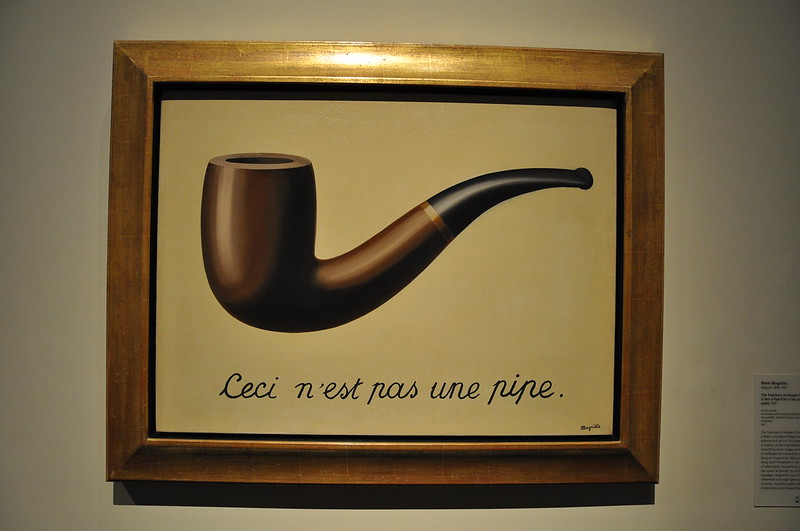

Ceci n’est pas une pipe:

The Crucifix in Italian Schools in the Light of Recent Jurisprudence

Francesco Alicino

With a 65-page decision, the Joint Section of the Supreme Court (Sezioni Unite della Corte di Cassazione), the highest Italian Court, has ruled on the display of the crucifix in public school classrooms. Issued on September 9, 2021, decision no. 24414/2021 synthesizes an extensive number of precedents, including those of the Italian Constitutional Court and other national-supranational judicial authorities such as the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights and the German, Canadian and Swiss high Courts. These precedents gave the Italian Supreme Court the opportunity to provide a unified mediation among the different (theistic, non-theistic, and atheistic) actors that had been fiercely debating the issue for at least thirty years.

The crucifix case involves Mr. Franco Coppoli, a full-time Italian literature teacher, who in 2008 took the religious symbol down from the wall of a classroom and rehung it at the end of his lessons. The teacher said that the presence of the crucifix behind him violated both his freedom of conscience and the principle of religious neutrality in public schools. Afterwards, the majority of the school’s student assembly adopted a resolution in favor of the compulsory display of the crucifix, so the school’s director (dirigente scolastico) issued an executive order mandating that Mr. Coppoli respected the presence of the religious symbol in the classroom. The teacher did not comply with the order. Thus, the school authority suspended Mr. Coppoli from teaching for 30 days without pay. In May 2015 the case went before the Joint Section of the Supreme Court where the teacher also complained that he was discriminated against for his nonreligious convictions.

It is important to note that laws regarding the compulsory display of the symbol of the Catholic Church date back to Articles 118 and 119 of the 1920s royal decrees (nos. 965/1924 and 1297/1928), under which the Italian public schools “shall have the national flag” and each classroom’s wall need “a portrait of the King and a crucifix”. Although enacted in the context of both the 1848 Statuto Albertino (the Constitution of the Italian Kingdom, whose first Article granted Catholicism the status of State religion) and under the confessional attitude of the Fascist regime (as clearly demonstrated by the 1929 Lateran Pacts, the 1159/1929 law on “admitted religions” as well as Articles 402-406 and 724 of the 1930 Criminal Code), the royal decrees remained valid even after the 1948 Republic Constitution was approved. Moreover, these decrees are still in force today, as the Italian Parliament has never considered it necessary to intervene in the matter.

The rule framework concerning the display of the crucifix in State-school classrooms is extremely uncertain and jurisprudential interpretations frequently contradict each other.

This explains why the rule framework concerning the display of the crucifix in State-school classrooms is extremely uncertain and jurisprudential interpretations frequently contradict each other; this is even more evident when referring to the supreme principle of secularism (principio supremo di laicità), as the Italian Constitutional Court has called it since the 203/1989 historical decision. This also explains the background of the September 9 sentence, whose reasonings and arguments can be fully understood in light of the previous debate and judicial precedents, starting with the one the Fourth Criminal Division of the same Supreme Court issued on the first of March, 2000, no. 4273/2000.

The crucifix and Italy’s principle of secularism

The 4273/2000 case-law concerned a scrutineer who had refused to perform his public duties in the Italian polling stations during the election. This was because the vast majority of these stations were, and are, located in State-school classrooms where there were, and are, symbols belonging to a single religious faith: the Roman Catholic Church. The scrutineer viewed the presence of the crucifix as violating his right to freedom of religion and conscience. The Court’s Criminal Division ruled that the impartiality of scrutineers’ public function is closely related to the neutrality of the places designated for the decision-making process in electoral competitions. This reasoning derived from the content of the State secular law, under which election sites could not tolerate the compulsory presence of images, signs and figures exclusively reflecting the views of one confessional group, even the majority religion. The Court’s conclusion, however, did not mean that the display of crucifixes in State-school classrooms is always illegitimate and contrary to the principle of secularism, depending on the conditions, scenarios, rights and freedoms reported in individual trials.

It is important to note that while secularism is not expressly mentioned in the Italian Constitution this has not prevented the Constitutional Court (ICC) from implying otherwise. On the basis of a series of constitutional provisions (namely Articles 2, 3, 7, 8, 19, 20 Const.), ICC has demonstrated that secularism is one of the supreme principles (principi supremi) of the Italian legal order. While recognizing that all persons are equal before the law and entitled to freely profess religious belief in any form, individually or with others, the supreme principle of secularism does not imply indifference towards religions. Conversely, it confers a special legal status to religious denominations while still maintaining the equidistant and impartial relationship between the State and individual religions.

This suggests that Italy’s supreme principle of secularism is legally delineated through the combination of favor libertatis, as stated in Articles 2, 3 and 19 of the Constitution, and favor religionis, as illustrated in Articles 7, 8 and 20 of the same Charter. While favor libertatis puts emphasis on individuals’ rights and freedoms to choose and practice their religious and nonreligious beliefs, favor religionis gives special attention to religious denominations and institutions, including the majority one. This combination does not always result in harmonious coexistence. The complex and contradictory administrative jurisprudences concerning the display of the crucifix in public schools are the most tangible examples of that.

Secularizing the crucifix

In 2005, for instance, TAR Veneto, Veneto’s Regional Administrative Tribunal, gave a peculiar explanation of both the principle of secularism and the crucifix, which maintained that the secular nature of modern states is strictly related to the founding values of Christianity. In this sense, they said, the crucifix should be considered not only as a religious symbol, but also as the symbol of human dignity, tolerance, and freedom. As such, the compulsory display of the crucifix in State-school classrooms does not clash with the State law for the reason that, as TAR Veneto further explained, this symbol represents not only the values of the Catholic Church, but also the basic values of the Constitution, including those referring to the supreme principle of secularism.

In support of these arguments, one year later the Supreme Administrative Court (Consiglio di Stato) emphasized the importance of the location where the crucifix is displayed. In a place of worship, they said, this symbol has a religious character — in other spaces it can have other meanings. The Court inferred that the significance of the crucifix is given not only by the text (symbol) but also by the context (space) where it is displayed. Moreover, the Supreme Administrative Court ruled that in State-school classrooms the crucifix has a democratic meaning, and as such it is a non-discriminatory symbol, regardless of the pupils’ religion.

In a kind of Orwellian doublethink, Veneto’s Regional Tribunal and the Supreme Administrative Court seemed to maintain two opposing ideas: the crucifix is both viewed as a symbol of the Catholic Church and the expression of a secular state. For the same reason, these decisions also recall René Magritte’s famous picture La trahison des images (The treachery of images) showing a pipe with the words ceci n’est pas une pipe (“this is not a pipe”).

In any case, the two different jurisprudential avenues – the one related to the 4273/2000 Supreme Court’s decision and the one marked out by the 2005-2006 administrative sentences – were furthermore complicated by other case-laws such as TAR Lombardia, Lombardy’s Regional Administrative Tribunal, issued on the 22nd of May, 2006. Here the Tribunal rejected the appeal of an elementary school teacher who removed the crucifix during her lesson against the will of the school authority. In doing so, TAR Lombardia introduced a new, nuanced interpretation, under which the order to reinstall the crucifix should come out of a consultation with the school’s interclass council. This meant that the solution must be found on a case-by-case basis, through an agreement among the users (teachers, students, school authorities, parents) of spaces concerned.

This approach has both advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that the decision is left in the hands of the people who are directly involved. The disadvantage is that, apart from rare unanimous agreement, a decision based on majority opinion would always lead to the discontent of those in the minority, if not the outright infringement of their right to freedom of and from religion.

These problems are also reflected in the issue of the all/no symbols dichotomy that, as Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura (the self-governing body of Italy’s ordinary judges) has stressed, generates other negative effects. Admitting the display of all religious symbols would discomfort non-believers and raise the question of which symbols to permit in public spaces, while the white-wall solution would be more compatible with a conception of secularism with the French laïcité de combat than the Italian principle of laicità and its positive attitude towards the public role of religious denominations, notably Catholicism, the major religion in Italy.

On the other hand, these problems also reflect the incapability of public authorities, including the Courts, to take the bull by the horns and legally define the real meaning of the compulsory display of crucifixes in state-school classrooms and the content of the supreme principle of secularism. Indeed, both of these questions still remain largely unresolved.

The European supranational jurisprudence

Perhaps it is not by chance that those difficulties are being replicated, albeit from a different perspective, in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which fulfills a similar role as the Italian ordinary courts, albeit at the supranational level.

ECtHR tends to follow the stare decisis rule, abiding by its own precedents. As such, this Court normally takes into account the merits of the case-laws and the relative facts. This means that many times the concrete facts of the case end up playing a very important role in the ECtHR’s final decision. In particular, this happens when the facts of the case are directly or indirectly connected with the prohibition of discrimination, as enshrined in Article 14 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR). This is especially the case for the right to freedom of religion (Article 9 ECHR) in both the individual and collective sense of the term.

It is also important to stress that the machinery of protection established by the European Convention of Human Rights is subsidiary to the national systems. The Convention leaves to each contracting state the task of securing the rights and liberties it enshrines. By reason of their direct and continuous contact with the populace of their countries, state authorities are obviously in a better position than ECtHR to opine on the exact content of those rights and freedoms as well as on the “necessity” of “restrictions” on them. In other words, the principle of subsidiarity refers to the subsidiary role of the ECHR’s machinery and entails a procedural relationship between the national authorities on the one hand and the Convention institutions on the other. This means that member states have an obligation to secure the ECHR’s rights within their domestic sphere before they are brought before the Court of Strasbourg. The principle of subsidiarity is often connected with the balancing principle, under which judges seek to resolve conflicts between fundamental rights, and between these rights and competing public interests, by balancing one against another.

This is in turn frequently translated into a proportionality test, which must be conducted in order to check whether an interference with a fundamental right provided by the European Convention is proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued by the legal restriction imposed at the national level on rights and freedoms. It is important not to forget however that the outcomes of this test depend on the European consensus standard, which is a generic label used to describe ECtHR’s inquiry into the existence or non-existence of a common ground, mostly in the law and practice of the Member States. And it is not by chance, but rather by the principle of subsidiarity, that this standard has played a key role in the wider or narrower character of the application of the more notorious margin of appreciation.

All of this often results in a complex and ambiguous jurisprudence, in which ECtHR has sometimes moved in one direction and sometimes in another. This is even more evident when referring to the decisions related to the presence of religious symbols in public spheres. The two conflicting Lautsi v. Italy decisions are illustrative examples of this ambiguity.

It should be noted that at the national level Lautsi 1 (2009) and Lautsi 2 (2011) began with the above-mentioned decisions of TAR Veneto and the Supreme Administrative Court. In particular, the case involved Ms. Lautsi and her two children aged eleven and thirteen. From 2001-2002 the two boys attended the state school Vittorino da Feltre based in Abano Terme (Padua). Ms. Lautsi considered the school’s practice of displaying the crucifix in each of the classrooms contrary to the State’s secular law. She raised the question at a meeting held by the school, pointing out that Corte di Cassazione, in above-mentioned decision no. 4273/2000, had ruled that the presence of a crucifix in the polling stations prepared for political elections was contrary to the supreme principle of secularism. In May 2002 the school’s authority decided to leave the crucifixes in the classrooms. In July 2002 Ms. Lautsi challenged the decision before TAR Veneto that, in 2003, referred the case to the Constitutional Court. In ordinance no. 389/2004 the Constitutional Court ruled that it did not have jurisdiction because the issues raised by Ms. Lautsi were dealt with by regolamenti (regulations), which did not have statutory force of law. As noted before, with the judgment no. 1110/2005 TAR Veneto dismissed the applicant’s complaint, and so did the Supreme Administrative Court a year later.

On July 2006, after having exhausted all state juridical solutions, Ms. Lautsi brought the dispute before ECtHR. On November 3, 2009, the Second Section of the Court stated that while the symbol of the crucifix has a number of meanings,the religious one is most predominant. Its presence in State-school classrooms may be encouraging for some religious pupils, but it may be emotionally disturbing for pupils of other religions or those who profess no religion. In the context of education, the Second Section further clarified, the compulsory display of a symbol of a particular faith is perceived as an integral part of the school environment and may therefore be considered a “powerful external symbol,” as it was in the case of Dahlab v. Switzerland.

Thus, in the Lautsi 1 decision, the court ruled that the presence of crucifixes in schools restricted freedom of religion, which is incompatible with the State’s duty to respect neutrality in the exercise of public authority, particularly in the field of education. Consequently, the Second Section concluded that there had been a violation of both Article 2 of ECHR’s Protocol no. 1 (under which “the State shall respect the right of parents to ensure such education and teaching in conformity with their own religious and philosophical convictions”) and Article 9 ECHR (concerning freedom of thought, conscience and religion).

ECtHR Second Section’s ruling caused vivid opposite reactions in public opinion and in academia, which were sharply divided on the issue: while the Court’s decision was welcomed by atheists and many non-religious people, an extensive number of intellectuals and political actors, including on the left of the electoral spectrum, defended the crucifix as an expression of State identity. Moreover, the President of the Council of Ministers Silvio Berlusconi immediately dismissed the decision as “unacceptable for Italians”; he also added that this is one of those sentences that “make us doubt Europe’s good sense.” Even the President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano cautiously but firmly said that the “sensitive issue regarding the use of religious symbols in public spheres” needs to be dealt with at the national level. These considerations may help to explain the fact that, on January 28, 2010, the Italian Government asked for the case to be referred to the ECtHR Grand Chamber, which granted the request on the first of March, 2010. It is important to note that this proceeding brought together “strange bedfellows,” such as the Vatican, the Russian Orthodox Church and American Conservative Evangelicals, all united by their advocacy of Christian symbols in the European public sphere.

It was in this curious atmosphere that the Grand Chamber issued the sentence of Lautsi 2.

The Grand Chamber ruled that the impact of a religious symbol on persons’ rights varies according to specific and concrete circumstances. As stated in Dahlab v. Switzerland, the Islamic veil worn by a teacher is a strong external symbol. This, however, was not the case for crucifixes hanging on State-school classrooms’ walls, which did not have the same impact. In light of the environments where, and the way in which it is displayed, the crucifix is an essentially passive symbol, the Chamber further clarified. On the other hand, Europe is marked by an extensive diversity, particularly in the sphere of cultural and historical development. That was of crucial importance in the Grand Chamber’s view, especially when referring to the principle of State neutrality.

All of this led the Chamber to affirm that the Member States enjoy a margin of appreciation in their efforts to reconcile exercise of the functions they assume in education with respect for the right of parents to ensure such education is in conformity with their own convictions. In this context, and under a diversified cultural-religious scenario, ECtHR Second Section had the duty to respect the State’s decisions in the matter, which implies the place that the State accords to religion, provided that those decisions do not take forms of indoctrination. It followed that, in deciding to keep crucifixes in the classrooms, the Italian public authorities acted within the limits of the margin of appreciation. Accordingly, the Grand Chamber concluded that there has been no violation of Article 2 of Protocol no. 1 taken in conjunction with Article 9 ECHR.

While emphasizing the doctrines of consensus and the specific domestic circumstances, the Grand Chamber minimized the ECtHR Second Section’s considerations based on general principles, starting with those referring to State neutrality. Thus, depending on the perspective and the point of view, the compulsory display of the crucifix in Italy’s public schools could be considered either discriminatory towards religious/non-religious minorities, and as such incompatible with the State’s duty to uphold confessional neutrality in education (Lautsi 1), or not necessarily associated with compulsory teaching about one religion, and as such not in contrast with the State’s principle of neutrality and religious freedom of minorities (Lautsi 2).

In the end, the country’s margin of appreciation prevailed, which did not eliminate the fact that within the boundaries of the Italian legal order diverging views still persisted, as the Constitutional Court had not given a ruling and the opinions of the Supreme Administrative Court and Corte di Cassazione diverged in that regard. That also explains the relevance of the September 9 decision of the Joint Section of the Supreme Court, a decision that, in many aspects, has nonetheless failed to meet the burden of perhaps unrealistic expectations.

The background of the September 9, 2021 Supreme Court’s decision

It should be noted that the 24414/2021 decision seems, at the moment, to please almost everyone; at the very least this sentence has not been the focus of such animated discussions as the 2004-2006 administrative jurisprudences and ECtHR’s Lautsi decisions. As noted before, the Supreme Court’s ruling was issued on September 9, 2021. Since then it has received little attention from both mainstream media and scholars.

It is also important to stress that the Italian Supreme Court was able to benefit from the previous debate and the huge number of national and supranational judicial precedents, thanks to which the legal issues at stake were clear enough. The Court, however, did not passively adhere to these precedents. In fact, while updating (and in some aspects renewing) the interpretation of the legal principles related to the compulsory display of the crucifix in public-school classrooms, the Supreme Court’s Joint Section took into serious account its main function, what Italian scholars like to define as nomofilachia.

The term nomofilachia derives from the Greek noun νόμος, meaning nomos (law), and the verb φυλάσσω, which refers to the ability of preserving something of value such as a right, tradition or idea. Established in Article 65 of the 12/1941 decree regulating the Italian judicial system, Corte di Cassazione’s primary purpose is funzione nonofilattica (the function of nomofilachia), that is, to govern statutory principles of interpretation and, as such, function as the guardianship of the state law’s uniform and workable consistency. Italy’s Supreme Court is hence called on to provide guidance on points of interpretation, which may be of assistance in adjudicating pending lower-court cases and ensuring that the Italian laws are interpreted in the same way throughout the State’s territory. Funzione nonofilattica is even more evident in the light of the 40/2006 legislative decree, which intends to give greater weight to the interpretation of the Supreme Court’s Joint Section.

In this context, it is also important to remember the Office called Massimario, which is based at, and placed at service of, the Supreme Court. Massimario’s job consists of studying the precedents of the different Sections of this Court, thus seeking to isolate the logic and reasonings of their decisions and distinguishing them from other arguments and obiter dicta. In other words, Massimario’s basic aim is to disseminate information inside and outside the Italian Supreme Court, which is necessary for the exercise of funzione nonofilattica.

It is not by accident that, in relation to the 24414/2021 sentence concerning the compulsory display of crucifixes in public schools, both the previous debate and Massimario’s information played a very important role.

The crucifix is a religious symbol

With the 24414/2021 decision the Italian Supreme Court first noted that the compulsory display of the crucifix is provided by the above-mentioned 1920s royal decrees. As such, and as the Constitutional Court had already underscored, these decrees did not have force of primary legislations: they are secondary sources of law, also known as regolamenti (regulations). The Supreme Court also stated that the crucifix is not a generic cultural symbol, but a specifically religious one. This led the Court to affirm that the compulsory nature of the display of crucifixes is in contrast with the supreme principle of secularism. This principle, on the other hand, does not imply indifference towards religions: while acknowledging the special status of confessions and protecting individuals’ manifestation of religion, Italy’s secularism implies pluralism and the impartiality – i.e. neutrality – of the State.

The Supreme Court thus inferred that the 1920s royal decrees could not be applied in order to justify disciplinary sanctions for Mr. Coppoli. This conclusion, however, does not automatically translate into the ban on the display of crucifixes in public schools.

The Supreme Court explained that, in principle, the presence of the crucifix is not a discriminative act against non-religious people and/or persons belonging to religions other than Catholicism.

The Supreme Court explained that, in principle, the presence of the crucifix is not a discriminative act against non-religious people and/or persons belonging to religions other than Catholicism. Adhering to the Lautsi 2, the Italian Court considered the crucifix a passive symbol. Its display in classrooms therefore does not necessarily indoctrinate students into a specific religious belief system: there is no evidence to support the claim that its display serves to influence students on this matter. In addition, the Supreme Court affirmed that, while the disciplinary sanction for Mr. Coppoli was not fully justified, the teacher did not face discrimination. Freedom to manifest one’s own nonreligious convictions does not require and is not achieved by means of an absolute ban on the display of the crucifix or an obligation to remove it from a shared public space. So why was the suspension of Mr. Coppoli illegitimate?

The disciplinary sanction against Mr. Coppoli was based on a majority vote, which had been taken during an assembly of the school students. More specifically, the school’s director adopted the sanction without taking into account the teacher’s dissenting opinion. Therefore, the director failed in his duty to help the students and the teacher find a compromise solution that was acceptable to, and respectful of, all parties involved. From here stems the core of the 24414/2021 decision.

While affirming that the compulsory display of the crucifix clashes with the principle of secularism and that the exhibition of this symbol is no longer obligatory but only optional, the Joint Section of the Supreme Court underscored the importance of an open-public debate involving all school bodies and aimed at reaching reasonable results. As such, these results must be capable of satisfying different needs. In particular, according to both the principle of proportionality and the nature of the balancing test, the debate should aim at accommodating the rights and freedoms of all persons involved.

Whether this is possible in practice remains to be seen, however.

The Court was aware of the practical problems in implementing a method-procedure such as this one. Therefore, the 24414/2021 ruling also provided indications on how the final decision of the school authority should be reached. The school’s director, the Court said, must assume the role of mediator during a comprehensive consultation process that must take into account the opinions of all parties involved, including minority students and dissenting teachers. Different solutions can be adopted. For example: the display of the crucifix on another wall that is not behind the teacher’s desk; the display of other religious or nonreligious symbols; the display of the crucifix with a phrase attached referring to the secularism’s history and heritage; and even the temporary removal of the crucifix during a lesson. Any of these solutions are possible, provided that they are decided at the end of a procedure that aims at reaching a reasonable balance between the conflicting rights and freedoms.

It should be noted that the content of the 24414/2021 decision is similar to that of Article 7(4) of the 1996 Bavarian law (Bayerisches Gesetz über das Erziehungs- und Unterrichtswesen, BayEUG), which was approved after Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court had issued an important ruling on the same matter (BVerfGE 93, 1 – Kruzifix); the contents of Article 7(4) also reflect those of the 18 December 2009 Italian draft law which, however, has never entered into force. Indeed, the 1996 Bavarian law states that if the parents raise reasonable objections against the display of the religious cross in elementary school classrooms, the school’s director shall attempt to reach an amicable agreement; if no agreement is possible, after informing the national education authority, the director has to find an optimal arrangement that respects freedom of belief of dissenters and brings about a fair balance between religious and ideological convictions of all parties involved. It is also important to note that on 2018, with the auspices of the State Premier Markus Söder of the Christian Social Union (CSU), Bavaria introduced the Kreuzpflicht (cross obligation) law, what has sparked an animated controversy about religion and secularism in Germany: under this law, Christian crosses shall have to hang in the entrance of “all public buildings,” something which is quite problematic in a number of ways, including legally.

Conclusion . . . for a case that is not fully closed yet

Italy’s principle of secularism is based on the conception of a “plural secularism” (laicità pluralista). As such, the Italian laicità is different from other models of secularism, like those referring to the French militant secularist model, bent on keeping religion completely out of the public sphere, or the communitarian model, in which high priority is given to collective self-government by each religious community within the State. While acknowledging the State’s impartiality and neutrality, Italy’s secularism combines favor libertatis (Articles 2, 3 and 19 Const.) with favor religionis (Articles 7, 8 and 20 Const.), which both recognize all persons, all religious groups and nonreligious beliefs as equal and equally free before the law and entitles them to freely profess, practice and propagate religions and nonreligious beliefs in any form, individually or with others. In other words, Italy’s secularism encompasses all manifestations of beliefs and disbeliefs, including atheism, rationalism, humanism, and agnosticism.

In the light of these considerations, the 24414/2021 ruling seems to be an attempt to better combine favor libertatis and favor religionis with the State neutrality, what are the main aspects of Italy’s supreme principle of secularism. But again, what exactly this attempt will produce in practice remains to be seen.

Under the September 9, 2021 ruling, every State school or even every classroom can adopt different solutions (naked wall, displaying crucifixes, displaying different religious and nonreligious symbols, etc.), depending on the result of a democratic debate, which translates in a random process: the display of religious symbols in general and the crucifix in particular would be decided on the basis of the participation and consensus of all parties concerned. On the other hand, however, this procedure becomes problematic when considering the fact that the issue involves constitutional rules and principles, including those related to Italy’s supreme principle of secularism.

In other words, the risk with the 2021 Supreme Court’s decision is that when referring to the display of the crucifix in State-school classrooms, secularism, far from being considered as a supreme principle, would be reduced to just a “method”; a method that, for the above-mentioned practical problems, does not always accommodate reasonably different views and ideas. If the white-wall solution could have generated at least a homogeneous protection of various rights and freedoms throughout the State territory, the Supreme Court’s decision does not reduce the impact of the long-standing issues concerning the display of the crucifix in public schools. In sum, while rightly emphasizing the essential characteristics of the principle of secularism and its reasonable attitude toward cultural-religious pluralism, the Supreme Court’s decision raises other concrete questions that are not easy to resolve.

These questions, however, do not detract from the fact that the 24414/2021 ruling marks an important legal milestone. The sentence makes it clear that, unlike the legal system prior to 1948, the compulsory display of the crucifix in public-school classrooms directly contrasts with the Constitution. This is because the crucifix does not belong to the State, meaning it is not an expression of the Italian Republic. It is an expression of both the faith of Christians and Catholicism, irrespective of places it is exhibited. Here the Supreme Court has been very careful not to perpetuate the treachery of religious symbols and their specific meanings.

Thus, from this very point of view, one could even argue that the Court looked at the crucifix as if to say ceci n’est pas une pipe. ♦

Francesco Alicino, Ph.D, is Full Professor in Public Law and Religion at the University of LUM (Casamassima, Bari, Italy), where he also teaches Constitutional Law, Law of the Third Sector, and Immigration Law. He is a member at the Italian Council for the relationship with Muslim communities based at the Italian Minister of the Interior. He is the Editor of the Italian first-class review Daimon (Il Mulino). He is professor with a temporary appointment at the School of Government based at LUISS Guido Carli (Rome). He is a member of ICLARS (International Consortium for Law and Religious Studies). He is senior fellow at the Institute of S. Pio V (Rome), where he has been coordinating several projects on freedom of religion-belief, religion-inspired terrorism, religion and sustainable goals, and the state-religions relations in the Mediterranean area. He is the national coordinator of EUREL (Sociological and Legal Data on Religions in Europe) based at CNRS University of Strasbourg. He is the author of several books and articles in English, Italian and French.

Recommended Citation

Alicino, Francesco. “Ceci n’est pas une pipe: The Crucifix in Italian Schools in the Light of Recent Jurisprudence.” Canopy Forum, November 30, 2021. https://canopyforum.org/2021/11/30/ceci-nest-pas-une-pipe-the-crucifix-in-italian-schools-in-the-light-of-recent-jurisprudence/