that claims to personal stakes in a case are necessary, as the Japanese judiciary cannot decide on a case unless the plaintiff has a personal interest in the matter.

The defendants in the Tsu Groundbreaking Ceremony case rejected all the plaintiff’s claims, including the fact that he had been forced to partake in the rituals. When countering the claim that the groundbreaking ceremony constituted a religious activity under the constitution, the defense presented an elaborate argument for why such rituals should not be considered religious. The defense argued that religious activity is an activity that seeks to spread “religious doctrine” or to promote the “indoctrination of believers.” This definition is taken from the definition of a “religious organization” as found in the Religious Juridical Persons Law, where it is used as a guideline for deciding what organizations can register under the law. The defense ignored the fact that Ōichi Shrine, like most Shinto shrines, was in fact registered as a religious juridical person, and instead argued that specific rites such as groundbreaking ceremonies did not attempt to spread religious teachings, and consequently should not be considered to be religious activity. Essentially, certain rituals that have existed “in our country since ancient times” might transcend the limits of religion and should instead be viewed as “customs” or “social rituals.”

The first instance ruling was handed down in 1967 by the Tsu District Court. The three judges of the court dismissed the plaintiff’s case, concluding that the groundbreaking ceremony had been a private event and that the mayor had simply invited members of the local government to participate. The court also dismissed the idea that a groundbreaking ceremony could be seen as a religious activity by presenting a normative definition of religion followed by an evaluation of why the ceremony in question did not match this definition. The argument, though too long to reiterate here, essentially followed the pattern presented by the defendant: these rites represented traditions carried over from ancient times; they did not represent a specific religious teaching; and to conduct them should not be seen as an attempt to spread religion, but rather as an expression of customary acts commonly carried out in Japan. Religion was equated with formal teachings – that is, modelled on the accepted prewar religions Buddhism and Christianity – whereas the rituals carried out by Shrine Shinto actors were considered to be more in line with tradition or culture.

The plaintiff appealed to the Nagoya High Court, which in 1971 overturned the first instance ruling. The judges of the high court expressed concerns about the ambiguous nature of the term “religion,” noting that it was pluralistic and difficult to define in a proper way. In their definition of the concept, they suggested a broad understanding of religion which would include both private and public aspects of religion, as well as religions with and without a clear founder. This last aspect is significant, as the lack of a founder is often emphasized by those who argue that Shinto is essentially different from other religions. To decide whether something was to be understood as a “religious activity” under the constitution, the judges introduced a three-stage evaluation which sought to establish the status of the host institution, the activity’s eventual basis in religious practice, and the extent to which the act was received with discomfort by common people. The last stage is particularly interesting, as it reflects the judges’ attempt to interpret the constitution with the best interest of minorities in mind, in contrast to the pre-1945 system of compulsory shrine rites. Based on their method of evaluation, the court found that the ceremony in question was indeed religious, and that the public support of a Shinto groundbreaking ceremony was therefore a violation of Articles 20 and 89 of the constitution.

The defendants appealed the high court ruling to the Supreme Court, which handed down its ruling on July 13, 1977. The case was resolved by a grand bench, meaning that all fifteen justices of the Supreme Court took part in the decision. The Supreme Court decides on most cases through three petty benches of five justices, but when a case is of particular principal importance, a grand bench is called. Through the majority ruling the Supreme Court overturned the high court decision, with five justices signing dissenting opinions. Unlike the judges of the high court, who had emphasized the importance of accommodating diversity and the feelings of minorities, the Supreme Court justices instead sought to establish a precedent whereby some cultural and traditional practices could be permitted while still upholding the “religious neutrality” of the state. Discarding the three-stage evaluation used by the high court, the Supreme Court instead introduced the “object and effects standard” through which any given act could be tested:

With regards to the evaluation of whether an act corresponds to … religious activities or not, this cannot be fully understood [by asking] whether the host of the act is a religionist or not, whether the procedure of the act … conformed to rules decided by a religion, or [by examining] the external aspects of the act, but must be decided objectively and in accordance with common sense by taking into account various circumstances [including] the place where the act is carried out, the religious assessment of the act by common people, the intention and object of the actor in carrying out the acts as well as whether and to what extent there existed a religious consciousness, and whether the act would have any effect or influence on common people.

The object and effects standard is sometimes described as an equivalent of the Lemon test, and it has been used in most subsequent rulings on state-religion relations as the primary method for interpreting Articles 20 and 89 of the constitution. Unlike in the high court ruling, where the judges consistently emphasized Japan’s prewar history of oppression of religious minorities and the importance of listening to minority voices in cases such as this, the object and effects standard is fully based on the opinions of an assumed “common people” (ippanjin). Designed so as to align with majority behavior, the standard opens the door for courts to grant certain leeway to rites and rituals which can be argued correspond to how “normal” Japanese people act. In the Tsu Groundbreaking Ceremony case, the justices used the standard to conclude that common people in Japan did not consider groundbreaking ceremonies to be religious, deeming the rituals conducted by the priests from Ōichi Shrine to have been a form of “secular events.” Essentially, just because the actor carrying out a ritual is registered as a religious juridical person belonging to one of the three major religious traditions present in Japan does not necessarily mean that the ritual itself is to be considered a “religious activity.”

Ehime Gokoku Shrine, Matsuyama prefecture. Image courtesy of author

Although the object and effects standard introduced by the Supreme Court in 1977 remains the predominant method for interpreting the constitutional principle of secularism in Japan, the Supreme Court ruling on the Ehime Tamagushiryō case in 1997 introduced a modification to the precedent which has since proved a challenge for those who favor a closer relationship between Shinto and the state. The case originated in a series of complaints filed in the 1980s against the governor of Ehime Prefecture. The governor, who also served as chair of the local branch of the Japan War-Bereaved Families Association (Nippon Izokukai), had for a number of years used public money to pay for offerings made to the spirits of local fallen soldiers both at the Gokoku Shrine in the city of Matsuyama and at Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. While the governor considered this to be a form of courtesy shown to those who gave their lives for the nation, the plaintiffs argued that this was a clear violation of Articles 20 and 89. The issue was particularly sensitive since it involved the question of how to mourn the more than two million men who died during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II. While many people in Japan view Yasukuni Shrine and its affiliate shrines as symbols of a militaristic prewar regime that brought death and destruction to Japan and other Asian countries, others see these shrines as central to the process of mourning and honoring those who died for the nation. Amongst those who favor the latter view is former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, the last prime minister to date to visit the shrine.

The first and second instance rulings in the Ehime Tamagushiryō case illustrate the inherent problems with the object and effects standard, as this standard, like the text of the constitution itself, relies on a shared understanding of religion. In their 1989 ruling, the Matsuyama District Court found that the offerings made at the two shrines were religious in nature and that they served to support and aid the religious activities of specific religious actors. Based on the object and effects standard, the judges concluded that the prefectural governor had violated the ban on public actors engaging in religious activity as stipulated in Article 20, as well as Article 89’s ban on expending public money for the benefit of religious organizations. However, this ruling was overturned by the Takamatsu High Court in 1992, who used the same object and effects standard to reach the opposite conclusion. The judges of the high court argued that the governor’s activities were not religious but political, as they had been carried out with the intention of pleasing one of his most important support bases – local war-bereaved families. Furthermore, the sum of money expended to the shrines was deemed too insignificant to count as public support for religious institutions and was consequently considered to be merely symbolic in meaning. While the judges did not deny that the offerings might have had some connection to religion, they found this connection to be too diminutive for the rites to be considered religious by “common people.” Yasukuni Shrine was presented as a place where a majority of Japanese people go to commemorate those who died in war, and offerings made at the shrine should simply be considered a form of “social ritual.”

The high court ruling on the Ehime Tamagushiryō case was appealed by the plaintiffs to the Supreme Court, where it was resolved through a grand bench ruling handed down on April 4, 1997. The Supreme Court justices completely overturned the high court ruling, in a majority ruling that again relied on the object and effects standard. Echoing the 1977 ruling on the Tsu Groundbreaking Ceremony case, the justices of the Supreme Court argued that the constitution should be interpreted as establishing the “religious neutrality” of the state rather than forcing a complete distancing from religion, since this was in reality an impossibility. The state must be able to deal with religious organizations when the need arises – for instance, in cases where national cultural properties happen to be owned or run by a religious organization – but public actors must also refrain from giving preferential treatment to certain religious institutions. The justices noted in the majority ruling that this was a difficult balance to maintain, but key to this was a fair use of the object and effects standard. According to the justices behind the majority opinion, the 1977 ruling had been correct in assessing that a groundbreaking ceremony would not necessarily constitute a religious activity, as this was a common traditional practice carried out by most actors when initiating a construction project, but the offerings made at Yasukuni Shrine and Ehime Gokoku Shrine clearly overstepped the boundaries of “social ritual.”

The secular rites of prewar Japan continue to exist in a precarious territory, contested by actors with fundamentally different ideas about how to make sense of Japanese identity.

Unlike in the ruling on the Tsu Groundbreaking Ceremony case, the justices in the Ehime Tamagushiryō case emphasized the legal status of the institutions involved. The fact that these shrines were both religious juridical persons meant that the governor of Ehime Prefecture had maintained a special relationship with a specific religious organization – something which is clearly prohibited by the constitution. Rather than evaluating the “religiousness” of the offerings or the rites carried out at the shrines, the Supreme Court ruling suggests that any activity carried out at a religious organization should be considered religious under the constitution. This is to some extent a way to evade the issue of having to define “religion” as a legal category, albeit one that is not used consistently even by the justices behind the majority opinion. The interpretation of Articles 20 and 89 in the majority ruling was still based on the object and effects standard, which meant that the “religious assessment” of “common people” had to be considered. The court’s decision therefore rested both on the objective legal status of the institutions involved and on how they perceived “common people” to judge the offerings made at the two shrines, thus opening up for a continued reliance on subjective evaluations made by the courts. This was criticized by Justice Takahashi Hisako in her complementary opinion:

While the first instance ruling and second instance ruling both argued based on the same object and effects standard, their conclusions were the opposite, and even in this ruling, the majority opinion and the dissenting opinions, while acknowledging the same facts and depending on the same object and effects standard … have reached completely opposing conclusions. Considering this, it is irresistible to doubt whether the standard shown in the Tsu Groundbreaking Ceremony case can be used as a clear guideline.

While it did not signal a complete departure from the previous method for interpreting the principle of secularism in postwar Japan, the Ehime Tamagushiryō case suggests a move towards a stricter separation of Shinto institutions from the public sphere. A number of significant lawsuits on state interaction with Shinto have been resolved by the Japanese judiciary since 1997, and while they have not always been resolved in favor of the plaintiffs, there has been a clear move away from the idea that Shinto rites should be given a special leeway based on their status as custom and tradition. This has led to an increase in political activity amongst those actors who champion a closer relationship between Shinto and the Japanese state, something which is manifested in the involvement of Shinto actors in the campaigns to revise the Japanese constitution. Since the “social rituals” of the state are no longer tolerated, the only solution is to rewrite Articles 20 and 89. It is worth noting here that those published drafts which include revisions to these articles, such as the 2012 draft produced by the Liberal Democratic Party, do not question the idea that “religion” should be fully separated from the state. They are merely critical of how the category is currently interpreted by the Japanese judiciary.

The process of religion-making remains ongoing in Japan. Despite its brief history in the Japanese vocabulary, religion as a category has already undergone several iterations. Originally used to denote alternative beliefs tolerated by the Japanese state, it was reforged after 1945 as a category to give all those practices that the occupation authorities deemed religious a shared common ground. Since the occupation ended in 1952, the category has been the subject of constant negotiations and reinterpretations, in political discourse as well as in courts of law. Winnifred Sullivan’s argument that “after disestablishment, law has no way of constitutionally locating religion” is as true about Japan as it is about the United States. The secular rites of prewar Japan continue to exist in a precarious territory, contested by actors with fundamentally different ideas about how to make sense of Japanese identity. ♦

Ernils Larsson holds a PhD in the history of religions from Uppsala University, Sweden. His research focuses primarily on the politics of religion and law in Japan. Larsson is currently a visiting researcher at the Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies at Lund University.

Recommended Citation

Larsson, Ernils. “Religion-Making in Japan’s Courts of Law.” Canopy Forum, November 24, 2020. https://canopyforum.org/2020/11/24/religion-making-in-japans-courts-of-law/