Police Abolitionisms: Political Goals and Religious Ideals

Charles Guth III

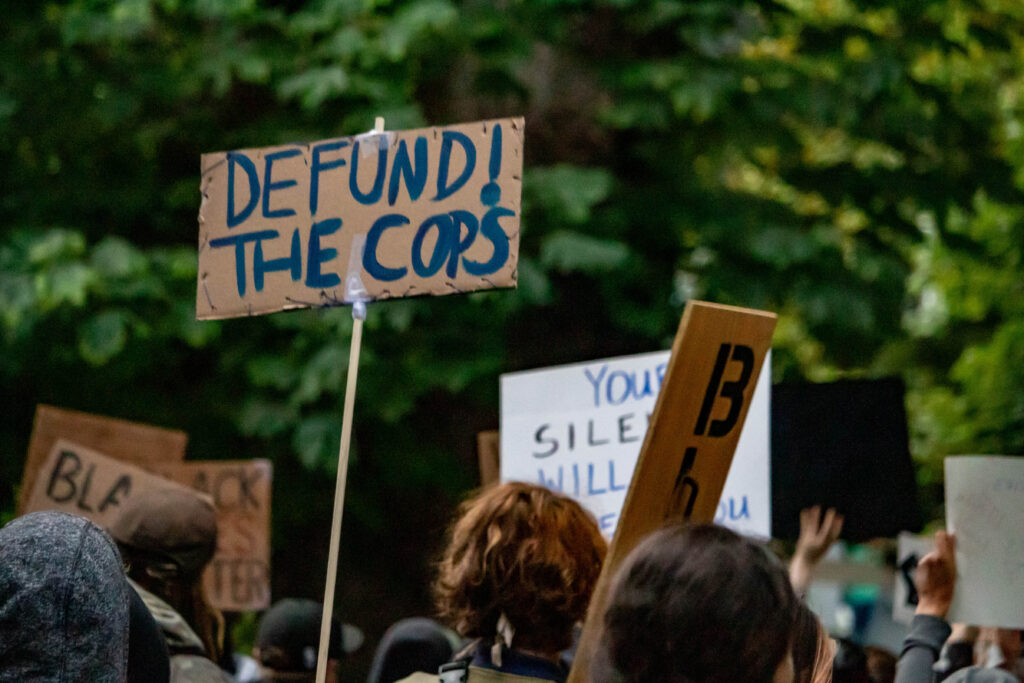

Image by David Geitgey Sierralupe on Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The United States has a policing problem. American police have killed over 1,000 people each year for the past decade and kill at a far higher rate than police in any other wealthy democracy. They use force on over 300,000 people per year, injuring approximately 100,000 of them per year. As the torrent of high-profile cases over the past decade illustrates, a disturbing amount of this violence is morally unjustifiable. Further, Black and Latinx people are disproportionately subject to police violence. They are also more likely than average to be stopped, searched, or arrested. Despite the good intentions of many police officers, then, American policing is excessively violent and systemically racist.

A growing number of citizens and activists claim that the solution to this problem is not to reform police forces, but to abolish them. They point not only to the prevalence of police brutality and the shocking extent to which American police are unaccountable for misconduct, but also to the failure of moderate police reforms such as increased use of body cameras. According to police abolitionists such as Andrea Ritchie and Mariame Kaba, reforms do not work because the underlying function of American police is and has always been to oppress poor and racially minoritized people. The only way to end unjust policing, they conclude, is to abolish the police.

Unsurprisingly, police abolitionism is highly controversial. Most Americans oppose efforts to defund or abolish the police, and such efforts are criticized as naive even by some progressives. According to these critics, police are needed to prevent violent crime and to secure public safety.

As is so often the case in American politics, the debate surrounding police abolitionism is influenced by both race and religion. White Christians overwhelmingly support the police. Approximately 80% of them express high levels of trust in police officers, compared to 61% of the general public and only 32% of Black Christians. Duke University historian Aaron Griffith has shown that many white Christians read the Bible to teach that God has ordained the police to prevent crime and punish criminals. In this, they stand in a long tradition of Christian thought that claims God authorizes civil governments to use coercion and violence to curb the harmful effects of human sin.

Other Christians are moved by their faith to pursue police abolition. Some are inspired by the Black Church’s tradition of activism and ideology critique; others, by Roman Catholic social teaching; still others, by the Anabaptist tradition of pacifism. As a theologian and Christian ethicist, I am struck by the fact that some Christians passionately believe that their faith requires abolishing the police, while others passionately believe that it requires supporting police officers and institutions.

Because the debate surrounding police abolitionism is so polarized, one might expect it to be clear what abolitionists seek. But that is not the case. Different people mean different things by the call to abolish the police. I therefore want to step back from the debate and consider various forms police abolitionism can take. Doing so will demonstrate that different versions of abolitionism bear different burdens of proof and stand in different relations to religious commitments. But I also hope it will facilitate a more productive conversation between police abolitionists and reformists.

Meanings of “Abolish”

Given its name, it can be tempting to think of police abolitionism as an entirely negative project, but most abolitionists also have an ambitious positive goal. They seek to transform society by creating programs and institutions that eliminate (as far as possible) the root causes of serious crime and violence. These include poverty reduction programs, universally accessible mental health and drug addiction treatment, and community-based safety initiatives. Abolitionists claim that social changes such as these would render the police obsolete and that police could then be abolished.

But what do abolitionists mean when they call for the police to be abolished? This is not as clear as it might seem. The call to abolish the police is often associated with the call to defund the police, but these terms are ambiguous. Some people use “defund” to refer to the goal of shrinking the size of police forces, while reserving “abolish” to refer to the goal of eliminating them completely. Others, however, treat “defunding” as equivalent to “abolishing” the police.

Furthermore, abolitionists do not all mean the same thing by the term “abolish.” Tracy Meares’s, a Yale law professor, claims that “[p]olicing as we know it must be abolished before it can be transformed.” Meares’s statement implies that we can “abolish” the police without eliminating them, so some abolitionists have criticized her for watering down their rhetoric. But even the prominent abolitionist Alex Vitale has said that he does not know whether we can ever eliminate the police. Perhaps for this reason, a recent “Note” in the Harvard Law Review states that “[t]he movement for police abolition seeks to eliminate, or massively downsize, American policing.”

We can therefore distinguish different versions of police abolitionism depending on how they understand the term “abolish”: a strong version that seeks to eliminate the police and a modest version that seeks only to significantly reduce the number of police officers and (presumably) the range of social problems police are used to address.

Meanings of “Police”

No matter how we understand “abolish,” assessing police abolitionism requires a clear definition of “the police.” If the goal is to abolish the police as such, and not merely this or that police department, we need to know what institutions and agents count as “police.” But this is also not as clear as it might seem.

Some writers specify what they mean by “the police” through history. They claim that the police are an early nineteenth-century invention, one that originated with Robert Peel’s model for the London Metropolitan Police or the development of well-organized slave patrols in Southern U.S. cities. These historical accounts implicitly define police through a set of institutional arrangements: professionalization, a military-like system of ranks, and so forth.

We might doubt whether this way of defining the police is well-suited to police abolitionism, however. Abolitionists are primarily concerned about the injustices police perpetrate, not the institutional forms they take. Suppose that a quite different institution—say, a loosely organized all-volunteer group—fulfilled roughly the same tasks and functions as current police forces. In that case, there might not be any police in the above sense, but abolitionists would not be satisfied with this result.

Abolitionists need another definition of the police, then—one that focuses more directly on the activities and injustices they oppose. For example, they might define the police as any institution with legal authority to use physical violence to enforce domestic laws. This definition would apply to a wide range of institutions and agents, and thus lead to an expansive understanding of the goal of abolishing police.

Alternatively, abolitionists could define the police by reference to forms of policing that produce most of the injustice they oppose, such as “hotspot” policing, traffic stops, drug raids by SWAT teams, and so forth. “The police” could then be defined as the institutions or agents who perform these activities. Such a definition would be less encompassing than the definition in the previous paragraph. For example, it would not necessarily apply to cybercrime units or officers that provide security at government buildings. So this definition would lead to a more restricted understanding of the goal of abolishing police.

Burdens and Benefits

We have seen that versions of police abolitionism vary according to how they understand the term “abolition” and how expansively they define “the police.” Recognizing as much helps us appreciate that different forms of abolitionism bear different burdens of proof and have different relative strengths.

One benefit to the more modest and restricted versions of police abolitionism is that they seek less sweeping changes than the stronger and more expansive versions and are therefore less vulnerable to certain objections. For example, the common claim that police are necessary to secure public safety, and the theological claim that God ordained police for this purpose, do not as such say anything about how many law enforcement officers or what kinds of units society needs. This is an additional, largely empirical question. And abolitionists are happy to argue on empirical grounds that the U.S. would be better off with less and very different law enforcement than it currently has.

Modest and restricted versions of abolitionism come with their own problems, however. In ordinary usage, “to abolish” typically connotes eliminating something. And when we think of “police,” we typically think of all the agents and institutions we currently call police, not an especially violent or morally dubious subset of those. It seems likely, then, that the average citizen will interpret calls to abolish the police as calls to eliminate everything we currently call police, which is a very unpopular idea. So if self-described abolitionists are not committed to that idea, it would seem prudent to distance themselves from it. Perhaps it would be wiser to refer to their position as radical police reformism. Most Americans believe the police need some reforms, so this designation would allow activists to argue that effective reform of the sort most citizens already seek simply requires more far-reaching changes than citizens typically assume.

Stronger and more expansive versions of police abolitionism benefit from a rhetorical clarity that the more modest and restricted versions lack. But given the higher burden of proof they bear simply because they call for more sweeping changes, why would someone embrace them? Wouldn’t it be more reasonable to adopt a gradual, ameliorative approach and see if less sweeping changes suffice to end systemic police brutality and racism?

The best answer to that question, I think, appeals to an ethical ideal according to which any social order that relies on police is inherently dubious or at least sub-optimal. If someone accepted this ideal, they would have reason to desire a society without police simply out of principle. What interests me, as a theologian, is the way Christian doctrine lends support to such an ethical ideal and what this can tell us about police abolitionism more generally.

Abolition as an Ideal

According to traditional Christian conceptions of salvation, when the kingdom of God is fully realized, there will be no injustice or violence. God’s kingdom is characterized by perfect peace. But the best justification for having police officers who may use violence to enforce the law is the need to mitigate serious injustice and violence. So, in traditional Christian theology, there will be no police in God’s kingdom. Now, according to many Christians, God calls humans to work to bring current society into nearer conformity with God’s kingdom. And that seems to lend support to a strong version of police abolitionism.

Some Christians will object to this argument that although there will be no violence and no police in God’s kingdom, humans cannot establish its perfect peace—only God can. It would therefore be unreasonable for us to pursue police abolition as a political goal. In response, Christian abolitionists could dig in and insist that we can bring our societies into near enough conformity to God’s kingdom to justify eliminating the police. But they could also shift how they conceive of police abolition. They might come to regard it less as a concrete political goal and more as a regulative ideal that shapes which concrete goals they do pursue. On this view, the ideal of a society like God’s kingdom, which has no need for police, can continually inspire us to create social arrangements that are less dependent on policing and violence to secure justice.

One needn’t be a Christian to regard police abolition as a regulative ideal, of course. Anyone with a moral vision of an ideal society that has no need for recourse to coercion or violence can adopt this standpoint. Doing so can motivate them to imagine solutions to social problems that do not rely on police, and that can expand the range of options we consider in political deliberations. Treating police abolition as a regulative ideal could therefore contribute to real political change.

Conclusion

The debate over police abolitionism often proceeds as if calls to abolish police all mean the same thing. But there are many versions of police abolitionism. These vary according to how they define abolition, how they define the police, and whether they treat police abolition as an achievable goal or a regulative ideal. Recognizing this can facilitate more productive conversations about how to fix America’s policing problem. It can help us identify common ground between those who adopt modest or restricted versions of abolitionism and those who seek to reform the police but who recognize that prior reform efforts have been too moderate. It can also help those who think police abolition is unrealistic as a political goal appreciate how it can serve as an ideal that can help society reduce its reliance on policing. ♦

Charles Guth III is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Princeton Theological Seminary. His academic work focuses on the interconnections of Christian theology, ethical theory, and social justice.

Recommended Citation

Guth III, Charles. “Police Abolitionisms: Political Goals and Religious Ideals.” Canopy Forum, April 24, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/04/24/police-abolitionisms-political-goals-and-religious-ideals/.

Recent Posts