Defining a Muslim; The Case of Pakistan and its Ahmadis

Yasser Latif Hamdani

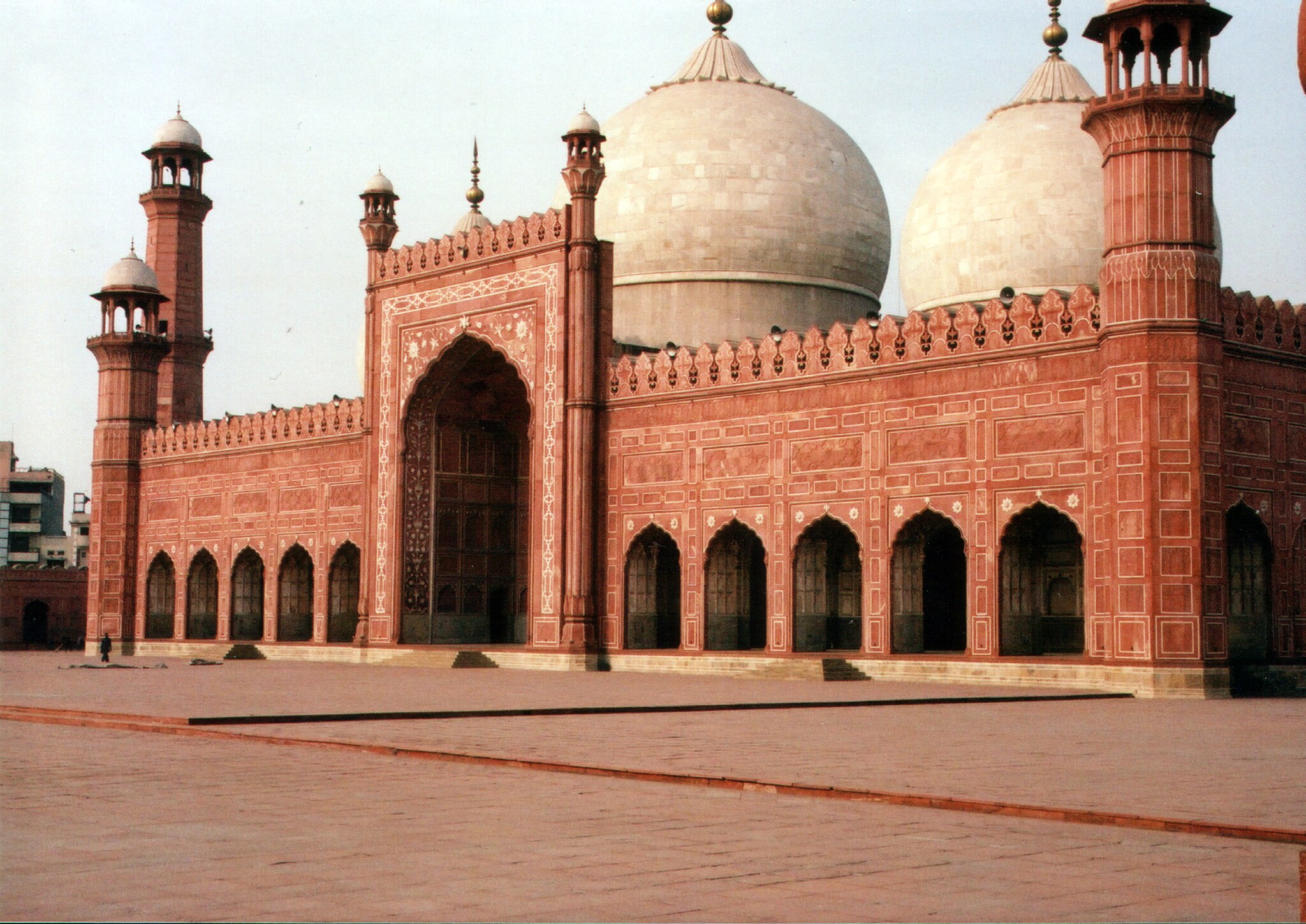

Main chamber of Badshahi Mosque by User:Amjad.m (CC BY-SA 3.0)

On January 16th, 2025, the government of Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province, demolished a historic Ahmadi mosque in the city of Daska. This mosque was built by Zafrullah Khan (1893-1985), Pakistan’s first foreign minister and one of the founding fathers of the country. This is ironic, considering that religious freedom was one of the inherent promises made by the Pakistani government during the nation’s founding in 1947. Religious freedom is a fundamental right granted to citizens under Article 20 of the Constitution of Pakistan; the Constitution promises that, subject to law, every citizen has the right to profess, practice, and propagate their religion. However, since 1984, the right guaranteed by this clause has been denied to Pakistan’s Ahmadi community, as they can neither profess, practice, nor propagate their faith as they see fit. In 1974, Pakistan’s parliament passed a constitutional amendment to officially declare the Ahmadis as Non-Muslims. The Prime Minister at the time, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, gave in to the demand, and the amendment was passed unanimously.

Almost thirty years earlier, the movement to declare the Ahmadis Non-Muslims predated independence and was in full swing during the 1940s. The move mightcould have succeeded Pakistani independence and the closing days of the Raj if not for personal intervention by future first governor-general of Pakistan Mahomed Ali Jinnah’s, as he prevailed over his colleagues and others in scuttling the action. Jinnah (1876-1948), then a leading constitutional lawyer, understood the legal implications of defining a Muslim and what it would mean for the citizens of Pakistan. During their now-famous correspondence in 1944, Gandhi asked Jinnah to define his understanding of the term “‘Muslim,”’ but Jinnah refused, saying that a “‘Muslim”’ was anyone who was ordinarily understood to be or seen as a Muslim. Muhammad Ali Jinnah had a long and influential political career, advocating for Muslim political rights, constitutionalism, and self-determination, which ultimately led him to become the first leader of Pakistan, independent of British rule, in 1947. On the eve of the creation of Pakistan, Jinnah promised that religion would not become a state issue and that Pakistan would not be a theocracy that determined issues of faith for its citizens. To drive home this point, Jinnah appointed Zafrullah Khan, a leading Ahmadi member of his party, as the first foreign minister of Pakistan, overruling objections made by the orthodox Muslim community in the young country. The demand to get the Ahmadis declared as Non-Muslims was renewed again in the 1950s, when a group of religious parties started the movement to get Zafrullah Khan removed from the position of foreign minister. The riots that followed led to the formation of an Inquiry Commission. The resulting report, known as the Munir Report, warned against the dangers of any attempt to define what it means to be Muslim. The Munir Report influenced the framers of the 1956 Constitution to purposefully exclude a definition of the term “‘Muslim,”’ despite having reserved the office of President for Muslims. During this time, the idea of what it meant to be Muslim was primarily centered on cultural, not theological, markers. This is why Iskander Mirza, the first president of the Pakistani Islamic Republic as an independent country and a nominal Muslim at best, was elected to the Presidency without objection.

Significantly, the Constitution of 1956 did not establish a state religion. However, all of this changed with the Constitution of 1973, as it not only established Islam as the state religion, but also reserved the office of the Prime Minister (in addition to the President) for Muslims only. The movement to excommunicate the Ahmadis from the definition of “‘Muslim”’ was raised again in 1974, and, this time, the ruling PPP and opposition NAP parties(both left-leaning and supposedly secular parties) voted together to pass the constitutional amendment. The focus of this amendment was theological in nature, building on the controversial “‘Khatm-e-Nabuwat,”’ or the Finality of Prophethood Doctrine. They argued that, since the Ahmadis believed in a prophet after Muhammad, they were outside the pale of Islam. The Ahmadis believe in a doctrine that states that, although the Quran posits that Muhammad was the last law-bearing prophet, new prophets can continue to appear because Allah has not stopped talking to man. The Ahmadis hold that the founder of their community, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, was the promised Messiah foretold by all Abrahamic traditions and that he had come to renew the Islamic creed and free it from impurity. This idea militates against the mainstream Sunni Muslim belief in the second coming of Christ as the foretold Messiah.

In 1984, the government of General Zia ul Haq, the military dictator who overthrew Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s government, promulgated an ordinance that banned the Ahmadis from “posing” as Muslims or preaching their faith, and this was punishable by three years imprisonment. This law was upheld as constitutional by the Supreme Court of Pakistan in the1993 case of Zaheeruddin v State (1993 SCMR 1718), which relied on 19th-century US jurisprudence, specifically around the Morril Bigamy Act of 1862 and Mormon issues. The Court held that the Ahmadis’ mode of worship was not protected by the ‘freedom to profess, practice, and propagate’ clause of Article 20 in the Pakistani Constitution; the Court argued that, in any event, these rights are subject to law, and were therefore validly proscribed by the ordinance.

“Posing” as a Muslim could mean a variety of things, and over the last four decades, the Ahmadis have been jailed for using the Islamic greeting, having Muslim names, calling their places of worship ‘mosques,’ possessing a copy of the Quran, celebrating the Muslim festival of Eid, or even eating meat during Eid. In Allaha Wasaya v Federation of Pakistan (PLJ 2018 Islamabad 316), Justice Shaukat Aziz Siddiqui directed the government to ensure that the Ahmadis amend their last names on their National Identity Cards by adding Mirzai (a derogatory slur), that they should be made to wear clothes that distinguish them from orthodox Muslims, and that they should be barred from government jobs. The wide net cast by this judgment opened the floodgates for further persecution and marginalization of the Ahmadi community in Pakistan. The National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) now requires the Ahmadis (and other religious minorities) to first declare themselves Non-Muslims in order to be eligible for National Identity Cards. While a judgment of the Sindh High Court in the Har Lal case (PLD 2024 Sindh 100) (in which I served as counsel) tried to rectify this, this discrimination remains on the books. In alignment with the judgment from Allah Wasaya v Federation of Pakistan, the Tehreek-e-Labaik Pakistan Party has been campaigning to have Ahmadi mosques demolished for possessing architecture similar to that of “Islamic” mosques. Countless Ahmadi places of worship have been razed in Pakistan by the government, especially in the provinces of Punjab and Sindh. Scores of Ahmadi citizens are now behind bars for possessing “Muslim” names, and many of them have been charged with the offense of “possessing a Quran.” The Lahore High Court held that Ahmadi mosques built before 1984 do not need to be razed, but that has not stopped the authorities in Pakistan from doing so, like in the case of the mosque at Daska.

In an opinion authored by Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, the Supreme Court of Pakistan stated the following when issuing judgment in the Tahir Naqqash case (PLD 2022 SC 385):

“Article 260(3) of the Constitution declares the Ahmadis/Qadianis as non-Muslim, it neither disowns them as citizens of Pakistan nor deprives them of their entitlement to the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution. The Constitution treats, safeguards and protects all its citizens equally, whether they are Muslims or It non-Muslims. Article 4 of the Constitution is an inalienable right of every citizen, including minority citizens of Pakistan, which guarantees the right to enjoy the protection of law and to be treated in accordance with law… Article 20(a) of the Constitution provides that every citizen shall have the right to profess, practice, and propagate his religion subject to law, public order, and morality. Article 20(b) provides that every religious denomination or sect shall have the right to establish, maintain and manage its religious institutions. Under Article 22, the Constitution provides that no person attending any educational institution shall be required to receive religious instruction or take part in any religious ceremony or attend religious worship if such instruction, ceremony or worship relates to a religion other than his own. Article 22(3)(a) provides that no religious community or denomination shall be prevented from providing religious instruction for pupils of that community in any educational institution maintained wholly by that community or denomination.”

In 2024, the matter came before the Supreme Court again, where it held that Ahmadis had the right to profess, practice, and propagate their faith in the privacy of their homes and places of worship. Unfortunately, under political pressure, the Supreme Court has since reviewed this judgment and reversed its earlier dictum. As of today, the Ahmadis are prohibited from enjoying the right to freely exercise their faith, even within the confines and privacy of their homes and places of worship. Arguably, this brings about fears of cultural genocide, along with the looming fear of actual genocide being perpetrated against the Ahmadis, as religious extremists from the Barelvi School of Islam have begun to dig up the graves of Ahmadi citizens and exhume their dead bodies while under the watchful eye of the authorities.The future of the Ahmadi community in Pakistan is bleak, and it is not made better by the fact that the Ahmadis are actively discouraged from participating in national elections. While all other citizens of Pakistan, including other religious minorities, are placed on a single electoral list, a separate list containing Ahmadi citizens is used to suppress their votes and keep track of their addresses. Thus, the Ahmadis are disenfranchised because, in order to vote, they must first renounce their own creed and declare themselves Non-Muslims. In 2017, the government made an ineffective attempt to undo this discrimination, but it was soon rolled back under pressure from the clerics. ♦

Yasser Latif Hamdani is a human rights barrister and author from Pakistan, specialising in freedom of religion under the Pakistani constitution. As a lawyer he has represented civil society organisations and religious minorities in Pakistan before the High Courts of Pakistan. He is also the author of the book Jinnah: A Life (Pan Macmillan 2020).

Recommended Citation

Hamdani, Latif Yasser. “Defining a Muslim; The Case of Pakistan and its Ahmadis.” Canopy Forum, March 12, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/03/12/defining-a-muslim-the-case-of-pakistan-and-its-ahmadis/.

Recent Posts