Crimesploitation: Crime, Punishment, and Pleasure on Reality Television

by Paul Kaplan and Daniel LaChance

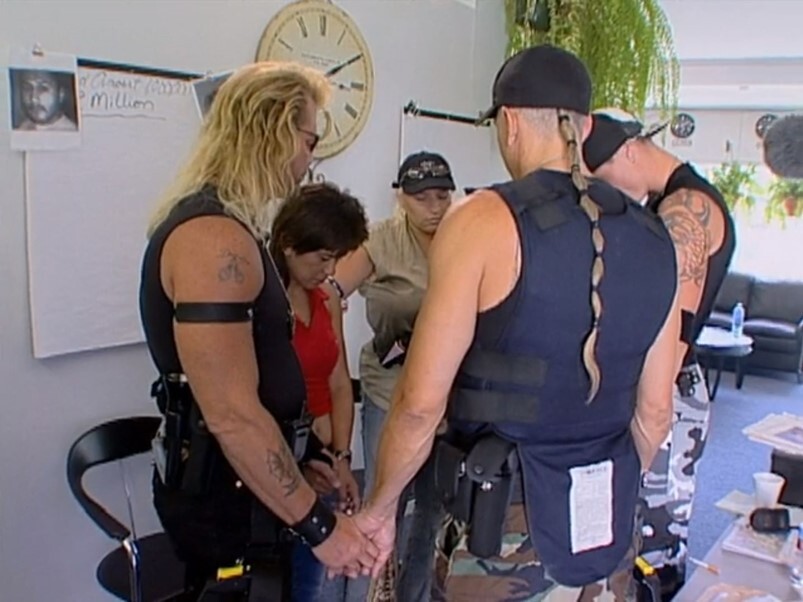

No reality television program about crime and punishment satisfied a hunger to see inmates as redeemable more than the A&E network’s most watched show, Dog the Bounty Hunter. Over the course of 246 episodes that aired from 2004 to 2012, the show chronicled Duane “The Dog” Chapman running his family business, Da Kine Bail Bonds, on the Hawaiian island of Oahu with his girlfriend Beth (who became his wife in 2006), some of his adult children (he has twelve children from four marriages), and his fictive kin (most notably, a man named Tim “Youngblood” Chapman who is identified as Dog’s brother but is of no blood relation to Chapman). Drawing up to three million viewers per episode, the family chased down men and women who had violated the conditions of their bail. After they caught their prey and before they handed them over to officials at the local jail, however, they engaged in quick, backseat-of-the-SUV counseling sessions aimed at transforming their fugitives’ lives. Dog popularized an evangelical Christian response to those who commit crime, one that sought to balance justice with compassion.

Most half-hour episodes of the show follow the same basic plot. At the beginning of every episode, the Chapmans discuss the fugitive they are planning to capture as dangerous and imagine his or her capture with a bit of sadistic delight. They describe the fugitive as polluted (“dirt,” “scumbag”), subhuman (“bitch,” “tiger”), or pathological (“liar,” “dangerous”). The fugitive is a pollutant, “matter out of place,” as anthropologist Mary Douglas would put it, and the bounty hunter a heroic handler of toxic waste. In one episode, one of Dog’s associates hopes that the fugitive will try to flee arrest: “If this guy don’t run can we tell him to run? ’Cuz I gotta work out some kinks, man.” The hunt then begins when the family piles into their SUVs and heads out to find their fugitive. As they act on tips and move from one location to the next, members of the family take turns making adrenaline-stimulating statements to the cameras and one another, producing anticipation of an exciting, risky, and dangerous physical confrontation. When it eventually comes, the take-down is often a small-scale degradation ceremony. “In Donald Trump’s words, ‘You’re fired!’” Dog gleefully says to one fugitive he has just apprehended.

Once the excitement of the capture dissipates, the tone changes dramatically. With the fugitives in handcuffs (“cuffs of love,” as Dog calls them in one episode), disgust gives way to empathy. Initially imagined as an animal (“tiger,” “lot lizard,” “wolf”) or a monster (“wolf man,” “Dracula”), the fugitive becomes a vulnerable human being (“girl,” “kid”), a family member (“sister,” “brother,” “Dad,” “daddy”) or an equal (“brah,” “friend,” “man”). The Chapmans move from hunters to therapists, their prey from hardened criminals in need of punishment to troubled men and women in need of help. In the backseat of their SUV, Dog and Beth Chapman offer their captured fugitives cigarettes, ask them about their lives and their struggles with drugs, and give them hope of a future in which their spiritual, physical, and economic needs are met.

Family figures prominently in these backseat conversations. To convince offenders to sin no more, the Chapmans impress upon them their obligations to their kin, especially their children. In one episode, a fugitive named Tim gets into a shouting match with his girlfriend’s mother, who is present at his apprehension. Dog intervenes by appealing to the man’s love for his daughter: “How much do you love that baby girl?” Dog asks. “That’s my world right there,” Tim replies. “Then let’s prove it, from this day, this second on.” The family unit, the show insists, is the foundational source of economic security and social order. The implication is that love for family — in contrast to, say, living wage jobs — is the ultimate form of crime prevention. Tim, like most suspects, appears moved by the efforts made by the bounty hunters. He cries. He promises to change his ways (“I swear on my skin, everything,” Tim says). And he thanks his captors for their kindness. “I should have listened to everyone from the start,” he admits, demonstrating a submission to the moral order he had treated with contempt earlier in the episode. He is rewarded with hope. “You’re getting rebuilt, refurbished, rehabilitated,” Dog says to him. After this counseling session, the Chapmans take their prisoner to jail and hand him over to the state.

The implication is that love for family — in contrast to, say, living wage jobs — is the ultimate form of crime prevention.

Much of the power of these scenes comes from Dog’s discussions of his own sinful past, which landed him in a Texas prison at the age of twenty-six for murder. Dog frequently shares, with fugitives and the show’s audience, the story of his own transformation from wayward criminal to fatherly bounty hunter. In these scenes the show works to popularize what American Studies scholar Tanya Erzen has called the “testimonial politics” of evangelical Christians. With its emphasis on an individual decision to follow Jesus as the route to salvation, evangelicals have historically deployed testimonies, “narratives of sin, redemption, and personal transformation,” that aim to convince listeners that God’s grace extends to all who seek it. The testifier often confesses their own sinful past before describing a transformative experience in which they heard God’s voice or felt his presence. The unspoken logic underlying testimonials is that government shouldn’t be in the business of trying to make people into good citizens. Personal and social wellbeing requires a spiritual and familial grounding that the state can never provide. Dog’s testimonies reflect this conservative ideology and aim for a similar rhetorical effect.

But the state does have a role to play. If the bounty hunter is the potter, the fugitive the clay, and the backseat testimonial-exhortation a kind of reshaping of the fugitive into a new form, jail is the kiln in which the fugitive’s new self sets. It cannot be avoided. In one of his many testimonials, Dog explains that the experience of being stripped of individuality in prison can prompt a moral awakening:

One of the things about going to prison is that you don’t have a name anymore. You have a number. So it was the day I got my number and they said, “From now on you’re no longer called the Dog. You’re 271097.” At that second, I said, “This is it. I’m now going to be the Dad that my Dad raised me to be.”

The experience of losing one’s self, of becoming a number, Dog suggests, prompts an openness to change that previously did not exist. Ultimately, the degradation of incarceration is linked to a “tough love” approach to shaping behavior that has influenced everything from parenting guides to addiction treatment programs. By accompanying the capture and caging of persons charged with crimes with a dose of testimonial politics, Dog spiritually justifies the violence visited upon these fugitives. Incarceration is represented as a constructive force rather than an act of deprivation that has devastating social, political, and economic effects on offenders and their families.

In Dog popular messages about the criminal justice system seem aimed at satisfying a desire to see punishment as a generative, compassionate act.

In depicting its heroes as compassionate rebels and their antagonists as rebellious sinners, Dog reveals something about how punitiveness was popularized in the early twenty-first century. It did not always appeal to a vision of criminals as beasts or vermin who deserve nothing but scorn. In Dog popular messages about the criminal justice system seem aimed at satisfying a desire to see punishment as a generative, compassionate act. Criminals, Dog aimed to reassure its viewers, are not garbage to be thrown away. They can transcend their demons — addiction, self-hate, an internalized sense of impotence — and emerge from a period of suffering with a sense of self-possession.

The Problem of Hope

Why, we might ask, was a show like Dog — with its surprisingly tender treatment of captured “bad guys” — popular? Why do other reality television shows like Lockup and Lockdown similarly humanize those who are locked up?

We suggest that a certain amount of optimism about offenders is required to make harsh punishment palatable to the public. In his study of why punishments change over time, cultural sociologist Philip Smith writes of a pattern. Forms of punishment flourish when the public perceives them as “eliminating the disgusting and unruly, effecting the decontamination of the spiritually and morally offensive, banishing evil, and enforcing cultural classifications and boundaries.” Support for a punishment falters, conversely, when confidence in its ability to do these things declines. “When punish ments put out more cultural pollution than they are deemed to eliminate, they are in trouble.” Prisons, Smith notes, have been susceptible to charges that “the potentially virtuous [prisoners] were all too easily contaminated by contact with vice.” Maximum-security facilities that separate and keep prisoners in their cells around the clock have also run into problems; they “have come in turn to be seen as factories of disorder churning out madmen and making unpredictable evil recidivists from petty criminals.” Nonetheless, the prison has never become so tainted in the public imagination that it was abolished. It has instead subsisted for over two centuries on a balance of pessimism and optimism — the darker assumptions about criminal incorrigibility tempered by the optimistic idea that prisons can be places where the wayward turn their lives around. Cynicism and hope work together to protect the prison’s reputation as a punishment that controls, rather than contributes to, moral pollution.

Crimesploitation prison shows reflect and reinforce this balance of skepticism and hopefulness about incarcerated people. If they only depicted prisons as warehouses for the violent and the incorrigible, shows like Dog, Lockup, and Lockdown would risk undermining our most cherished ideas about humanity: that we are moral beings, endowed with the capacity to transcend our animality. The inclusion of stories of inmates growing and redeeming themselves and authorities showing care and compassion for those they cage work to ward off nihilistic feelings about the prison.

The inclusion of stories of inmates growing and redeeming themselves and authorities showing care and compassion for those they cage work to ward off nihilistic feelings about the prison.

Hope also works on a psychological level. Numerous studies have measured the punitive response humans have toward people who have behaved unjustly. They have found that retribution — a desire to “get even” — motivates our desires to punish. Our urge to punish wrongdoers persists even when punishment won’t make us safer or happier. But punishment can be satisfying, researchers suggest, when we receive feedback from the punished person that she has experienced a positive moral change in response to the punishment. When participants in one experiment punished fellow players of a game who had abused a position of advantage, one study found that the “satisfaction” they received from meting out the punishment was directly proportional to the degree to which the offender endorsed the moral message the punishment was trying to convey. Hearing “I deserved this punishment” can make the punishment seem meaningful and worthwhile. By offering audiences hope about the future of at least some of the people held in the nation’s jails and prisons, Dog may have made satisfying what otherwise might have come to seem pointless. A defining feature of the age of mass incarceration is not simply the magnitude of punishment, but its invisibility. Those convicted of crime disappear shortly after their sentencing, sometimes forever, leaving the public with few options for observing whether the punishment has had any kind of moral effect on the criminal. In this context Dog, offers a surrogate solution to this problem. Presenting stories of offenders responding morally and spiritually to their punishment, these shows may make the pain of punishment visible and meaningful, and thus satisfying, for viewers. But degradation does not catalyze rehabilitation. Those who leave the prison are not elevated back into some noble humanity, but physically, politically, and socially disfigured by the experience. ♦

Paul Kaplan is Professor of Criminal Justice in the School of Public Affairs at San Diego State University. He is the author of Murder Stories: Ideological Narratives in Capital Punishment and the co-author of Crimesploitation: Crime, Punishment, and Pleasure in Reality Television. His Twitter handle is @pauljkaplan.

Daniel LaChance is Winship Distinguished Research Professor (2020-23) in the Department of History at Emory University. He is the author of Executing Freedom: The Cultural Life of Capital Punishment and the co-author of Crimesploitation: Crime, Punishment, and Pleasure in Reality Television. His Twitter handle is @dwlachance.

Recommended Citation

LaChance, Daniel and Kaplan, Paul. “Excerpt from Crimesploitation: Crime, Punishment, and Pleasure on Reality Television.” Canopy Forum, August 4, 2022. https://canopyforum.org/2022/08/04/crimesploitation-excerpt