Constitutions Address Religious Freedom, but Not as Much as Desired

Dennis Petri and Jonathan Fox

The Village Lawyer by Pieter Brueghel (US-PD).

The following essay is reprinted and adapted on Canopy Forum in collaboration with the journal Derecho en Sociedad, a biannual electronic publication that is free and open access. Their issue 19(1) features full length articles in Spanish and English. Read Petri and Fox’s long-form essay on Constitutions Address of Religious Freedom here.

See other essays in this series here.

Although constitutions are often overlooked in practice, making them unreliable indicators of actual religious freedom, the widespread inclusion of religious freedom clauses in these documents underscores the enduring legitimacy and significance of religious freedom in global politics. Even if many countries may disregard these clauses in practice, the fact that they find it necessary to pay lip service to the concept underscores its considerable standing in world politics. In other words, most countries feel compelled to at least pretend that they provide religious freedom. China serves as a notable example, with its constitution explicitly guaranteeing religious freedom under Article 36. However, the reality of religious freedom within the country often falls short of these constitutional assurances.

In this essay, we take a closer look at what national constitutions say about religious freedom, and explore their practical significance. To achieve this, we rely on the RAS-Constitutions dataset that was recently updated by the Religion and State Project at Bar-Ilan University.

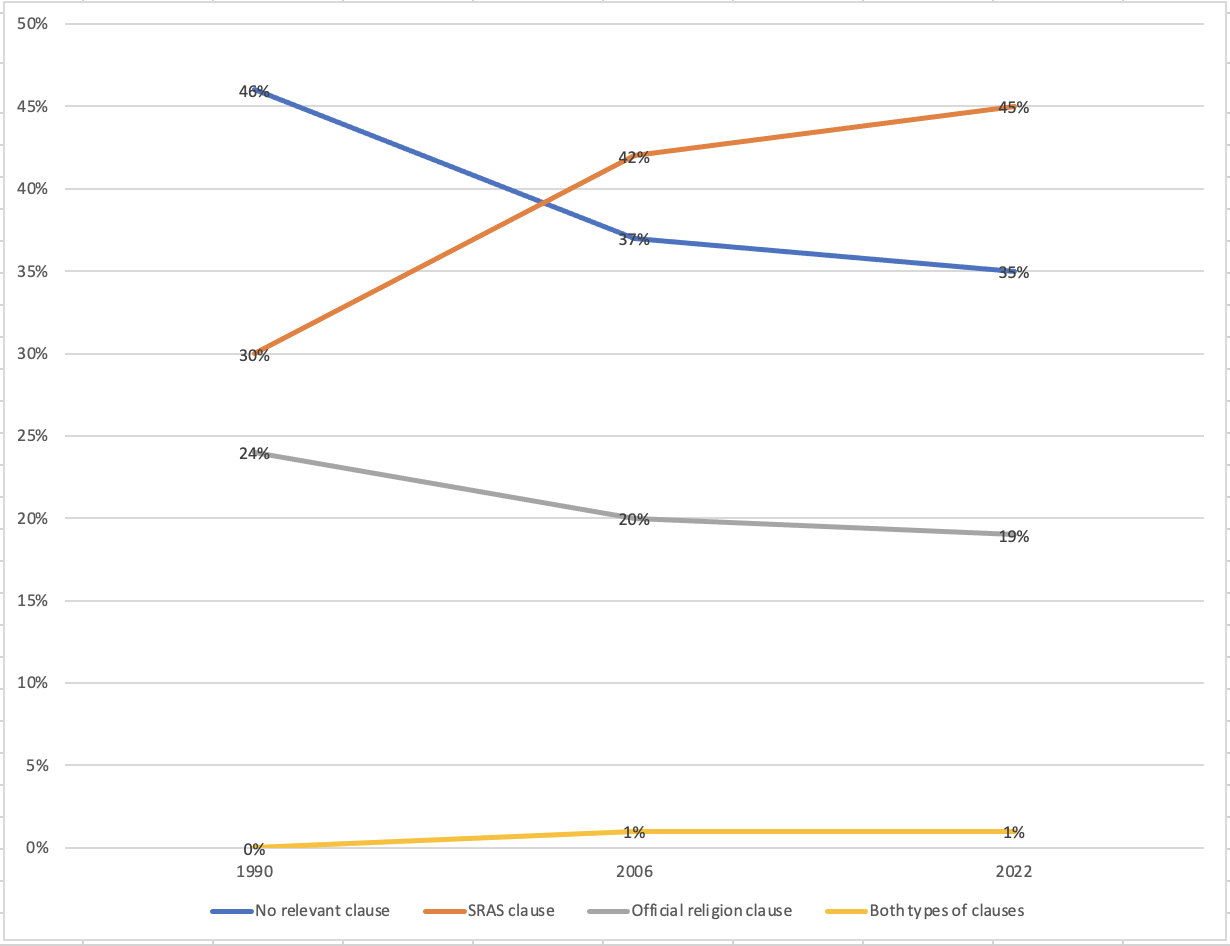

Graphic 1. Official Status of Religion (1990, 2006, 2022)

As can be expected, constitutional clauses regarding religion tend to remain stable over time, even when countries adopt new constitutions. The main variation in the data took place shortly after 1990, when a historic number of new countries were created, most of which following the dismantlement of the former Soviet Union. Between 2006 and 2022, changes were minor.

A few trends can be observed. First, even though the percentage of countries that do not have a relevant status of religion clause in their constitutions decreased between 1990 and 2022, it increased in absolute numbers. Second, the percentage of countries with an official religion clause decreased slightly, while the percentage of countries with a Separation of Religion and State (SRAS) clause increased more significantly, suggesting a growing consensus on the importance of the principle of separation of religion and state. Finally, the odd country that has both an official religion clause and an SRAS clause is Bulgaria (Art. 13), a country that both establishes Eastern Orthodox Christianity as the country’s “traditional” religion, but also establishes SRAS.

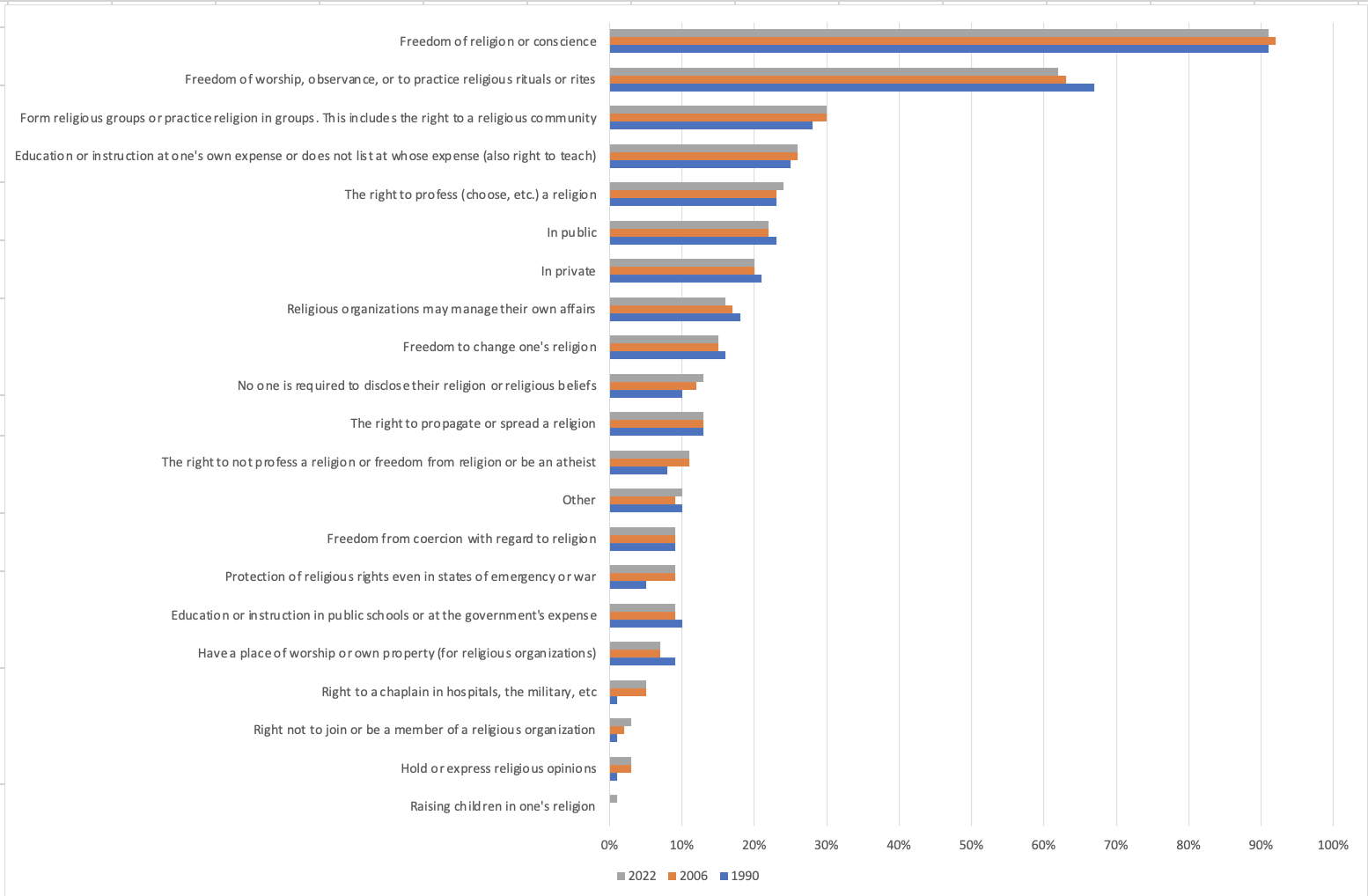

Graphic 2. Religious Freedom Clauses (1990, 2006, 2022)

As shown in graphic 2 on religious freedom clauses, there is a large degree of variation among the 21 variables tracked by the RAS-Constitutions dataset. More than 90% of the countries in the world have a constitution that guarantees freedom of religion or conscience. Roughly two-thirds of the countries have a constitutional clause that protects freedom of worship, observance, or practice of religious rituals or rites. The remaining 19 variables occur less frequently, only appearing between 1% and 30% of national constitutions in 2022.

In some countries, the alternative descriptors of religious freedom are used instead of the plain protection of freedom of religion, suggesting that religious freedom is only partially respected, especially if they also include qualifications of religious freedom, a set of variables that we leave out of this study. For instance, Panama’s constitution upholds religious freedom, but stipulates that the “Christian morality and public order” must be respected (Article 35). Constitutional scholars within the nation find the interpretation of this clause to be ambiguous and open to debate.

In other countries, several descriptors of religious freedom are used in combination, which suggests a broader constitutional protection of religious freedom. For example, some may explicitly state that the right to change one’s religion or to proselytize is protected. As an illustration, India explicitly protects the right to “propagate religion” in Article 25 of its Constitution.

The Limited Significance of Official Religion and Separation of Religion and State Clauses

As is true for many policy fields, there often is a gap between what constitutions say, and the reality on the ground. This is also true for religious policy. As we discuss below, the analysis of constitutional protections for religious freedom cannot be considered a sufficient proxy for religious policy. In order to truly understand religious policy, a more holistic approach is necessary to account for lower legislation that complements constitutional provisions, as well as government practices.

To begin, whether a country has an official religion or not, is not a good indicator of the overall state of religious freedom. Countries with an official religion are relatively rare, as only 34 (out of 176) countries had such a clause in 2022, though a few additional countries declare official religions extra-constitutionally. The countries that do have an official religion are very heterogeneous. They include democratic countries such as Costa Rica, Denmark or Israel, but also authoritarian theocracies such as Afghanistan, Iran and Saudi Arabia, which are all listed as Countries of Particular Concern (CPC) by the US Commission on International Religious Freedom. We thus conclude that having an official religion, is not, per se, incompatible with the religious freedom of minority religions.

In 2022, 80 countries had a SRAS clause. When considering SRAS clauses, we are faced with a similar heterogeneity like that among countries with an official religion, as not all forms of separation are the same. As Fox clearly describes in his 2015 book Political Secularism, Religion, and the State, a whole typology of secular states can be developed with varying implications for religious freedom. To keep the analysis simple, two general types of political secularism can be distinguished: a form of secularism that is in practice antireligious and a form of secularism that is neutral toward religion. In other words, SRAS can be both a friend and an enemy of religious freedom. The United States would be an example of a neutral, and perhaps even accommodating, form of political secularism, whereas countries like France, Mexico (although a bit less since constitutional reforms in 1992), and Turkey (at least until 2003) could be categorized as anticlerical.

In both cases, whether a country has an official religion clause or a SRAS clause does not say much about the overall state of religious freedom. To understand the overall state of religious freedom, it is necessary to consider actual religious policy, and specifically look at the nature and level of the involvement of the state in religion, as well as state practices of favoritism of the majority religion and discrimination of minority religions.

The Difference between Religious Freedom Clauses and Actual Religious Policy

Even when religious freedom finds its place within a constitution, this alone proves to be insufficient. The refusal to allow freedom of religion in constitutional texts cannot even be considered as a glaring red flag. The following countries do not include any mention of religious freedom in their constitutions: Austria, Comoros, France, Mauritania, and Saudi Arabia. In some of these countries, however, religious freedom is protected by ordinary legislation and through general government practice. Few of the constitutional religion clauses prove to be robust indicators of Government Religious Discrimination (GRD). The most reliable predictors of GRD are not constitutional causes, but other variables such as autocracy, tangible state support for religion, and societal religious discrimination (SRD) against religious minorities.

Fox finds that the lack of correlation between most constitutional religion clauses and GRD, coupled with the capacity of other religion-related variables to predict GRD, implies that these clauses provide a suboptimal measure of a country’s genuine policies and attitudes toward religion. Even when official religion clauses in constitutions predict GRD with marginal significance, it is the practical levels of state support for religion that consistently predict GRD. As previously mentioned, constitutional support for an official religion barely influences GRD unless it reflects a practical commitment to a state religion. Fox further indicates that religious freedom clauses, including qualifications and protections for specific religious freedoms, exhibit no discernible indirect influence on GRD. Their consistent failure to predict GRD underscores their status as common constitutional rhetoric that may or may not be applied in practice.

What holds true for GRD is equally applicable to SRD. We can employ a contrario reasoning by examining some highly significant cases. According to the Violent Incidents Database of the International Institute for Religious Freedom, which tracks incidents of violence against religion by systematically analyzing media sources and other public information, Nigeria consistently ranks as the country with the highest number of violent incidents related to religion, with the majority perpetrated by non-state actors. This is in stark contrast with Nigeria’s ostensibly favorable constitution regarding religious freedom. Another illustrative example pertains to many Latin American states, which boast excellent religious freedom provisions on paper but still grapple with some degree of SRD. This underscores that constitutional provisions do not guarantee the protection of religious freedom by the state.

Why Constitutions’ Promises Often Fail to Protect Religious Freedom

In the complex landscape of religious freedom, there is a puzzling discrepancy between the lofty promises enshrined in constitutions and the actual respect for religious freedom on the ground. Several factors contribute to this disconnect.

Firstly, it’s crucial to recognize that many constitutional clauses pertaining to religious freedom are often symbolic in nature and lack any practical implications. This paradox does not apply to religious freedom only, but to other human rights as well. It is well-known that authoritarian states adopt constitutional structures, establish parliaments, and conduct elections, seemingly embracing democratic norms while undermining them in practice. They do so for many reasons, but most of the time this is window-dressing, i.e. a way to provide a fig leaf of democracy.

Secondly, a substantial number of restrictions on religious freedom find their place not within constitutional texts but in lower-level legislation, bureaucratic practices, or remain concealed within various legal measures. One prominent example is the presence of blasphemy laws, which can severely limit religious expression and freedom in many countries, but are rarely included in national constitutions.

In this complex landscape, a multidimensional perspective on religious freedom is key. Indeed, religious discrimination also manifests itself beyond the purview of legal analysis. Indeed, even when religious rights are protected by constitutions and other legislation, religious groups may also be subject to a variety of human security threats that at first sight have nothing to do with the free exercise of their religion, but that actually constitute an alternative form of discrimination. For example, most religious groups in Cuba enjoy freedom of worship, but that does not mean they have full religious freedom. They are often hindered in ways that, at first glance, have little to do with religious freedom: they may be accused of violating zoning laws because religious services are often held in houses, as permits for the construction of places of worship are rarely granted. Additionally, religious leaders critical of the regime may be accused under fabricated charges.

Lastly, the dissonance between the legal framework’s promises and their practical implementation is a classic issue within the international human rights system. The capacity of the international human rights system to get states to enforce human rights, including the right to religious freedom, is limited by the principle of national sovereignty, which often implies there are no guarantees that constitutional and international human rights commitments, including to religious freedom, are respected in practice.

The Constitutional Clauses that do Matter for Religious Freedom

Alternative constitutional clauses may wield more substantial influence over religious freedom. Clauses denouncing religious hate speech and safeguarding the right not to have a religion tend to correlate with higher GRD levels when coupled with anti-religious forms of secularism.

The clauses within constitutions that significantly influence GRD do not pertain to central declarations of a state’s relationship with religion or its commitment to religious freedom. Instead, they focus on more specific religious matters, which may not be perceived as the primary indicators of religious freedom in constitutional texts. Specifically, clauses safeguarding the right not to profess a religion and those banning religious hate speech both demonstrate a noteworthy association with higher levels of GRD. This observation suggests that these clauses better represent an anti-religious form of secularism compared to constitutional declarations of a state’s secularity.

The prohibition of religious hate speech may appear reasonable on the surface, but its potential implications can be complex. It raises questions about the interpretation of religious texts that criticize other religions, potentially categorizing them as hate speech. Furthermore, any limitations on speech, including hate speech restrictions, have illiberal connotations, challenging the principle of free speech essential to liberal philosophy and governance. These restrictions tend to be vague and open to interpretation, posing a risk to religious and other fundamental freedoms.

Additionally, clauses protecting the right not to profess a religion may signify a desire to shield secular or non-religious individuals from religious influence, potentially reflecting a fear or distrust of religion. This protection is often present in states with substantial societal discrimination against religion, suggesting that this concern largely arises from a non-religious perspective.

Furthermore, among the countries with such clauses, several are former Communist states where anti-religious aspects of Communist ideology still exert influence, indicating a correlation between this protection and anti-religious sentiments rooted in history. Therefore, understanding secularism as a political ideology requires distinguishing between positions advocating for state separation from religion and those promoting anti-religious agendas. This differentiation is crucial for analyzing the complexities of secularism’s various facets in constitutional contexts. ♦

Dennis P. Petri, PhD is the International Director of the International Institute for Religious Freedom and Founder and scholar-at-large of the Observatory of Religious Freedom in Latin America. He is a Professor in International Relations and Head of the Chair of Humanities at the Latin American University of Science and Technology and the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences. He is the author of The Specific Vulnerability of Religious Minorities, a book on undetected religious freedom challenges in Latin America.

Jonathan Fox (Ph.D. in Government & Politics, University of Maryland, 1997) is the Yehuda Avner Professor of Religion and Politics at Bar Ilan University in Ramat Gan Israel. He has published over 100 academic articles and 15 books on various topics in religion and politics including government religion policy, religious conflict, religious minorities, and religion in international relations. His most recent book is Religious Minorities at Risk (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Recommended Citation

Petri, Dennis & Fox, Jonathan. “Constitutions Address Religious Freedom, but Not as Much as Desired.” Canopy Forum, March 27, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/03/27/constitutions-address-religious-freedom-but-not-as-much-as-desired/.

Recent Posts