An Early Good Friday, at Last:

When Too Many Bells Toll in Italy

Andrea Pin

Photo by Quiritium on Flickr (CC)

An earlier version of this essay first appeared [here] on [Talk About: Law and Religion], the official blog of Brigham Young University’s International Center for Law and Religion Studies.

This article is part of our “Reflecting on COVID-19” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

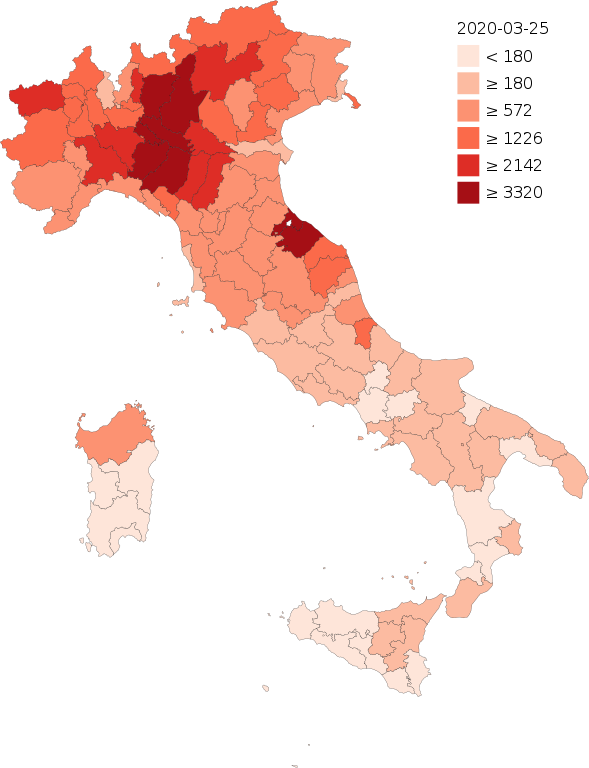

Covid-19 has hit Italy badly. At the time of this writing, the country is dealing with nearly 70,000 coronavirus cases and has suffered over 6,800 deaths from the virus. Like all challenges to the human condition, amidst the suffering and disruptions of the current pandemic there is also opportunity for reflection and growth.

As I explained in a previous essay, the lockdown in Italy has pushed people to find new ways to socialize and practice their faith. From being the primary means of communication only among millennials, the internet has become a viable solution for people of all ages. Meanwhile, people chitchat from their balconies. It has become so popular that at fixed times each day, people routinely stop tele-working, cooking, or watching Netflix, or whatever else they were doing to go to their windows and sing together. They may even flash-mob together only to clap and cheer up. The result has been a transgenerational blending of technology with old-fashioned window-to-window conversation. Media, opinion-makers, politicians, and social media influencers keep encouraging people to stay home and reassuring them that “#wellbefine” (“#andratuttobene”).

The blend of technological and vintage civic rites that have spontaneously developed are not blasphemous, inappropriate, or wrong. But they are facing two formidable challenges. Time—and death.

Even as some areas and younger generations have stubbornly resisted or shown indifference, the government has introduced more restrictions. Very few economic activities remain open, with the exceptions of food shops and newspaper sellers. Public parks have been closed, so citizens are barred from even strolling around. The new limitations mean deeper economic losses and more uncertainties for many families. But the worst news is that these measures are likely to last. We’ll easily spend Easter in isolation, and schools may not resume until May—if they reopen before September at all. The earliest lockdowns were introduced in the Northern regions in late February; by May, many Italians will have spent nearly two months in almost total isolation. How long can we hold our breath?

Of course, political controversies and debates around the virus and its casualties have mushroomed these days. Many find explanations for Italy’s record-high number of victims in government’s lack of preparation, and others blame local bodies, the ineffective health strategy that governments adopted, or Italy’s relatively older population demographics. But such arguments cannot cope with what Italian TV is broadcasting every day. The blog post I wrote some ten days ago spoke of 1,000 deaths. By the time it was released, the number had increased to 2,500. As I wrote an earlier version of this essay, the number was 3,000. The death toll in Italy is now over 6,800 and counting.

Regions with excellent healthcare systems are overwhelmed. They send patients who need intensive care elsewhere, even to distant regions, using helicopters. Many die while waiting in line for lung scans. COVID-19 is so infectious that patients, doctors, and nurses are constantly wearing what appear to be spacesuits. When a patient’s condition becomes critical—which on average happens very quickly, within four days from hospitalization—there is practically no way to bring her comfort. While medical personnel scramble around from one emergency to the next, no relative can sit beside her for safety reasons. The way that many must say goodbye to their loved ones is by phone, to the extent that tablets and mobile devices are being offered to hospitals to facilitate such sad communications.

The military is carrying most coffins away on trucks to empty spaces to make room for the ever-steady stream of bodies. You may die quickly and alone, be given almost no funeral, and be carried away from your family.

Alas, misery does not end with dying. Deaths are so frequent that the church bells may toll just once a day, instead of each time a person passes away. No funerals are allowed. Burials rites are limited to essentials. In some areas, funeral companies cannot handle all the business. Coffins have been stored in churches that now are empty, but it is still not enough. The military is carrying most coffins away on trucks to empty spaces to make room for the ever-steady stream of bodies. You may die quickly and alone, be given almost no funeral, and be carried away from your family. Some doctors that are working night and day have rightly said that it is like dying during war.

An Italian flag with the slogan “Andrà tutto bene” (“Everything will be all right”) in Bologna, Italy. Pietro Luca Cassarino / Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

After the Pope encouraged priests to stay close to their flocks and walked through the heart of Rome to pray for Jesus to deliver Italy from the disease, a debate has ensued on the decision to suspend Catholic masses and freeze religious ceremonies. But such debate doesn’t seem to catch the heart of the matter. The fact is that death has come to visit Italian society, culture, and religiosity. Its massive tolls, the brutal way the virus claims lives, and the extra strain the disease has put on managing burials are not merely challenging the Italian way of life, social removal from death and pain, and normal habits of socializing. They are questioning even the processes that we have put in place to fight it. In the areas that are facing the highest fatality rates, ambulance sirens are so frequent that you can’t or don’t feel like singing from the balcony. You certainly don’t clap while your neighbors are mourning their dead or praying for their lives. How can you share #wellbefine? Who is “we,” after all? How can “we” include those who will not survive or will lose their loved ones?

The COVID-19 crisis challenges religious and nonreligious people alike. Everybody was accustomed to life wherein death played a very small role; now everyone is forced to ask what he or she believes in, and whether traditions—whatever they consist of—are instruments of self-deception or adequate responses to an unexpected scenario. These questions can build new social ties as well as increase our awareness of the role of death in our lives and of what is beyond our control. Overall, this crisis can help us grow up.

Time will tell if Italian society, culture, and faith learn the lesson.

Andrea Pin is an Associate Professor of Comparative Public Law, University of Padua, and Senior Fellow of the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University.

Recommended Citation

Pin, Andrea. “An Early Good Friday, at Last: When Too Many Bells Toll in Italy.” Canopy Forum, March 27, 2020. https://canopyforum.org/2020/03/27/an-early-good-friday-at-last-when-too-many-bells-toll-in-italy/