Iran’s Political Agenda: Women’s Bodies at the Intersection of Religion and Law

Faegheh Shirazi

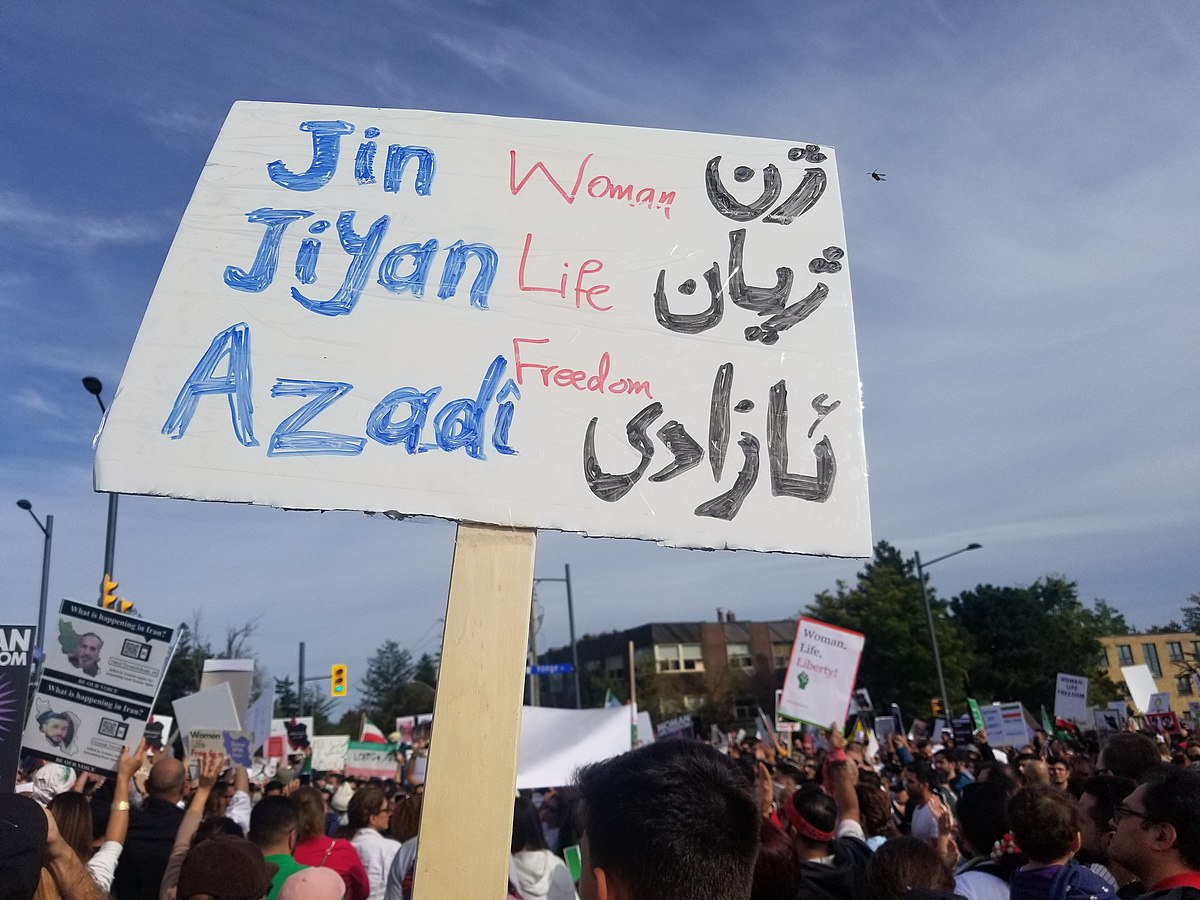

A sign with “Woman, Life, Freedom” (Jin, Jiyan Azadi) in Central and Northern Kurdish by Pirehelokan (CC BY-SA 4.0).

As a scholar in the field of Islamic studies and material culture since the early 1990s, I have continually read and written about veiling and the hijab in Muslim cultures. In Iran, the hijab has had a rocky relationship with women’s rights, relating to ownership of the body and the enforcement of religious doctrine as law. Indeed, there is no secret that Iranian women have been used as pawns by religious and political institutions for specific agendas, sometimes in contradictory ways depending on the historical era, at times forced to unveil, at other times forced to veil.

In 1936, Reza Shah’s Kashf-e hijab ordered the unveiling of women by force, accompanied by the claim of modernizing and “empowering women.” In 1979, when Ayatollah Khomeini toppled the second Pahlavi Shah, one of the first visible changes was the forceful veiling of women, claiming the “empowerment of women” by re-instituting their honor and dignity. The hijab as a subject matter is deep because, in addition to religious arguments for its existence, it has also assumed many other purposes across a wide field that include sociology, politics, performing arts, poetry, literature, economics, and fashion.

Shi’i Islam is the official religion of the Islamic Republic of Iran. According to statistics provided by the current Iranian government in 2020, 90-95% of Iranian people are followers of the Twelver Shi’i doctrine. Shi’ism in Iran has been the official religious doctrine since the sixteenth century. In 2020, Sunni Iranian Muslims accounted for 10% of the population, made up of some Kurds, Persian Lari, almost all the Iranian Baluchis, Turkomans, a small group of Arab-Iranians, and a small community of Persians in Khorasan and the southern region of Iran. The Islamic Republic of Iran has, unfortunately, failed to properly integrate its Sunni population into its political system, depriving them of higher political positions. Since the start of the Islamic Republic in 1979, no Sunni has served as a government minister or governor, even though the Iranian constitution does not ban Sunnis from holding ministerial appointments. A number of Sunnis adhere to spiritual Sufi orders Qadiriya and Naqshbandi: “Salafist ideas have also gained a foothold among Iranian Sunnis, especially in the last two decades. Like their counterparts in other countries, Salafists in Iran tend to advocate an ultra-conservative brand of Sunni Islam. Nevertheless, many Iranian Sunnis follow a moderate understanding of religion.”

Christianity, Judaism (the second-largest Jewish community in the Muslim World), and Zoroastrianism are officially recognized and protected, and these minorities have reserved seats in the Iranian parliament. While Bahaism has the largest non-Muslim religious minority, Baha’is are not recognized by the Islamic Republic of Iran as,“ Iranian authorities have brazenly imposed a system of discrimination and oppression against the Baha’is.” The United Nations has repeatedly accused Iran of persecuting citizens based on their religion and depriving Iranian women of the equal freedom granted to men.

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution of Iran, the hijab became compulsory in public and enforced on every woman, regardless of their religious following. The government justifies the imposition of the hijab for women by drawing on parts of the Qur’an, particularly the following two verses:

“And enjoin believing women to cast down their looks and guard their private parts and not reveal their adornment except that which is revealed of itself, and to draw their veils over their bosoms… (Qur’an 24:31)

“O Prophet! Tell your wives, daughters, and believing women to draw their cloaks over their bodies. In this way it is more likely that they will be recognized [as virtuous] and not be harassed. And Allah is All-Forgiving, Most Merciful.” (Qur’an 33:59)

However, in addition to the Qur’anic verses, with their history of disputed interpretations, several recorded sayings (ahadith) of the Prophet Mohammed are used to enforce the veiling. Debates continue on whether all women should veil or if veiling is meant only as a recommendation. Iran’s compulsory hijab law is enforced on every female citizen and non-citizen, such as tourists or foreign officials, during their stay in Iran regardless of their own religion. This means that all women in public view must observe the hijab regulations. Additionally, the government encourages women to adopt the most conservative form of the hijab, i.e., the maqnaeh, a one-piece head covering made of plain fabric in dark colors covering the chest and back shoulders, and a long one-piece chador worn over it. As an encouragement to wear what the government proclaims is the ideal hijab, the simplest design with dull colors and limited choices is offered at an inexpensive price. However, such efforts to clothe Iranian women have not captured the attention of a younger generation with very different tastes and who do not want to wear what the government calls the “real hijab.” The young generation is more interested in wearing what is labeled by the government as the “westernized hijab,” called variously the “loose hijab” (shol hijab), “improper hijab” (bad hijab), or “without hijab” (bihijab), in addition to other derogatory and insulting definitions. Propaganda policies by the Islamic Republic of Iran equate these insulting definitions, for the most part, to the Western way of life.

Iranian Government: Specific Ideological Agendas

The imposition of veiling for women since 1979 has resulted in many harsh treatments for women in Iran when “…political-ideological considerations influence cultural legitimation.” According to the Islamic Republic of Iran, the ideal woman must wear the traditional coverage advocated not only as a religious obligation but also as a duty towards the Islamic government of Iran.

At the beginning of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979, the hijab was enforced by authorities who did not hesitate to physically and mentally punish women for not veiling. Disobedient women were charged with the crime of being an infidel or other illicit charges such as prostitution and had to pay a fine to be released from jail. During the Iran-Iraq war that lasted from 1980-1988, women at times were treated even more harshly for wearing what was deemed an “improper/bad hijab.” For example, when the Iraqi military advanced into Iranian borders, the government tightened its grip on the hijab issue. The woman and her hijab made headlines in every government-controlled media rather than news of the advancement of Iraqi armed forces into Iranian territory. This diversionary focus on the hijab was one of the strategies used by the government to distract the nation from the reality of what was happening in the war.

This diversionary focus on the hijab was one of the strategies used by the government to distract the nation from the reality of what was happening in the [Iran-Iraq] war.

The preamble to the Iranian constitution expressly forbids any sector to use a woman’s image in commercial ads for services and/or goods and assigns the first duty for women as motherhood. The Islamic Republic of Iran managed, effortlessly and without resistance, to use images of veiled women to further very specific ideological agendas including making money, such as using images of veiled women on postage stamps. Suddenly images of veiled women sprang up everywhere, seemingly of infinite variations on specific themes. In every Iranian city, on every building, inside all businesses, outside and inside public transportation facilities, and in every educational institution, the private and “sacred” woman of Iranian culture was transformed into a public image for all to view.

Indeed, Iran’s government sanctioned the public’s right and duty to gaze upon these images of women, all of which were either calling men to war, demonstrating strong support of the war, and/or modeling the proper style of hijab. During this era, the hijab became a universal symbol of the chaste and pious Iranian daughter, sister, wife, and mother. In 1983, an amendment was added to the Iranian constitution stating that women who harmed public chastity by appearing without religiously sanctioned veiling in the streets and in public view would be subject to receiving up to 74 lashes. On September 16, 2022, the shocking news of the death of Mahsa Jina Amini, a young Kurdish-Iranian woman arrested for not wearing a “proper” hijab, angered the entire nation, particularly young women who were similarly in danger and as vulnerable as Mahsa Amini. Mahsa’s death came about under suspicious circumstances, believed to be caused by hard blows to the head while in police custody.

Iranian women have always played a prominent role in political protests throughout the Qajar dynasty (1789-1797) to the present, for example in the Green Movement (Green Wave of Iran), which began in June of 2009 relating to disputed election results and lasted until the earlier part of 2010. Women actively participated and showed their support for the movement by wearing green veils, wrapping green ribbons on their wrists, and painting part of their face green.

Mahsa’s death triggered the most recent uprising known as Woman, Life, Freedom (Zan, Zendegi, Azadi). We are witnessing the deep anger of Iranian citizens, particularly women, about Iranian governmental policies, in particular regarding the compulsory hijab ruling passed in 1983. In Woman, Life, Freedom, which began in September 2022, many young women were the driving force behind protests demanding an end to the forced hijab, the strict dress code, and an end to the inequality of genders. These young women protesters became the target of Iranian governmental brutality. This uprising is supported by ordinary people who are usually the primary victims of such unfair political, economic, and civil rulings. During the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, women of all ages, particularly the younger generation, were on the front lines marching. Ironically, while the United States always claims to be the champion of human rights, the U.S. government and its media were silent for the first three months into the movement. During this silence, many young Iranian people were brutally killed, injured, or hospitalized due to police violence and brutality.

During the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, women of all ages, particualrly the younger generation, were on the front lines marching.

Because the control and censorship of the media by the Iranian government are well known, ordinary people do not believe in national Iranian news and TV (Seda va Sima). People generally get their news on the uprising from private citizens who risk their lives to deliver news content, revealing the brutality of government agents who may be in plain clothes and easily blend into the crowds. According to numerous private clips, shot live during the events and from many different parts of Iran, there is no doubt that police are randomly shooting at people and targeting victims’ eyes with shotgun pellet birdshot, enforcing an order authorized by the leaders to create fear in the hope that the protestors would evacuate the streets. According to Amnesty International, “Security forces unlawfully fired live ammunition and metal pellets to crush protests, killing hundreds of men, women, and children and injuring thousands.”

Many of the protesters were arrested and placed in prisons around the country without a legitimate and legal trial, the presence of a defense lawyer, or sufficient time to prepare a defense letter. Many were sentenced to death by hanging within a month or two of their arrest. In most cases, the victims were accused of the crime of being anti-government, which automatically rendered the victim anti-Islam, punishable by death. The protestors, in fact, were using their civil rights to express their disappointments and the unhappy life they were experiencing under the current Iranian government, a dictatorship under the pretense of an Islamic theocracy.

The sentencing of political prisoners is handed down by judges who are strongly opposed to any individual who dares to question the policies running the country. Many of the protestors in such courts are accused or sentenced on dubious charges. The prisoners who are waiting for their trials are physically and mentally abused. Sexual abuse of the young is well documented. Various tortures are used to extract fake confessions. After so many young men and especially women perished, were injured for life, or committed suicide after being released from prison, Iran finally captured international attention and the women of Iran were named “Heroes of the Year” by TIME magazine in 2022.

Obtaining accurate statistics on the number of political prisoners in Iran is not an easy task. However, according to the U.S. Department of State:

“…security forces killed more than 500 persons, including at least 69 children, and arrested more than 19,000 protesters, including children, according to the nongovernmental organization Human Rights Activists News Agency. Some of those arrested faced the death penalty, including children. The government also routinely disrupted access to the internet and communications applications to prevent the free flow of information and to attempt to interrupt or diminish participation in protests.”

While the death of Mahsa Jina Amini created anger, particularly in her home state of Kurdistan, people around Iran came out in public demonstrations, protesting forced veiling and the dictatorial behavior of the Islamic Republic. Women not only removed their veils publicly to show their hair, but many cut their hair to show sympathy for the cause. In older Iranian traditions, short hair on a woman held negative connotations, while cutting the hair short, particularly in regions of Kurdistan and Lorestan, is associated with mourning. There is a saying in Kurdish: Wa gise dalegam ghasam. It translates to mean: “I swear by my mother’s hair,” since a woman’s hair is considered sacred.

Public chanting of “Death to Khamenei1,” burning veils, singing, and dancing in the streets are some of the forms of protests by civilians in Iran, who faced harsh reactions from the police. Young and school-age girls became the targets of beatings, shooting in the eyes and face, and being gassed while in school buildings. The first wave of poison gas in a girl’s school was reported on November 30, 2022, in the city of Qom. Golnar Motevalli reported on April 11, 2023: “A new spate of suspected poisonous-gas attacks has hit Iranian girl’s schools in several towns and cities this week after authorities said they had arrested scores of people over earlier incidents. Attacks come as police vow crackdown on women who shun hijab.” In the earlier stages of the incidents, the government publicly stated that the girls’ illness was related to anxiety and possibly some other form of illness they might have contracted. Later, the Iranian Health Ministry reported that toxicologists had identified the substance responsible for poisoning the victims as nitrogen gas: tasteless, odorless, and not visible.

In Iran, hair is politicized. The government controls people’s bodies, both women’s and, to a lesser extent, men’s. The government monitors the public behavior of women in part by issuing dress codes and keeping a watchful eye on women in public. In his recent public speeches, the Iranian supreme leader Ali Khamenei has openly issued a threat warning that if a woman removes her hijab, she is guilty of haram (forbidden by Islam) behavior, will be identified by spy cameras, and then arrested. Women defied the threat by removing their hijabs and posting selfies on social media for all to see. Khamenei then ordered that businesses deny service to unveiled women, otherwise their business will be shut down. In this way Khamenei expects ordinary people to spy on their fellow citizens. This new law also states that women who refuse to wear head coverings in public places or inside their cars will face court trials and have their vehicles impounded. The Iranian government is trying to frighten its citizens into submission. Khamenei’s recent order to deny service to unveiled women was not welcomed by business owners who are losing customers and their livelihoods. Agents of the government are now arresting the business owners, some of whom are ignoring the order and, after a warning, finding their businesses burned down in different parts of the country. Reaction to the burning and destroying of shops backfired, as the business owners have gone on strike and closed their shops.

Despite the hardships they face from their repressive government, the Iranian women continue in defiance to post their unveiled images on social media, even though it is a well-known fact that their public images can be identified by government agents who can charge them with a hefty load of criminal accusations. The oppressive bodily regulation always caused some reactions and responses by women of Iran. In the recent history of Iran, there have been several movements started by women to express their unhappiness toward state laws that control their bodies and clothing. They continue to limit their movements, freedom of choice, and, most of all, promote a mandatory, divided society with women as second-rate citizens.

The latest civil unrest and protests against the government of Iran, in response to the death of Masha Amini in police custody, reveal a groundswell of support for women’s rights. Will the old, hard-line leadership be replaced by leaders more closely aligned with the protestors? The Amini protests began on September 16, 2022, and are ongoing as of this writing, July 2023 – comprising more than 10 months. It is hard not to believe that the length and persistence of the current protests are laying the groundwork for the inevitable liberation of women’s rights in the future.♦

Faegheh Shirazi is a professor in the Middle Eastern Studies Department at the University of Texas at Austin. She has published five books, and numerous scholarly articles. Her latest publication is Islamicate Textiles: Fashion, Fabric, and Ritual (Bloomsbury, May 2023). In addition to her scholarly activities, she is also a painter and surface textile (patched work & embroidery) artist. Her artwork has been selected for several of her book covers.

Recommended Citation

Shirazi, Faegheh. “Iran’s Political Agenda: Women’s Bodies at the Intersection of Religion and Law.” Canopy Forum, August 4, 2023. https://canopyforum.org/2023/08/04/irans-political-agenda-womens-bodies-at-the-intersection-of-religion-and-law/