Locke, Toleration and Political Participation:

A New Manuscript

Craig Walmsley

Portrait of John Locke by Godfrey Kneller. (PD-US).

A manuscript by the philosopher John Locke recently discovered in North Carolina raises fundamental questions of political participation.

John Locke’s influence on the Founding Fathers in their formulation of the U.S. Constitution is well-known. It was Locke who argued, in the 1689 Two Treatises of Government, that government depends upon the consent of the governed. And it was Locke who asserted that same year, in his Letter concerning Toleration, that Church and State should be separate, and people should be free to worship God as they saw fit. Less well-known, but of equal importance to his worldview, are the exceptions he made to his arguments for religious freedom. The role Locke played in writing one of the first constitutions for the American colonies – The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina – is also little-known. It is perhaps fitting then, that an entirely unknown manuscript by Locke has recently been discovered in North Carolina which sheds new light on the origin and evolution of Locke’s views on toleration, and how these came to inform the U.S. system of government from the colonies to the present day. (The analysis presented below owes a significant debt to the co-author of our paper on this discovery, Felix Waldmann, J. H. Plumb College Lecturer and Fellow, Christ’s College Cambridge.)

Locke and Toleration

In the 16th Century, the Reformation unleashed waves of religious persecution across Europe, and in the 17th, religious disputes helped fuel the English Civil War (1642-1651). For Locke, born in 1632, religious tolerance was a pressing personal matter of life and death — his father had fought in the war, and the political convulsions it unleashed reverberated throughout Locke’s lifetime.

Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, but political reversals in 1667 meant he had to seek support amongst religious “nonconformists,” despite his role as head of the Church of England. The final months of 1667 and the first of 1668 witnessed an outpouring of works on the “comprehension” or “indulgence” of nonconformity: the issue of whether the Church of England would “comprehend” dissenters within its ranks or “indulge” their external worship. The key question was how far any such tolerance should extend — to any denomination of Protestant, to Catholics, to other religious faiths, to Atheists?

Locke, then factotum-cum-advisor to Anthony, Lord Ashley, a canny political operator of the time, drafted the manuscript “Reasons for tolerateing Papists equally with others” to help answer this question. Locke’s arguments in the “Reasons” evolved into his 1667 manuscript Essay concerning Toleration as an attempt to stake out a defensible position. Church and State were separate and — so long as religion didn’t foment sedition — people could worship God however they chose.

But once the immediate crisis passed, Locke seems to have set the Essay aside.

Locke and The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina

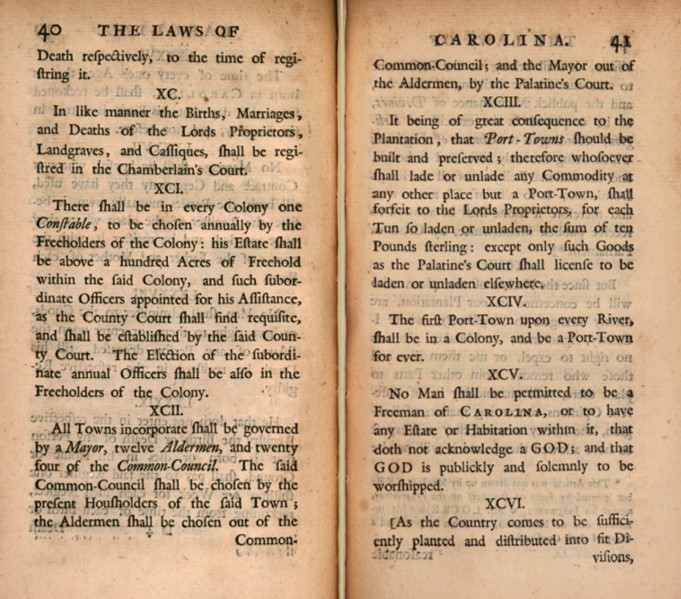

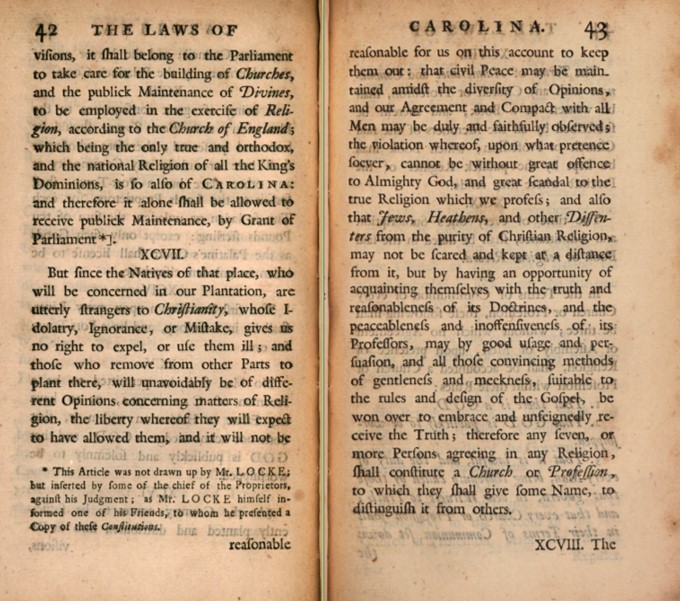

Not long after, in early 1669, Locke had the chance to translate some of this theory on toleration into practice. He helped draft The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina for Ashley and the other Lords Proprietors of the province. The Fundamental Constitutions was the first attempt to create a systematic political structure in the new colonies, and the society Locke helped formulate was notable for its religious tolerance.

The “Natives of that place,” Locke wrote, “will unavoidably be of different opinions, the liberty thereof they will expect to have allowed them.” “And also that Jews, Heathens, and other Dissenters from the purity of the Christian Religion, may not be scared and kept at a distance from it…any seven or more persons agreeing in any Religion shall constitute a Church.” This new state would be tolerant.

But some were still excluded from political participation. No-one shall be a “Freeman of Carolina” Locke wrote, “that doth not acknowledge a GOD.” Everyone had to profess their belief, undertake public worship, and bear witness to the truth by swearing upon this belief. People were free to worship how they saw fit — but religion would be an integral part of this new society and every citizen would be required to acknowledge a belief in God.

Samuel Parker’s Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie

Later that year, the conservative writer Samuel Parker published A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie (London, 1669).

A somewhat belated contribution to the “comprehension” debate of 1667-8, Parker argued that people were free to believe whatever they liked, but that the magistrate should control the “outward Practices” of religion to ensure uniformity and maintain civil peace. This cut to the heart of the arguments Locke had advanced in the Essay concerning Toleration, where matters of conscience — speculative or practical — were outside the magistrate’s competence.

Locke’s Manuscript “S Parker of Toleration”

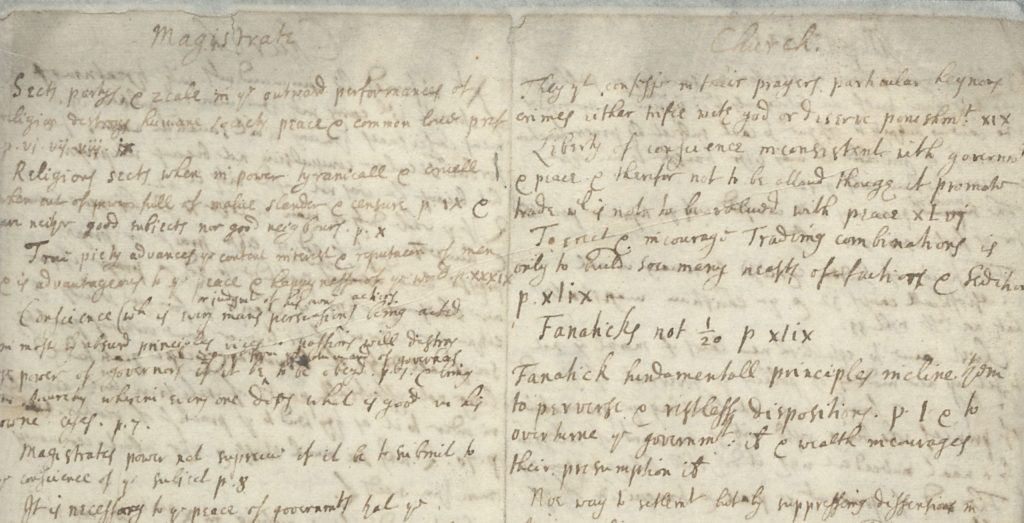

Locke sought to respond, and the new manuscript, titled “S Parker of Toleration” comprises 3,000 words of his notes and queries on Parker’s Discourse, separated into two columns titled to reflect the division between “Magistrate” and “Church.”

Locke thought Parker’s distinction was unworkable — you just can’t separate conscience from worship in the way Parker supposes. “He sets noe bounds to conscience how far it is or is not to be tolerated,” Locke writes, so how can we draw a clear line between inward belief and outward expressions? For example, Locke asks, “what becomes of those things I judg unlawfull?” — how can I acquiesce in outward actions that violate my beliefs about what God would want me to do? “Why soe much stress & stir about ceremony”? Locke asks. Are ceremonies really the most important part of religious belief? This newly recovered manuscript shows that Locke was far from impressed with Parker’s attempts to impose religious conformity.

The Foundations of Locke’s Political Society

But Locke did not reject everything that Parker said. As part of his argument for conformity, Parker asserted that religion played a foundational role in society:

There being for certain nothing so absolutely necessary to the reverence of Government, the peace of Societies, and common Interests of mankind, as a sense of Conscience and Religion: This is the strongest Bond of Laws, and only support of Government; without it the most absolute and unlimited Powers in the World must be for ever miserably weak and precarious, and lie always at the mercy of every Subjects passion and private Interest.

(Parker, Discourse, p. 141)

Locke read this — and paraphrased it in his notes — then read on. But the argument clearly stuck with him, because he went back to his paraphrase to add a new interlinear query, which did not criticise Parker’s argument, but instead built upon it:

Q whether this extends any farther then a beleife of god in general. but not of this particular worship

(John Locke, “S Parker of Toleration”, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, Southern Historical Collection, 03406 (Folder 323), fo. 2r)

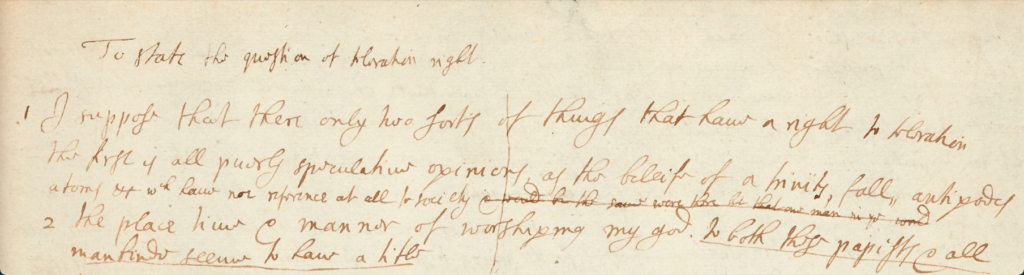

For Locke, belief in a deity would entail belief in punishment in the afterlife, guaranteeing honesty and morality in this life, and facilitating the establishment of mutual trust and political society. Locke here holds that belief in God “in general” is sufficient to ensure the moral conduct of a political subject and make someone fit for society, not just a particular form of worship. This extends the point made by Parker, and elevates the practical points of the Carolina Constitution to the principled position that “mere theism” must underpin peaceable civil co-existence.

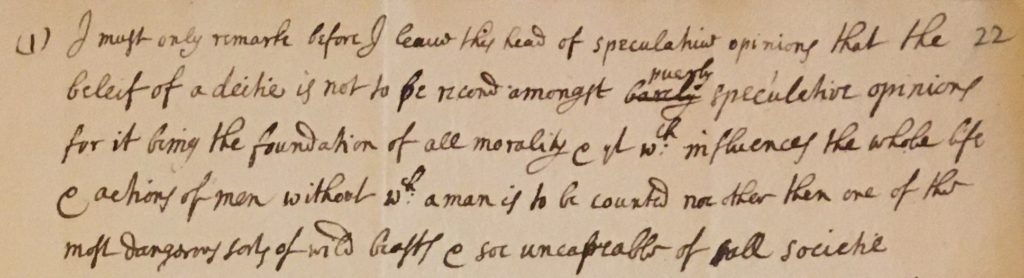

Locke’s Exclusion of Atheists

But such a reliance on religious belief as the foundation of the polity has a clear corollary — non-believers would have no fear of God’s punishment and would, in Locke’s view, be inherently unreliable. They must, as a consequence, be excluded from political society. So when Locke came to revise his Essay concerning Toleration a few months later, he made a significant new addition to his argument — atheists cannot be tolerated. Without the “beleif of a deitie … a man is to be counted noe other then one of the most dangerous sorts of wild beasts & soe uncapeable of all societie.”

This newly discovered manuscript thus shows that Locke set this strict limit to his toleration while reading Parker — a deeply reactionary figure (which is a bit like discovering that Marx first noted one of his key arguments while studying the same point in Burke). Locke would make similarly pointed assertions about atheists with the publication of his 1689 Letter concerning Toleration, the work that profoundly influenced the Founding Fathers’ views on the role of religion in society.

Locke’s Religious Test

The recovery of this manuscript thus raises important questions about the foundations of the American state. When Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence that “that all men are created equal … endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,” he was paraphrasing the Two Treatises of Government. When he later wrote that there should be “a wall of separation between church and State,” he was echoing Locke’s division between “Magistrate” and “Church” in this newly recovered manuscript. The premise underlying both, derived directly from Locke, was that God endowed humans with their rights and ensured their honesty through a fear of punishment in the afterlife.

Such matters might be considered interesting historical anachronisms, but some contemporary politicians seem to think that religious belief should be required for political participation. For example, in his remarks delivered at the University of Notre Dame Law School former Attorney General William P. Barr, stated approvingly that the framers of the U.S. Constitution believed “free government was only suitable and sustainable for a religious people.” “Religion,” Barr asserted, “helps frame moral culture within society that instills and reinforces moral discipline.” “Secularism,” Barr averred, had led to “grim consequences”.

While the Founding Fathers made no explicit statement that religion was a prerequisite of citizenship in the Declaration of Independence or the U.S. Constitution, their Lockean arguments entirely depended upon such a supposition, and they may simply have assumed it without feeling the need to assert a truth they could suppose was universally acknowledged. After all, freedom of religion is not freedom from religion. On such a reading of history, disbelief would be fundamentally un-American — alienating, at a stroke, the roughly one fifth of the current US population who identify as atheist, agnostic or nonreligious.

Certain state-sanctioned religious restrictions in the U.S. endured well into the modern era. It was only in 1961, in deciding Torcaso v. Watkins, that the Supreme Court ruled Maryland’s requirement that public officials swear their belief in God a violation of guaranteed constitutional rights. And it was only in 1997 that South Carolina’s Supreme Court followed the federal precedent and held that Article VI, section 2 of the South Carolina State Constitution (“No person shall be eligible to the office of Governor who denies the existence of the Supreme Being”) and Article XVII, section 4 (“No person who denies the existence of a Supreme Being shall hold any office under this Constitution”) were unenforceable, as they were in conflict with the Constitution of the United States. It was thus more than 300 years after Locke drafted the first Constitution of Carolina that religious requirements were finally nullified in one of its successors. But while these provisions are now considered infeasible, they remain in place, and South Carolina is one of the seven US states whose Constitutions still purport to ban atheists from office. It wasn’t until 2016 that President Barack Obama signed legislation extending protections against religious persecution to people with non-theistic beliefs, including those who do not subscribe to any religion at all.

The recovery of this new Locke manuscript serves to remind us that deep historical currents flow beneath the surface of today’s political debates — the present is merely those parts of the past that have not yet been worn away. Locke’s legacy, for good and ill, lives with us still. ♦

J. C. Walmsley is an Editor for the Clarendon Edition of the Works of John Locke and a Senior Director of Customer Experience and Innovation Consulting at Publicis Sapient.

Recommended Citation

Walmsley, Craig. “Locke, Toleration and Political Participation – A New Manuscript.” Canopy Forum, December 10, 2021. https://canopyforum.org/2021/12/10/locke-toleration-and-political-participation-a-new-manuscript/.