The Reckoning of Religious Studies and Colonialism

Laura Ammon

Photo by rolf neumann on Unsplash.

The study of religion has a long history of service to Western imperial ambitions. Recent decades have seen religious scholars wrestle with the implications of this colonial legacy for the future of the field. This essay, divided into two parts, will explore the connections between religion and colonialism. First, I will give a brief history of the role of Christianity in the colonial expansion of western European powers. This relationship between empire building and religious missionizing formed a legacy that continues to shape our world today, a legacy labeled by Aníbal Quijano (2007) as “the colonial matrix of power.” Religion forms a significant component of this matrix. Second, I will discuss the relationship between colonialism and the study of religion.

Colonial Expansion in the History of Christianity

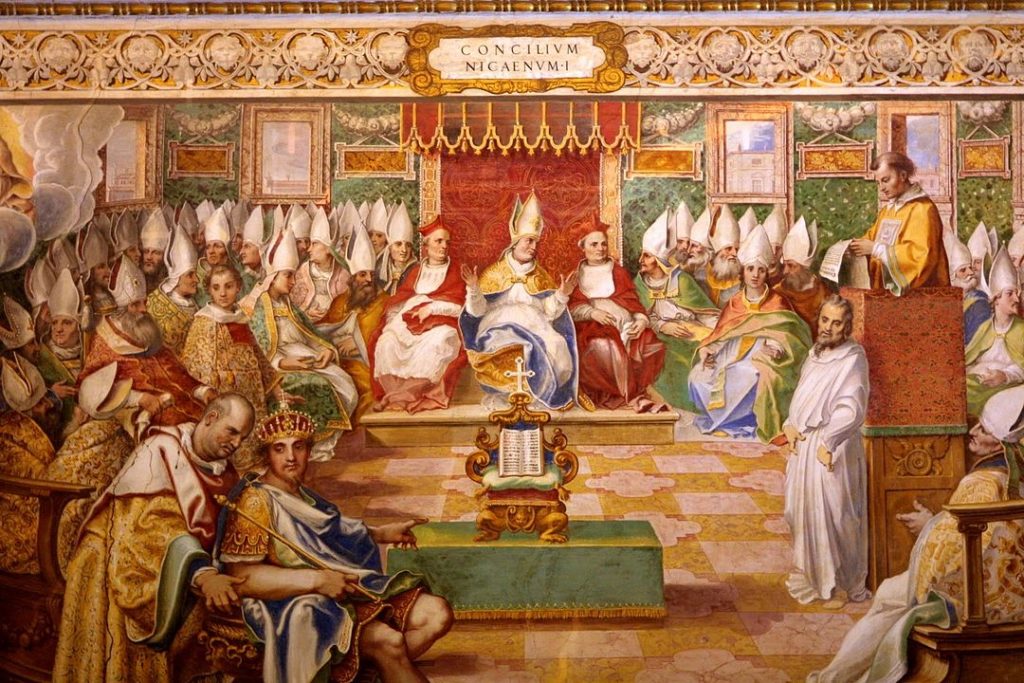

Christianity’s relationship with empire building and colonization originates, at least in part, in its development in the fourth century from a loosely connected collection of devotional sects to the religion of the empire. After Constantine recognized Christianity as a legitimate religion in the Roman Empire, the Council of Nicea (325 CE) instituted the official Christian church, which grew in power through the further solidification of its status as the state religion in 380 CE. Through this developing hierarchy, theologians began to establish the criteria for orthodoxy, orthopraxy, and heresy, organizing ecclesiastical structures to reinforce rapidly solidifying boundaries. As Christianity spread throughout Europe, it brought along certain cultural expectations of God’s realm on earth. The next 1,000 years were spent striving – and failing – to build a unified Christendom. Ireland and Germany forged their own Christianities in the middle ages through their colonial encounters with the expanding reach of Christianity, and that pattern has continued.

Christianity did not lack competition. The rise of Islam beginning in the seventh century, in the middle east Holy land, Asia, and also in Spain (Iberia) and northern Africa, challenged the idea of a hegemonic Christendom. To this end, the Discovery Doctrine, a papal decree initially developed as part of the Crusades, denied the Muslim claim to Jerusalem and gave Crusaders authority to seize those lands and assets. A colonial Christendom was further expanded in 1455 by Pope Nicholas V in the bull Dum Diversas, which granted Portugal the right to seek out, “capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans” as well as “enslave them in perpetuity” in order to bring humankind under the umbrella of Christianity (Stam and Shohat). The Spanish quest to vanquish Islam from the Peninsula brought the crusade into Europe and exacerbated the question of how to govern and maintain a global Christendom.

Council of Nicaea 325 from Wikimedia. (PD-US).

As a result of the success of the Spanish reconquest and the discovery of the New World, in 1493 Pope Alexander VI divided the world across the Atlantic Ocean in the bull Inter caetera, granting the Spanish monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand rights to all lands to the west of the Azores and south of the Cape Verde islands. While scholars disagree about precisely what type of legal grant Alexander VI issued, it is clear the Spanish monarchs took it as a license to claim land and people across the sea for Spain and Christianity, seeing the new territory as a rightful expansion of their Christian empire beyond the Peninsula and Europe. Monarchs, conquistadors, and missionaries saw the success of the reconquest of Spain as a clear sign of their providential role in the Christianization of the New World. Though this connection between empire-building and Christianity was not new, it would be executed in a novel combination in the New World encounter.

In the context of the expansion of Europe across the Atlantic, the Requirement (Requerimiento) was the central theological doctrine and legal justification of the conquest. This document was read to natives to legitimate and certify Spanish claims to land and inhabitants. Indigenous peoples were informed of the (new) order of humanity: the conquistador who read the Requerimiento was acting as the voice of God’s authority on earth, the Pope. This was not the soldier demanding indigenous persons submit to European conquerors, it was God commanding indigenous people to convert to Christianity or suffer total warfare. This colonial ultimatum, carrying the thinly-veiled threat of violence, is characterized as “convert or die.” This “choice” was presented with the conviction that the ultimate authority behind the seizure of land, culture, and human lifeways was the supreme God who had created all of heaven and earth. Colonialism and conquest had divine authorization.

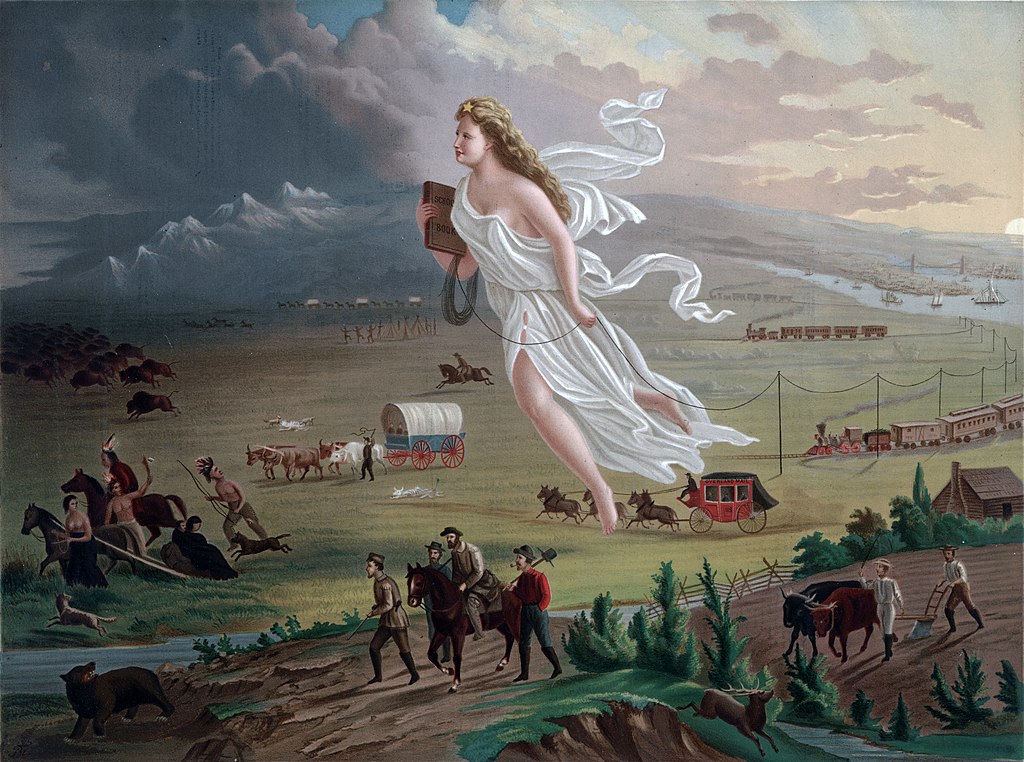

The discovery doctrine was carried forward into the U.S. colonies and eventually became the foundation of Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine through a series of early nineteenth-century SCOTUS cases known as the Marshall Trilogy. These cases decreed that the title to lands belonged to the people who “discovered” it, ruling that Native Americans did not – and could not – own the lands claimed by European settlers. Along with the Dawes Act, these statutes have since contributed to Federal Policy regarding Native American Land rights.

American Progress by John Gast. (PD-US).

Reservations are lands “given” to Native Americans by the Federal Government, usually in exchange for their relinquishing claims to tribal homelands. Some of the Native American lands are held in trust by the U.S. Government. While not reservations per se, they are still considered Native lands. As part of the U.S. Government trust for native lands, tribal lands are subject to the will of the U.S. Government plans for redistribution, repurposing, or reallocation. Prior to 1968, Native Americans living on reservations did not enjoy the basic civil rights guaranteed to other U.S. citizens. Only with the passage of the Indian Civil Rights Act were reservation residents offered full United States citizenship.

Since much of the land Native Americans hold sacred either constitutes part of a trust or a public National Park, conflicts over land use frequently arise. Native American religious observation often clashes with federal policies, such as in the construction and use of sweat lodges, holding multi-day vigils in national parks, or sacrificing federally protected animals such as the bald eagle for religious and ritual purposes. The 1994 American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) is a non-binding resolution that recognizes the Free Exercise of Religion Clause applied to Native American religious practices. The Act does not include penalties for federal or private agencies for failing to comply with its mandates. However, AIRFA has given Native Americans solid legal ground to fight battles over religious freedom and their ability to preserve, protect, and continue their religious and cultural heritage.

Many scholars have discussed the connection between colonialism and globalization, particularly in the context of Latin American environmental exploitation, arguing the Catholic church’s role in colonialism established the “ideological foundations of globalization” that continues to affect indigenous peoples, their lifeways, the environment, and climate change (Lorentzen and Salvador 2006). In December 2015, the Third International Rights of Nature Tribunal established themselves in Paris during the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This grassroots response to the continuing legacy of colonialism consists of indigenous political and religious leaders, legal authorities, and lawyers, in addition to lay persons from around the world. Mandated by the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, the tribunal “provides a systematic alternative to environmental protections, acknowledging that ecosystems have the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate their vital cycles” (tribunal website). The Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth is currently under consideration as part of the United Nations General Assembly Harmony with Nature Report.

Colonialism and the Academic Study of Religion

The problematic colonial history of the very category of “religion” challenges the idea that religion exists somehow separately from culture. Because the ways in which “religion,” “religious,” or “religions” are defined often determines the arena of study, that defining must be done with an intention that recognizes the possibility of undermining any previous understanding of “religion” itself (Smith 2004). The classification of religion, religions, and/or religious, similar to the classification of race, was redefined in the context of the expansion of European economies into China, India, and the larger western hemisphere of the Americas. Since “religion” had previously only been invoked as a term that encompassed the Abrahamic traditions and contrasted with “paganism,” the European realization that the lands of both the east and the west had other notions of religion led the founders of the academic study of religion to define the term to fit a normative set of parameters that closely parallel Christianity. These parameters shifted considerably as the Protestant English and Dutch empires eclipsed the Catholic Spanish and Portuguese empires through the seventeenth century, ultimately leading to a Protestant bias in the discipline, though still retaining the supportive politics of the Doctrine of Discovery and settler colonialism.

The problematic colonial history of the very category of “religion” challenges the idea that religion exists somehow separately from culture.

The study of religion was considered one of the branches of colonialism, particularly in the context of both “understanding” and “classifying” indigenous traditions. The “quest for precontact purity” was an effort to categorize and classify religions in evolutionary stages of development between “savagery and civilization” in order to understand the remote history of humanity on its climb to civilization and the modern world (Chidester 2014). The categories of “savage” versus “civilized” were grounded in racial as well as religious differences. This categorization also upheld an idea of preserving soon-to-be vanished or extinct religions of humankind for posterity as all the peoples of the world were brought into the Enlightened world of Western modernity through colonial expansion. But this preservationist stance ultimately did not elide the destructive nature of the colonialist study of religion, as modern critics have often pointed out: “The enduring presence of indigenous America looms behind many cultural debates, posing questions about the very legitimacy of colonial-settler states” (Stam and Shohat 2012).

Walter Mignolo has argued that the foundations of modernity and global capitalism in the world today are grounded in the legacy of the Christian colonialism of the late fifteenth century with the discovery of the New World, rather than in the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. He contends that the birth of the modern world “can be described in conjunction with the emergence of the Atlantic commercial circuit […]” and its subsequent displacement of indigenous American peoples and enslavement of African peoples (2008). The comparative study of religion finds itself at the forefront of marking differences between “true religion” and so-called pagan or diabolical rites and practices. The Discovery Doctrine and the Requiremiento were legal proclamations that authorized the Christian expansion, yet that expansion was facilitated by missionaries who sought to convert indigenous peoples. Some of these missionaries were hoping to understand aspects of the indigenous cultures; others were hoping for a new millennial world; still others sought utopia. Regardless, all pursued the converting of souls for Christianity and the incorporation of indigenous peoples into the Spanish Empire. These missionaries, such as Bernardino de Sahagún, who collected the Florentine Codex, were the first to chronicle indigenous religious practices, developing methods for categorizing the diversity of practice and belief that were being suppressed by the same missionaries actively enforcing the spread of Christianity. New World missionaries produced seminal texts that classify and maintain differences that would become foundational for the academic fields of History, Religious Studies, and Anthropology, even while they still strived to contribute to the spread of the Christian empire – to the detriment of native peoples.

Just as natural resources from colonies were used to manufacture goods and services for European consumers, so were the religious resources mined from the colonial project used to produce knowledge of the “exotic,” “savage,” and “barbarous” religions of non-Western, non-Christian peoples.

David Chidester traces this work further through the British Empire, linking the development of comparative religion as a field to study to the colonial project, arguing that African, Indigenous American, and South Asian religions were the intellectual “raw materials [that] had to be extracted from the colonies, transported to the metropolitan centers of theory production, and transformed into the manufactured goods of theory that could be used by an imperial comparative religion” (Chidester 2014). Just as natural resources from colonies were used to manufacture goods and services for European consumers, so were the religious resources mined from the colonial project used to produce knowledge of the “exotic,” “savage,” and “barbarous” religions of non-Western, non-Christian peoples. The legacy of these actions remains in the bricolage of religious ideas, practices, and thought wrapped together from native and Christian traditions and reappropriated and commercialized in the modern American field of religious studies, as well in as the overall religious marketplace of new age, new religious movements and eastern spirituality.

Recent scholarship has taken seriously the legacy of colonialism in the study of religion on both the academic and pedagogical front. To take seriously the role of religion in having created structures of oppression means that the field must acknowledge its contribution to the colonial legacy. “Thus, to study religion is not to study a ‘thing’ in itself, which exists across humanity as a universal. It is instead a study of how particular ideas (and discourses) of ‘religion’ are practiced and operationalized in various contexts” (Nye 2019). Too often those ideas have been in service of exploitation. The field of religious studies needs to seriously reckon with its colonial past in order to reflect the world of ritual, belief, and thought of native peoples. ♦

Bibliography

Chidester, D 2014. Empire of Religion: Imperialism and Comparative Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226117577.001.0001

Mignolo, Walter D., 2008. “The Geopolitics of Knowledge and Colonial Difference,” in Coloniality at Large: Latin America and the postcolonial debate, eds. Enrique Dussel Mabel Morana, and Carlos A. Jauregui (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2008), 229.

Nye, M., 2019. Decolonizing the Study of Religion. Open Library of Humanities, 5(1), p.43. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/olh.421

Quijano, Aníbal, 2007. ‘Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality’’. Cultural Studies, 21(2): 168–178. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353

Smith, Jonathan Z. 2004. Relating religion: essays in the study of religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stam, Robert, Shohat, Ella, 2012. Race in Translation: Culture Wars Around the Postcolonial Atlantic. NYU Press.

Laura Ammon is Associate Professor of Religion at Appalachian State University in Boone, NC. She has published on the history of the comparative study of religion and on the role of sixteenth-century missionary documents in the development of theories of religion. She is co-author of Religion in Sixteenth-Century Mexico: A Guide to Aztec and Catholic Practices with archaeologist Dr. Cheryl Claassen forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.

Recommended Citation

Ammon, Laura. “The Reckoning of Religious Studies and Colonialism.” Canopy Forum, March 19, 2021. https://canopyforum.org/2021/03/19/the-reckoning-of-religious-studies-and-colonialism/