The Global Pandemic and

Government “COVID-19 Overreach”

P. T. Babie

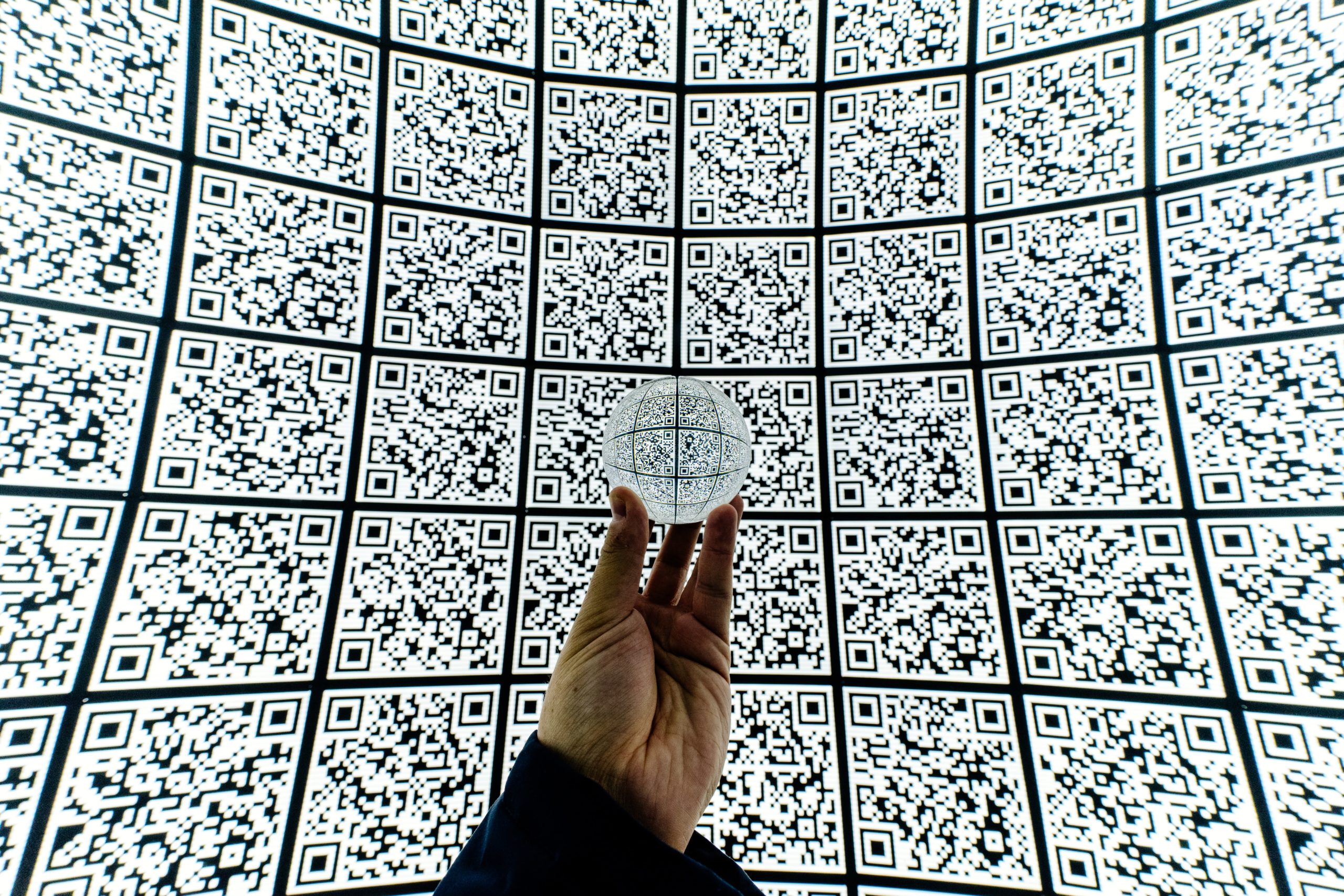

Photo by Mitya Ivanov on Unsplash.

This article is part of our “Law and Religion Under Pressure: A One-Year Pandemic Retrospective” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

March 11, 2021 marked the first anniversary of the World Health Organization declaring COVID-19 a global pandemic. During this past year, a staggering 118,268,575 people contracted the virus, while 2,624,677 have died. As the world came to terms with the implications of this international public health crisis, governments the world over imposed restrictions on all forms of public life, including public communal worship. In an early assessment of those restrictions on the free exercise of religion, Charles Russo and I wrote that:

It matters…that we understand the value of protecting fundamental rights, expecting judges to utilize a framework which makes possible the careful balancing of competing interests. Citizens must always lead by example. Doing so means knowing when to curtail our own rights when necessary to protect the general welfare. It also means retaining more than a passing interest in the ways in which governments restrict fundamental freedoms like religious freedom, and the justifications they offer for doing so. Otherwise, we may soon find that ‘if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us at night.’1 citing James Baldwin, An Open Letter to My Sister, Angela Y. Davis in If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance 19, 23 (Angela Y. Davis, Ruchell Magee, The Soledad Brothers and Other Political Prisoners (Eds.), repr. 2016).

We were concerned that restrictions aimed at the free exercise of religion might, over time, expand to limit other fundamental rights and freedoms in the effort to control the spread of the virus. Of course, we recognized the very real need to limit public gatherings, ultimately concluding that in order to address the public health crisis, governments may justifiably take measures aimed at achieving that end.

In some cases, COVID-19 restrictions may prove valuable in the longer term. In California, for instance, the Chief Justice recently called on the state to retain permanently a number of reforms put in place in response to COVID-19. Such measures may be both a justifiable response to the pandemic and a valuable reform of the judicial process once the public health threat has passed.2See Rachel Rippetoe, Let’s Keep Some COVID Court Fixes, Calif. Chief Justice Says, Law360Pulse(March 15, 2021) <https://www.law360.com/pulse/articles/1364864/let-s-keep-some-covid-court-fixes-calif-chief-justice-says>.

But our apprehension was not limited merely to those instances in which a government may justifiably restrict or limit the free exercise of religion, or other fundamental rights and freedoms, in ways which may prove useful either to combatting the pandemic or in reforming public life. Rather, we worried that initially acceptable measures might serve as the first step towards other unjustifiable reforms on the basis of responding to the public health crisis, and which may infringe or deny a number of fundamental human rights and freedoms, most notably freedom of movement and association; education; work; and privacy. As we predicted, governments have done just that.

We worried that initially acceptable measures might serve as the first step towards other unjustifiable reforms on the basis of responding to the public health crisis, and which may infringe or deny a number of fundamental human rights and freedoms, most notably freedom of movement and association; education; work; and privacy.

The Australian state of South Australia recently attempted to enact legislation “that would permanently enshrine COVID-19 pandemic provisions in [South Australian] law,” including making provisions for “the rights of [public] officers to exercise any power or function even if doing so contravened existing state laws, or “affected the lawful rights or obligations” of any SA citizen.” That is the very sort of government “COVID-19 overreach” of which Professor Russo and I warned in March 2020. To widespread relief, the South Australian government ultimately backed down, and has since proposed a revised version of the bill that would not so readily contravene fundamental rights and freedoms. Still, a number of concerns about other forms of COVID-19 overreach have been raised by members of the Australian community.3See, eg, Human Rights Law Centre, COVID 19 Response <https://www.hrlc.org.au/covid19-response>. In this brief essay, I look at two Australian examples, one already widely used, the other likely to be very soon, and both of which hold significant concerns for personal liberty: contact tracing through the use of Quick Response (QR) codes, and vaccine travel passports.

Quick Response (QR) Code Contact Tracing

Quick Response (QR) codes are similar to barcodes, containing information which triggers a smartphone to perform an action, such as visiting a website or an app. Throughout 2020, every state and territory government in Australia began to use QR technology to allow for contact tracing by collecting relevant data for public health officials. In the state of New South Wales, for instance, “digital collection of patron data became mandatory for most…businesses including cafes, pubs, function centers, amusement centers and entertainment venues. Because data must be collected digitally (not via pen and paper), many of these venues began using QR codes.”4Sonia Hickey, Federal government agency issues warning about QR codes, mondaq (January 14, 2021) https://www.mondaq.com/australia/data-protection/1025604/federal-government-agency-issues-warning-about-qr-codes. Such codes can either be created by a government agency, such as the Services NSW app, or by a private entity, such as a restaurant or café.

Two human rights concerns arise with the use of QR codes, whether they are generated by a government agency app or by a private entity. First, the data may be open to misuse through sharing by a private, or even public, entity. And, second, even in the case of a public entity, such as the Services NSW app, there are no guarantees of security. “In 2020, [for instance,] more than 50,000 Australian driver license holders had their personal data uploaded to, and left exposed in open cloud storage.”5Sonia Hickey, Federal government agency issues warning about QR codes, mondaq (January 14, 2021) https://www.mondaq.com/australia/data-protection/1025604/federal-government-agency-issues-warning-about-qr-codes. Thus, “no matter how good cyber security is, data is still vulnerable occasionally to an error leading to a security breach, malicious data fraud, or hackers.”6Sonia Hickey, Federal government agency issues warning about QR codes, mondaq (January 14, 2021) https://www.mondaq.com/australia/data-protection/1025604/federal-government-agency-issues-warning-about-qr-codes.

The fact that South Australia, which uses its own QR code contact tracing system7Government of South Australia, COVID Safe Check-In <https://www.covid-19.sa.gov.au/restrictions-and-responsibilities/covid-safe-check-in>. For a full list of all Australian state and territory QR code contact tracing requirements, see COVID Comply Australia, Professional contact tracing for businesses and governments <https://covidcomply.org>., was willing to allow public officers vast powers — notwithstanding the fundamental rights of citizens with respect to personal liberty — ought to give cause for concern about the security of the data compiled using QR codes, and the uses to which it is put by both private and public entities. The real concern, as Charles Russo and I suggested in March 2020, is not so much with the use of QR codes for contact tracing in addressing COVID-19, but in their ongoing use to track the justifiable movement of citizens long after the pandemic has been controlled.

Vaccine Passports

A number of countries — the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Israel, and Australia, as well as the European Union — are currently studying the implementation of vaccine passports as a means of bolstering and encouraging the ongoing vaccination program underway globally.8 Needle to know: How useful are vaccine passports?, The Economist (March 13, 2021) <https://www.economist.com/leaders/2021/03/13/how-useful-are-vaccine-passports?>; Amy Maguire, Fiona McGaughey & Marco Rizzi, Can governments mandate a COVID vaccination? Balancing public health with human rights–and what the law says, The Conversation (November 30, 2020) <https://theconversation.com/can-governments-mandate-a-covid-vaccination-balancing-public-health-with-human-rights-and-what-the-law-says-150733>. Passports would allow travel, being “most useful in the period when large numbers of people who want to be inoculated risk being infected because vaccine is scarce [sic].”9Needle to know, supra n 15. Those who support their use argue that passports operate as an incentive to be vaccinated.10Ibid; Maguire, McGaughey & Rizzi, supra n 15.

And yet, from a human rights perspective, we ought to be wary, not for what vaccine passports might make possible while the pandemic continues, but for what it might allow governments to do once the threat of a public health crisis has passed.

And yet, from a human rights perspective, we ought to be wary, not for what vaccine passports might make possible while the pandemic continues, but for what it might allow governments to do once the threat of a public health crisis has passed. As with QR code contact tracing, passports may be a threat to personal data and allow for the state to intrude into its citizens’ general health. More alarmingly, used as an incentive for vaccination, they may become oppressive: “If you need one simply to get on a bus or buy a loaf of bread, you lose your choice to be vaccinated.”11Needle to know, supra n 15. As with QR codes, the possibility for COVID-19 overreach with vaccine passports is significant.

Should we remain vigilant?

Charles Russo and I warned at the start of the pandemic that we ought to ‘retain[] more than a passing interest in the ways in which governments restrict fundamental freedoms like religious freedom, and the justifications they offer for doing so.’ Our reason: because that was merely a first step towards limiting other personal freedoms as part of controlling the spread of COVID-19. That objective is, of course, an entirely justifiable reason for limiting fundamental human rights. But the justifiability of these limitations does not obviate the need to ensure that what is justifiable now does not become unjustifiable in the future.

QR Code contact tracing and vaccine travel passports may seem a small price to pay when the pandemic rages. We must not allow our attention to be diverted from this fact by the very real threat of the pandemic for our health. Yet both raise serious human rights concerns in the long term. This is particularly so for those of us living in Australia, where we enjoy no comprehensive constitutional human rights protections which would otherwise allow for the courts to balance the competing individual freedom and public health interests. But the question remains the same for people everywhere: Does COVID-19 overreach remain a threat to our human rights? The answer is clear: it does. We must remain vigilant. ♦

P. T. Babie is ALS Professor of Property Law, Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide, Australia.

Recommended Citation

Babie, P. T. “The Global Pandemic and Government ‘COVID-19 Overreach.’” Canopy Forum, April 1, 2021. https://canopyforum.org/2021/04/01/the-global-pandemic-and-government-covid-19-overreach/