Resilience During a Pandemic:

What Citizens Teach Us About Faith, Policy and other Questions

Robin Fretwell Wilson

Ruby Mendenhall

Marie-Joe Noon

Karen Simms

Sara Buitron Viveros

Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash.

This article is part of our “Law and Religion Under Pressure: A One-Year Pandemic Retrospective” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

On March 21, 2020, Americans became shut-ins overnight. Around 245 million people in the U.S. found themselves under stay-at-home orders. In Illinois, where we teach and work, Governor J.B. Pritzker became one of the first few governors to enforce a state-wide stay-at-home order. Following recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Pritzker and governors nationwide instituted precautionary measures — mask mandates in public places, appropriate hand hygiene, and social distancing. Our individual worlds shrank to a pinpoint.

People lost their contact with coworkers, employers, neighbors, and sometimes even their own family. It was worse for those who came into the pandemic with the least. People lost jobs en masse. Women and people of color were dislocated more than others. And they were disproportionately at risk as essential workers.

Even before COVID-19, there were concerns about the adverse impact of loneliness on us. Loneliness is linked with increased feelings of anxiety and depression. The World Health Organization, CDC and national mental health organizations have all expressed significant concern about the impact that physical distancing, sheltering in place, and other COVID restrictions have on our mental health.

Loneliness also impacts us physically. Heart disease and strokes occur more often in socially isolated individuals. Loneliness has been associated with a 40 percent increase in the risk of dementia. While we do not fully understand why, the CDC believes loneliness and isolation are a serious public health issue. For many, this period of COVID restrictions with its attendant social and societal challenges has been absolutely overwhelming:

Most human beings simply cannot tolerate being disengaged from others for any length of time. People who cannot connect through work, friendships, or family usually find other ways of bonding, as through illnesses, lawsuits, or family feuds.

COVID-19 sparked a slowly unfolding trauma — meaning a series of adverse events that is overwhelming and shaping and defining. Common go-to resources have frequently been unavailable. Faith communities closed their doors. Food pantries were overrun. Children were suddenly unseen by teachers as schools shifted to remote learning. Not only was law and religion under pressure, but every aspect of our lives was besieged. Even journalists could not cast light on what was happening during the early part of the pandemic because of fears of contagion.

Insights from People

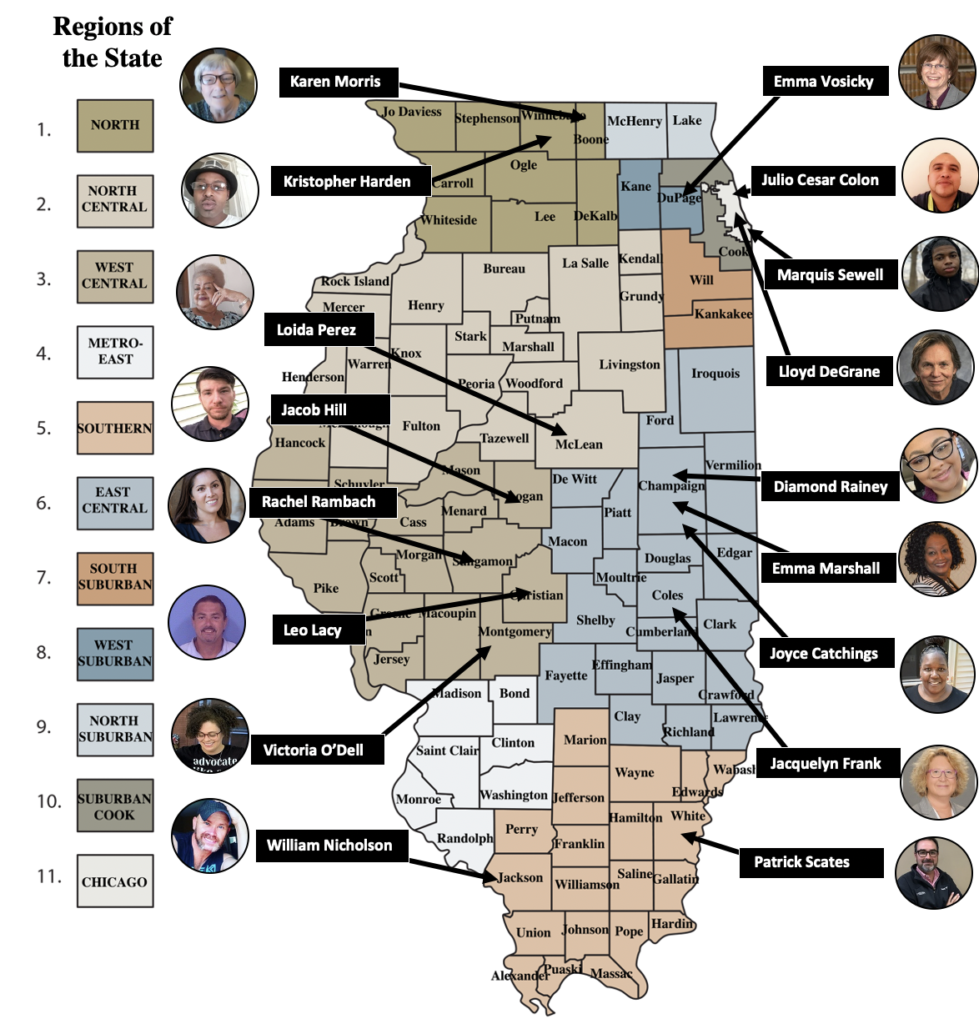

In an effort to better understand how Illinois residents have managed socially, emotionally, and economically during the COVID-19 pandemic, we asked 16 Illinois residents to journal once a week for six months. We drew from those most affected by the pandemic — older people and persons who are presently incarcerated or work as essential workers. Non-essential workers, persons in rural communities, small business owners and self-employed persons, students (over 18 years of age), members of the homeless community, members of the substance-use community, parents and caregivers, and members of the Black, Latinx, and LGBT communities all shared experiences. This broad net gave us statewide representation.

By journaling every week, our Citizen Scientists chronicled an unprecedented, historical event, made tangible by their re-telling in their own voices. In these pages are lessons about community, faith, resilience, halting progress, overcoming — and even the efficacy of public policies being put in place in real-time by a government struggling to mitigate impacts on people.

The Importance of Faith

Some felt cut off from communities of like-minded believers, and even God. Kristopher Harden, one of our Citizen Scientists, put it this way: “I was sad because people could not enter the church, worship God together, or do church activities that made people happy. . . .” The hole that this left for Kris cannot be overstated: “When the virus 1st hit, and the world changed it was emotional for [him]. [He] sat on the grass at [his] church eating lunch, with tears.”

As houses of worship shuttered or moved online, some who journaled for us missed connecting with their pastors, listening to sermons, and feeling close to God. For Joyce Catchings, “[i]t’s just not the same feeling for me!!!” She elaborates:

As I sit and watch my Pastor speak/preach on my tablet, it is just like sitting and watching a show on TV. He can’t hear me agreeing with him or saying Bless you Pastor when he says something I think differently about. I really wish there was a cure for COVID-19 or it dies off real quickly. Going to church being around like minded people as myself helps me deal with all the everyday struggles.

Pew Research Center reported in April 2020 that 24% of U.S. adults say their faith has become stronger because of COVID-19. For 2%, their faith has become weaker. Emma Marshall is emblematic of that larger group of Americans:

[A]s we enter our 7th month of no in-person church services, my faith has not waived. In some cases, it has been renewed and restored. Even though I personally struggle with technology, I am so grateful today that it is available to us. We are blessed to have virtual Bible studies and virtual Sunday morning services.

That so many rely on faith during hardship is perhaps not surprising. Spirituality — the belief in something greater than oneself — gives hope and helps fashion meaning from life’s experiences. It can be an essential part of helping people deal with and adjust to the negative effects of trauma and adversity. Even as churches closed to members, they also pulled into themselves. Jimmy puts it this way:

Lots of the church people walk by me now, trying to avoid the homeless. But now, with the Covid around it’s even worse. People act like I carry the disease.

As the United States Supreme Court grapples with challenge after challenge to the restrictions of people of faith gathering — even as governments allow commercial activities like shopping at Nordstrom — the restorative power of faith is not far from view. A majority of the Court reminded us that missing a Sabbath or even an additional day of prayer imposes an “irreparable harm.” The government “is not free to disregard the First Amendment in times of crisis.”

Masks and School Closures

No one doubts that public health measures were costly. Many of our Citizen Scientists stressed how hard it is to grasp “the new normal (shake my head)!” Even as masks became political, mask policy was anything but political — it was a reality for small business owners. Joyce Catchings, a daycare business owner, shared her struggles with “mak[ing] sure everyone has a mask on before [her daycare children and she] leave daycare.” It became her “duty to make sure they have [their masks]! Life altered for us all with having to wear a mask everyday . . . It’s a good thing for us all to stay healthy and safe!”

For the homeless, the need for masks threw up barriers. Kim shares:

On the streets, the working people, the civilized people that walk by us won’t be wearing a mask and then they see us and hurry up and put one on and walk around us. Like we have the disease. But the civilized people are the ones that meet with their friends and eat together and work together. Truthfully the civilized people are the ones who might give it to us and make us sick.

School closures were not academic matters, either. “In fulfilling the role of ‘mom’ 24/7 for all these months, [Rachel Rambach’s] roles of music therapist, business owner, writer, and singer/songwriter have all been pushed to the backburner.” Tori O’Dell, a reporter, photographer, and mother of two boys, one of whom is autistic, explains: “The biggest issue, for us, has been the temporary closures of the local therapy department, and G’s lack of access to services with both the school and the therapy department shut down.” Parents experienced enormous frustration when therapy services, whether through the state or the educational system, were made only periodically available, or not available at all, at a time when their children needed those services the most, as a way to cope with the pandemic.

Little wonder that CDC found that between August 2020 and February 2021, more than 1 in 3 adults reported recent symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder, while the fraction reporting unmet mental health needs increased to more than 1 in 10 (11.7%).

Not all of the unexpected challenges hastened by COVID-19 were bad. The new “normal” motivated some people to take more control over their lives. Lloyd Degrane, a freelance photographer who has been documenting COVID-19 experiences on Chicago’s homeless community, shares Greg’s perspective on how “[c]ovid [has] really changed the world.” Greg, who has been homeless with his girlfriend for over 10 years, believes that “[t]he uncertainty of [this whole pandemic] is making [him and his girlfriend] consider getting clean and trying to integrate [themselves] back into society.”

Our Citizen Scientists also report touching acts of kindness notwithstanding the risk of close proximity. Blue, shown here, chronicles his journey back from Austin to Dallas and, eventually, to Chicago, after being released from jail. Blue waits “for hours and hours” on the highway, right outside of Austin, hoping to get a car ride home. He ends up getting in the back of a pick-up truck heading to Dallas. In Dallas, he shares his story with a retired police officer who — seeing how truthful Blue was — offers to drive him all the way up to Chicago. Blue shares:

As we’re riding to Chicago I’m thinking about all the stuff I saw on TV, about people hating Cops but I’m talking to Jim and I’m thinking, Cops are just people too and now, after that long ride, I have a different feeling about Cops. They’re still human beings, some are messed up people but there’s the good people too. I accept that now. The Cops, they’re just like all the rest of us.

Policy from People

Just as people were cut off from each other, lawmakers and policymakers were cut off from constituents — an important source of information about policy. They simply couldn’t see the impact of their policies. In this respect, our Citizen Scientists filled an extremely important role. Consider Stacey’s story, shared by Lloyd Degrane:

It was great when the city [of Chicago] first brought down the portable hand washing machine but they haven’t changed the water very often so now the water smells rotten. I have to go out to an alley down the street and use a water spigot to wash my hair. It makes me think how unsafe it is to be washing my hands with recycled water. I’m pretty sure water alone does not kill COVID-19.

Stacey’s story is one example of how an effort to help the homeless community can boomerang, if appropriate steps are not taken.

Resilience

Our Citizen Scientists reported remarkable resilience. Our journalists not only illuminated policy, they found community with each other. Journaling has long been lauded for its curative effects and for being a judgement-free, no-rules process that can have physical health and mental health benefits. According to the Center for Journal Therapy, journaling is a healthy therapeutic tool for healing, growth, and change. Having an empathic witness is essential to healing from trauma. Journaling, especially journaling as a Citizen Scientist, can provide a powerful vehicle for healing through empathy and connectedness. By bearing witness to each other’s challenges and triumphs, our Citizen Scientists built stronger, connected, and healing relationships.

Arguably the most important contribution of the Citizen Scientists Journaling Project is to surface the experiences of people that might otherwise go unseen: a farmer in the downstate, a recovery specialist at a substance-use clinic, a prisoner at a state facility, a young man going to college.

Leo Lacy, our Citizen Scientist journaling with us from Taylorville Correctional Facility, talks about how “[s]tress on a regular human is hard enough. Stress on a man who is locked in a cage, and cant [sic] see his loved ones. Cant exercise [sic] his body. Cant [sic] release the built up tension from life and his situations. Is truly a recipe for disaster! . . . [Y]ou don’t [sic] have to be in prison to be a prisoner to something [sic]. Life is hard there [sic] is sickness of all kinds. And we need to stay strong.”

Conclusion

A year in, what’s certain is that this has been a challenging time for all of us. But we have learned a lot. When we recognize ourselves in another person’s challenges, it is much more likely that we work together to improve the status quo, especially for those for whom a lift from others can be so transformative. Suitable policies that identify and anticipate the immediate needs of the community begin with understanding. It is critical that we take selfishness out of the prospect of a better world. ♦

Robin Fretwell Wilson is the Director of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs for the University of Illinois System as well as the Mildred Van Voorhis Jones Chair in Law at the University of Illinois College of Law and the founder and co-director of the College of Law’s Family Law and Policy Program.

Ruby Mendenhall is an Associate Professor in African American Studies, Sociology, and Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Illinois. She is also the Assistant Dean at the Carle Illinois College of Medicine. She is also an affiliate of the Institute for Genomic Biology and the Institute for Computing in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences.

Karen Crawford Simms is a consultant, trainer, facilitator, and coach on mental health. She’s the founder Trauma & Resilience Initiative, Inc. a not for profit which is a part of the Champaign County Community Coalition.

Marie-Joe Noon is an Academic Researcher at the University of Illinois College of Law as well as a former Lebanese Fulbright Scholar at the University of Illinois and an Epstein International Health Law Ambassador for the Epstein Health Law and Policy Program. She received her Master of Laws (LL.M.) in International and Comparative Law from the University of Illinois’ College of Law (Class of 2020).

Sara Buitron Viveros is a labor and employment lawyer from Colombia. A graduate of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in 2015, she received her Master of Laws (LL.M.) from the University of Illinois College of Law in Legal Practice Skills (Class of 2020).

Recommended Citation

Wilson, Robin Fretwell et al. “Resilience During a Pandemic: What Citizens Teach Us About Faith, Policy and other Questions.” Canopy Forum, April 29, 2021. https://canopyforum.org/2021/04/29/resilience-during-a-pandemic-what-citizens-teach-us-about-faith-policy-and-other-questions/