Defiant Congregations in a Pandemic: Public Safety Precedes Religious Rights

Robin Fretwell Wilson, Brian A. Smith, & Tanner J. Bean

Photo by marybettiniblank on Pixabay (CC)

This article is part of our “Reflecting on COVID-19” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

Families across America are running for cover from COVID-19. And for good reason: as of today, the United States has over 15,000 confirmed cases. More than 200 Americans are dead. One of us, who leads a task force on COVID-19, has been told that absent responsible prevention, a coming tsunami of patients will overwhelm our healthcare system.

What does this mean for faith communities?

Some, but not all, churches are taking steps to protect their flock. In Dallas, a Christian pastor gathered congregants, splitting them into separate rooms to comply with the letter, but not the spirit, of Dallas’ limit on the size of community gatherings. Ducking the law put this pastor’s parishioners at grave risk.

We cling to faith, especially in times of crisis. Faith shores us up personally and as a collective. But gathering in the midst of a pandemic is an act of defiance that places at risk the very community that faith should lift up, that faith should shelter.

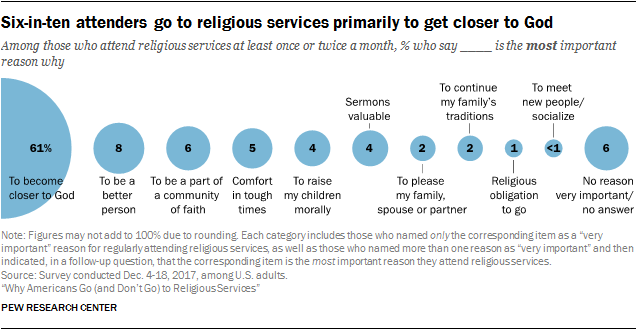

The impulse to gather as a people of faith, in ordinary and extraordinary times, is not uniquely a Christian phenomenon. Within the Jewish world, congregational worship may occur three times daily. Muslims have five daily prayers, sometimes together, sometimes alone. Gathering is important to many faith communities, with many individuals ranking religious services as essential to their religious identity.

Over the past two weeks, national, state, and local governments have imposed increasingly strict measures to “flatten the COVID-19 curve”—that is, to slow the spread of the virus so that our healthcare system is not overrun.

Americans have stepped up to mitigate our collective risk: we are all reacting to states of emergency, strict quarantine measures, the shuttering of borders, and the imposition of shelter-in-place orders. Schools have closed, universities have moved online in record time, businesses have virtualized operations, and public gatherings have ground to a halt. Even courts have pressed pause to limit the needless exposure of their employees and private litigants to the coronavirus.

To be sure, freezing Americans in place limits individual freedoms. The ability to gather as people of faith is our first freedom. But as with other freedoms now cabined in the name of public safety, religious freedom must take a backseat, at least for now.

The ability to gather as people of faith is our first freedom. But as with other freedoms now cabined in the name of public safety, religious freedom must take a backseat, at least for now.

During outbreaks or other public health emergencies, states have broad powers. They may place restrictions on movement, quarantine persons, mandate vaccinations against infectious agents, and limit public gatherings to prevent the spread of disease.

Nonetheless, some contend that despite the coronavirus’s unprecedented threat to the American public, there “must be a presumption in favor of full religious freedom for all religious communities in every country, especially in democratic countries.”

The federal government may burden religious practice when it enacts a neutral and generally applicable regulation, order, or law. The U.S. Supreme Court made this clear when it upheld, in Employment Division v. Smith, the denial of unemployment benefits for a Native American who ingested peyote as a part of his religious sacrament. The loss of benefits burdened him uniquely, but to push aside the law for the religious belief would make religious believers a law unto themselves, Justice Scalia observed.

After Smith, Congress imposed on the federal government the duty to show more when burdening religion with federal laws. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (“RFRA”) allows a person whose religion is burdened to ask a court to test whether that burden is necessary. The government must show a compelling interest for its action that the government cannot satisfy with less restrictive means.

In this pandemic, the laws regulating Americans most directly are state law, not federal. However, RFRA’s demanding test does not apply to state action, like the actions taken in California to lock down the Bay Area and the impending shelter-in-place order in New York.

Like Congress, many states have also demanded more proof from the state before burdening religious belief unnecessarily. Thirty-one states have state constitutional protections or state RFRAs policing religious burdens that flow from laws that are neutral and generally applicable. But this just means that judges must interrogate the need for restricting the movement of Americans during a pandemic. Given the extraordinary risk of transmission of the coronavirus, together with COVID-19’s lethality, finding a compelling interest in limiting gatherings to ten people or less or to making citizens shelter in place seems fairly straightforward.

Complicating this analysis are the many carve-outs or exceptions to some state orders. Obviously, health and safety orders should carve out persons who provide critical infrastructure, such as first responders like the police and firefighters. This is a no brainer: first responders are exempt precisely so they can serve all of us.

But some orders leave aside far more people. Blaine County, Idaho’s order, for example, leaves laundromats and dry cleaners unregulated—clean clothes are nice, but not needed to save lives. Appraisers and title companies are exempt—surely real estate closings can wait. Fine dining is not a matter of life and death.

As exemptions pile up, churches have a legitimate beef. When governments fail to apply burdens across the board, the argument that the government must restrict public gathering for worship in the name of the public’s health becomes less compelling. But the answer should be not to equalize up, giving everyone, including churches, exemptions. More carve-outs will gut the state’s public health safeguards. Instead, we need to equalize down. In a pandemic, we need fewer exemptions, not more.

…We need to equalize down. In a pandemic, we need fewer exemptions, not more.

Pushing back against the state in the name of faith is unnecessary, too. Consider the innovative ways faith communities are gathering virtually to provide solace and comfort. St. Martin in the Fields Episcopal Church in Aurora, Colorado is conducting “drive-by Sunday mass,” while other Colorado churches are linking people together through technology to fight social isolation. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has fully shifted from its public gatherings to a “home-centered church” approach with self-guided gospel study and in-home administration of sacraments. Scores of other congregations are broadcasting their services through livestream technologies and social media. The National Council of Churches has given permission for any church to use the Revised Standard Version and New Revised Standard Version bibles during these livestreams.

Others consciously place their members’ safety first. The Archdiocese of New York cancelled all Masses in the state, staying open only for private prayer. This act is deeply responsible and loving: New York is home to the largest cluster of COVID-19 cases in the United States. Already, in the Orthodox synagogue Young Israel of New Rochelle, both the rabbi and at least one congregant have acquired COVID-19. Numerous synagogues have closed in light of “sha’at ha’d’hak, an emergency.”

Now is not the time to stand on our rights. It is not the time to pursue contentious religious freedom claims in the courthouse. Instead, it is a time to lead by example, as so many congregations and people of faith have done and to put others first.

Robin Fretwell Wilson is the Director of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois System; the Lead of the IGPA Task Force on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic; and Roger and Stephany Joslin Professor of Law at the University of Illinois College of Law.

Brian A. Smith, MPH, is a law student at the University of Illinois College of Law (J.D. expected 2021).

Tanner J. Bean is an Employment Law, Religious Freedom, and COVID-19 Response Attorney at Fabian VanCott.

The views of the authors are expressed in their personal capacities.

Recommended Citation

Wilson, Robin Fretwell, Brian A. Smith, and Tanner J. Bean. “Defiant Congregations in a Pandemic: Public Safety Precedes Religious Rights.” Canopy Forum, March 21, 2020. https://canopyforum.org/2020/03/21/defiant-congregations-in-a-pandemic-public-safety-precedes-religious-rights/