Constitutionally Enshrined Parental Rights to Religious Education: A Comparative Analysis

Kento Yamamoto

A Woman Reading by Ivan Kramskoi (PD-Art).

The right and responsibilities of parents regarding their children’s religious education form a foundation of religious freedom. In many legal systems, this right is considered an implicit component of the broader freedom of religion or right to education. However, a specific, explicit constitutional guarantee for parents’ right to religious education is notably rare. A global survey reveals that out of 193 national constitutions currently in force, only 14 contain explicit provisions addressing this matter.

This small number raises some questions: What is the significance of enshrining this right explicitly in a nation’s constitutional law? What do these provisions look like? What commonalities do they share, and how do they differ? In this essay, I embark on a comparative constitutional analysis to explore these questions. By examining the textual features, origins, and potential implications of these 14 constitutional provisions, I aim to elucidate their role in shaping the delicate balance between parental rights and responsibilities, children’s rights, and the state’s role in education.

Global Landscape and Foundational Dataset

The 14 countries whose constitutions explicitly recognize parents’ right to provide religious education are geographically diverse, albeit with notable concentrations in Europe and Africa. The countries are Andorra art. 20 , Cape Verde art. 49(3), Ethiopia art. 27(4), Gabon art. 1(16), Germany art. 7(2), Ireland art. 42, Lithuania art. 26, Philippines art. 15(3), Poland art. 48(1), Romania art. 29(6), Serbia art. 43, Slovenia art. 41, Spain art. 27(3), and Zimbabwe art. 60(3). The provisions from these nations, sourced from the English translations provided by the Comparative Constitutions Project, form the core dataset for this analysis.

To contextualize these national provisions, I look at the foundational international human rights instruments that preceded most of them: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of 1948 and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) of 1966. These documents established early international norms for parental rights to education.

Article 26(3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states as follows: “Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.” This wording emphasizes the primacy of parental choice. In contrast, Article 18(4) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) offers a more detailed formulation: “The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to have respect for the liberty of parents and, when applicable, legal guardians to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions.” This provision focuses on the parents’ liberty to ensure an education aligned with their personal convictions and frames it as an obligation for states to respect.

Given that 13 of the 14 constitutions (with Ireland being the exception) were enacted after these instruments, a central hypothesis is that they were influenced by the UDHR or, more likely, the ICCPR.

Tracing Influence: Similarity Analysis

To test the hypothesis of influence, I conducted a quantitative analysis involving the measurement of the semantic similarity between the constitutional texts. Using Google’s Universal Sentence Encoder, which converts sentences into high-dimensional vectors to compare their meaning rather than mere lexical overlap, I compared the 14 national constitutional provisions, UDHR, and ICCPR. A similarity score exceeding 65% is generally considered indicative of a strong semantic connection. However, the appropriate percentage for relevance can differ across fields. For the semantic similarity of legal texts, there is no universally accepted standard.

The results were illuminating. The Constitution of Serbia (2006) showed the highest average similarity rate (68.2%) to the other documents in the dataset, followed closely by Ethiopia (1994) (67.3%). Notably, the ICCPR ranked ninth (55.9%) in average similarity, whereas the UDHR ranked last (44.7%). At first glance, this suggests that the direct textual influence of these international instruments on national constitutions is weaker than hypothesized.

However, the relatively low score of the ICCPR can be attributed to its characteristic “treaty-style” language, which is framed as an undertaking for “States Parties” rather than a direct conferral of rights on individuals. To investigate this, I conducted a direct comparison between the ICCPR and Serbian constitution, which had the highest similarity score:

Serbia (2006) Article 43: “Parents and legal guardians shall have the right to ensure religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions.”

ICCPR (1966) Article 18(4): “The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to have respect for the liberty of parents and…legal guardians to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions.”

Setting the treaty-style language aside, the core normative content is nearly identical. Both identify parents and legal guardians as the rights-holders and guarantee the same right: to ensure a religious and moral education that conforms to the rights-holders’ convictions. This demonstrates a high degree of normative similarity that the sentence encoder, focused on overall sentence structure, might underscore. Therefore, the ICCPR can be reasonably concluded to have exerted a significant influence on the constitutions that explicitly guarantee this right. However, for the UDHR, which does not use treaty-style language, the finding of its weak influence remains unchanged.

Classification of Parental Rights Provisions

A closer examination of the 14 constitutions reveals several key dimensions along which these provisions can be classified.

Right or Responsibility. Most constitutions (ten constitutions) frame the provision as a right of the parents. Four constitutions—specifically those of Gabon, Ireland, Poland, and the Philippines—frame it as both a right and a responsibility (or duty). This dual formulation underscores the idea that providing such an education is not merely a choice but a parental obligation.

Content. The specific content of the guaranteed right varies, although common patterns emerge. The most prevalent formulation is the right to educate (and/or bring up) children in conformity with the parents’ religion or convictions. This model is adopted by nine countries (e.g., Spain, Lithuania, and Ethiopia) and reflects the influence of the ICCPR.

A second common formulation is the right to choose religious education, found in the constitutions of Andorra, Gabon, and Germany. This phrasing aligns more closely with the UDHR’s emphasis on choice, particularly in the context of schooling. Ireland’s constitution offers a slight variation, guaranteeing the right to provide for religious education “according to their means.” The Philippines presents a unique provision, framing the right within the context of the right of spouses to found a family in accordance with their religious convictions.

Explicit and Implicit Limitations. Parental rights to education are not absolute. The potential for conflict with the child’s own developing autonomy and the state’s interest in protecting children necessitates limitations. Only two constitutions, however, impose direct and explicit limitations on this right.

Poland (1997) Article 48: “Such upbringing shall respect the degree of maturity of a child as well as his freedom of conscience and belief and also his convictions.”

Slovenia (1991) Article 41: “The religious and moral guidance given to children must be appropriate to their age and maturity, and be consistent with their free conscience and religious and other beliefs or convictions.”

These provisions show that the parents’ right to religious education is limited by the child’s maturity and their freedom of religion and conscience.

However, all countries that constitutionally recognize parents’ right to provide religious education, except for Andorra, have constitutional clauses guaranteeing special protections for children or obligating the state to ensure their welfare. For example, the constitutions of Germany and Ireland explicitly regulate situations where the state may intervene in family life if parents fail in their duties. The Irish constitution further specifies that in such cases, the state must have due regard for the “natural and imprescriptible rights of the child” and act in accordance with “the best interests of the child.” This suggests that parents’ right to religious education is also intended to be limited by these general provisions.

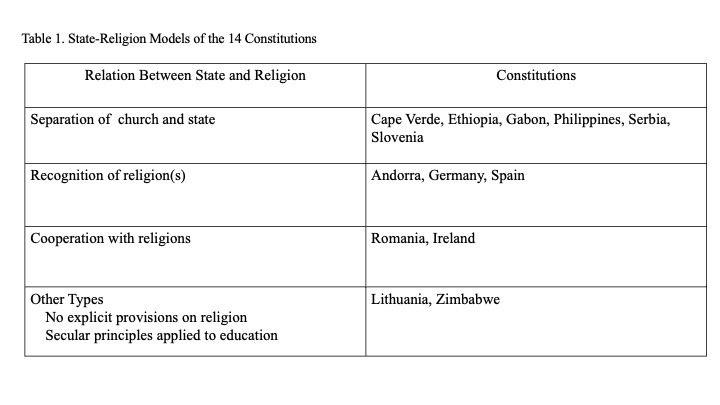

Relation Between State and Religion. My analysis revealed the lack of a strong link between a specific model of state–religion relations and whether a constitution explicitly provides for parents’ right to religious education (see Table 1). The diversity in characteristics of the 14 constitutions suggests that the decision to explicitly protect parental rights in religious education is not determined by whether the state is secular or maintains a relation with religious institutions, but rather by other historical, political, or social factors.

Significance of Explicit Constitutional Provisions

Parental rights to religious education can often be derived from the general freedom of religion or right to education. In many European nations, these rights are well-established in civil codes and other statutes. As Marta Prucnal-Wójcik (2024) notes, “European countries share more similarities than differences regarding the religious education of children within the context of parental responsibility,” often regulated at the statutory level.

Nonetheless, explicit constitutionalization carries at least three significant advantages. First, and most importantly, it provides authoritative guidance for constitutional interpretation and legislation. An explicit clause clarifies the content, scope, and importance of the right at the highest legal level, preventing it from being overlooked or diluted through statutory law or judicial interpretation. It serves as a clear mandate for lawmakers and judges.

Second, it can establish unique rights that are not easily derived from a general freedom of religion clause. The Philippine constitution, for example, links the right to the founding of a family, creating a distinct legal basis. The former constitution of Norway provides a fascinating example. It mandated that adherents of the state’s Evangelical-Lutheran religion were “bound to bring up their children in the same,” transforming a right into a constitutional duty tied to a specific faith.

Third, an explicit provision creates a constitutional framework for coordination and balancing. It forces a direct constitutional engagement with related issues, such as the public education system and rights of the child. Provisions like those in Germany, which connect the right to choosing religious instruction in schools, or in Poland and Slovenia, which mandate respect for the child’s maturity, are prime examples. They integrate parental rights to religious education into the broader constitutional ecosystem, thereby providing principles for mediating the inherent tensions between the rights of parents, children, and interests of the state.

Avenues for Future Research

The explicit constitutional protection of parents’ right to provide religious education, while rare, is a meaningful feature of the legal systems that adopt it. This analysis shows that these provisions are often influenced by the ICCPR and serve crucial functions. They may guide legislation and interpretation, establish distinct rights, and create a framework for balancing competing interests. The varied ways these rights are defined—as a right or a responsibility, with or without explicit limitations—offer valuable models for constitutional drafters and reformers grappling with the relation between family, faith, and the state.

This study is limited to a textual analysis. It opens the door to a host of further empirical and legal questions. How are these constitutional provisions applied and interpreted by courts in practice? Do the outcomes in these 14 countries differ significantly from those in nations where the right is merely inferred from freedom of religion? How does the balance with children’s rights play out in real-world disputes? What can be learned from countries like Japan, where such rights are not clearly defined in either the constitution or civil law? Answering these questions will be essential for a complete understanding of how legal systems across the globe navigate the profound and personal matter of a child’s religious upbringing. This essay is only one step in addressing a larger issue. ♦

Kento Yamamoto is an associate professor at the University of Kitakyushu and a visiting associate professor at Keio University, Japan. He holds a PhD in Law from Keio University.

Recommended Citation

Yamamoto, Kento. “Constitutionally Enshrined Parental Rights to Religious Education: A Comparative Analysis.” Canopy Forum, November 21, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/11/21/constitutionally-enshrined-parental-rights-to-religious-education-a-comparative-analysis/

Recent Posts