Muslim Americans and Citizenship: Between the Ummah and the USA

Saeed A. Khan

Can an individual truly be a citizen of a nation and simultaneously a global citizen? For the 1.8 million Muslims of the world, and especially the estimated 4 million in the United States, the question is deeper than simple political allegiance; it goes to the core of belonging and self-perception. Citizenship, whether as a political imperative or an internalized consciousness, creates identity. Specifically, citizenship allows the individual to be situated within a collective identity. How this identity informs one’s notion of citizenship, or membership within a broader collective may be understood through an examination of the scope and scale of the socio-political entity within which that citizen resides and transacts in citizenship. For many Muslims, this creates what W.E.B. DuBois would describe as dual-consciousness: citizenship to a country of nationality and citizenship to the broader global Muslim collective, the ummah. While this dual identity can be enriching, dual-consciousness may also lead to conflicts over allegiance and the prioritization of resources and emotional investment in connection to a Muslim citizen’s discharging of the rights and responsibilities of political membership.

Much of the current discourse regarding citizenship focuses on the relationship of the citizen to the state. In its simplest form, this relationship involves an individual and a single political entity, i.e. the nation-state. But the nation-state has proved to be a problematic socio-political space for many Muslim.

The concept of the nation-state originated in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War and the Peace of Westphalia, and this particular model is thus based upon a specific European historical context of conflict and compromise. The ensuing development of the individual as a citizen of a state (rather than as a subject to a ruler) sought to reconcile and redefine allegiances to both ecclesiastical and sovereign authorities. The creation of the individual as citizen was the result of a painful, often violent process, one whose ultimate effects are still being negotiated to this day.

For Europeans, the nation-state came about by their own involvement in navigating the turbulent political waters after the Protestant Reformation. By contrast, the nation-state came to the “Muslim world” by way of imposition; Muslims were “given” the nation-state model by way of European colonialism. Thus, they lacked the agency to determine the structure and parameters, let alone the need and relevance of nation-states in Muslim-majority societies. Consequently, the modern Muslim nation-state was, with few exceptions created in the image of European architects, with borders, boundaries and institutions that were dismissive of local, indigenous complexities and concerns. The ensuing evolution of the consciousness of citizenship in Muslim societies became highly contested and convoluted, whether operating within democratic or despotic regimes.

The modern Muslim nation-state was, with few exceptions created in the image of European architects.

Citizenship may be described as a relationship between an individual and the state that involves a mutual exchange of rights and responsibilities. Generally, this exchange is discharged within a single national space. Migration and transnationalism in the 21st century, however, are catalyzing the emergence of individuals with multiple citizenship. They possess legal-judicial relationships with more than one state and thus, are capable of occupying multiple spaces in which the rights/responsibilities interaction may occur. This phenomenon may facilitate the process whereby a citizen may derive the benefits in one state, i.e. where he/she resides and yet fulfill the obligations of being a citizen in another state, or supranational collective, such as a religious community. For example, one may certainly benefit from the citizen’s right to full democratic participation while engaging in the duty to improve society elsewhere, through investment, development and/or charity, provided such efforts are not detrimental to the country in which the individual has citizenship rights.

These developments have complicated previously bidirectional understandings of citizenship. Citizenship no longer consists of an individual’s exclusive relationship with a single political entity. Instead of the conventional reciprocity of rights and responsibility within a single state, we now experience citizenship asymmetrically in ways that redefine the concept beyond its traditional (European nation-state centered) ontological or legal categories. Moreover, tangible impacts on the allocation of resources and their transfer from one state to another by such asymmetric citizens may affect perceptions of national allegiance and loyalty as well as notions of belonging and nationality-based identity.

The phenomenon of bifurcated citizenship rights and responsibilities may best be illustrated by the examples of American converts to Islam, and second- and third-generation Muslim Americans, which are both growing demographic groups in the United States. Converts may be new to Islam but are well situated within America’s cultural and civic landscape, especially as part of their familial heritage. At the same time, members of the latter group who are now in their twenties, thirties and forties, are not immigrants, but they also do not they perceive themselves, nor are they perceived by broader society, as being fully indigenous. Moreover, they do not conform to the traditional definition of diaspora, as they are not dislocated from a central point of ethnic origin. Born in the United States, many of these American Muslims have a connection to their ancestral homelands only through travel and family lore, a connection that plausibly will weaken naturally over time. Affirmed in their identity as U.S. citizens, these Muslim Americans regard their citizenship as not just a political and legal imperative with the state, but also as an elemental extension of their being a full participant in shaping the direction of their society. They are citizens not only for what they do in that capacity, but for the simple fact that they are citizens. At the same time, however, they bear a strong affinity to a transnational or supranational identity: they are citizens of the worldwide Muslim community, or ummah, a new “fraternity” for converts as well.

The Islamic notion of ummah reminds Muslims that they belong to a global community that transcends race, ethnicity, culture, language or class. Irrespective of location or even piety, the connection of being a part of the ummah is a compelling and magnetic force of identity construction. It affirms Islam’s universalistic focus and acts as a deterrent to the potential toxicity of tribalism. In addition, the contemporary fluidity of the Muslim world, with its myriad social, economic, and political instabilities, makes the challenges faced by fellow religionists abroad highly visible to Muslim Americans, even if their own lives may be relatively secure.

The Islamic notion of ummah reminds Muslims that they belong to a global community that transcends race, ethnicity, culture, language or class.

The ummah also typifies the new emerging architecture of globalization, characterized in part by the post-national realignment of borders and identities. Unfettered by political strictures, the ummah resides as a network to which its citizens can maintain an ontological sense of citizenship; they are citizens of the ummah by the mere fact that they are Muslim.

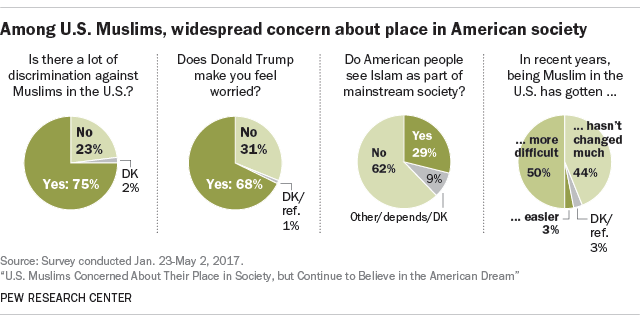

A harmonious relationship between national and religious citizenship, however, is far from being presumptively organic in the lived experiences of many Muslim Americans. Political and cultural discontent may cause a reassessment of how fully or strongly one may self-identify as an American citizen. Similarly, ideological and cultural factors, as well as difficulty coping with the complexities and multivalent challenges of the Muslim world writ large, may result in Muslims retreating from a sense of belonging to a larger collective.

Muslim Americans are hardly unique vis-à-vis their affiliation and identification with a religion on its global scale and also their country of nationality. The push-pull factors inherent in multiple membership may result in a convergence or a clash, depending upon the intensity of a sense of belonging to either or both identities, as well as the equally fluid, even volatile, nature of geopolitics. But being Muslim and American makes the negotiation of citizenship ironically a more accurate reflection of the growing reality of being a citizen of several spaces, including of an ummah and a nation. The complexities of being Muslim-American are not unique to Muslim-Americans. Their efforts in navigating citizenship is a fascinating and important insight for the increasing number of individuals that have such dual identities, whether involving religious, racial, ethnic, national, political, ideological, social or class-based categories. Recognition of this shared, complex engagement with citizenship carries with it the promise of greater understanding among people who share the experience of claiming citizenship in multiple spheres.

Saeed A. Khan is currently in the Department of History and Lecturer in the Department of Near East & Asian Studies at Wayne State University-Detroit, Michigan, where he teaches Islamic and Middle East History, Islamic Civilizations and History of Islamic Political Thought.

Recommended Citation

Khan, Saeed A. “Muslim Americans and Citizenship: Between the Ummah and the USA.” Canopy Forum, October 17, 2019. https://canopyforum.org/2019/10/17/muslim-americans-and-citizenship-between-the-ummah-and-the-usa-by-saeed-a-khan/