Why Do White Christians in America Think They Are Persecuted?

John Corrigan

Photo by michael_schueller on Pixabay

Over the last decade, the internet has been abuzz with complaints from white American Christians that they are the victims of a broad secularist and leftist persecution. Stung by the decision in Obergefell v. Hodges1 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015)., bewildered by demographic research demonstrating their new minority status, and ever more desperately aligning their Christianity with an indignant populist politics that bemoaned lost greatness, they scanned the cultural horizon for a new way in which to understand their seeming predicament. They soon found it. Reinventing themselves as the North American branch of a vast global Christianity (a process of spatial reorientation in the works for decades), and pointing, correctly, to the severe persecution of Christians in some other parts of the world, they posed themselves as casualties in a nascent war of religion being played out across the globe. All of this took place at a time during which political victories delivered them the Presidency, Senate, House of Representatives, and Supreme Court, as well as a majority of statehouses.

White Christian American belief that the world is a place inhospitable to their gospel is deeply rooted in a foundational Christian theology of suffering and martyrdom. It is, at the same time, an artifact of an American cultural history that only recently has been coming into focus in our rearview mirror. It has much to do with the thorny issue of freedom of religion in the United States. Americans celebrated the First Amendment protections of religion when they became law in 1791, and they have continued to exalt them ever since. Freedom of religion is an admirable ideal, and its enactment in law was an important achievement for the new nation. Since then, however, American history has proven that it is difficult to implement such an ideal. Sectarian intolerance, a constant of American religious history, was always an impediment to religious freedom. Thomas Jefferson, writing to the American playwright and diplomat Mordecai Manuel Noah, lamented “the religious intolerance inherent in every sect.” He observed that “our laws have applied the only antidote to this vice, protecting our religious as they do our civil rights.” But, he said, “more remains to be done, for although we are free by the law, we are not so in practice; public opinion erects itself into an inquisition, and exercises its office with as much fanaticism as fans the flames of an auto-da-fe.” White Protestants, the majority religious group for most of the nation’s history, regularly have launched their own inquisitions into the legitimacy of other American religious groups, always under the pretense that such groups were out to get them.

The historical failure of the Protestant majority to see religious intolerance in America propelled their efforts to see it elsewhere.

The religiously-inspired genocidal campaign against Native Americans — the indigenous heathen devils of the New World — was the proving ground for a praxis of violence that Protestants perpetrated against their rivals. That broader history of Protestant violence against other groups is largely absent from school textbooks because it challenges a story that Americans have fashioned over many generations: the brilliant success of freedom of religion in the United States. Yet, Protestants burned down Catholic churches and convents in New England and elsewhere and periodically went to war with Catholics outrightly. In Philadelphia, in pitched battles with rifles, cannons, and bombs, Protestants razed the greater part of a Catholic neighborhood in 1844 and killed a large number of its inhabitants. Those Bible Wars, alongside the Mormon Wars, the systematic erasure of African spiritual traditions and lives of the slaves who practiced them, the depredations of the Protestant Ku Klux Klan, and a long series of events leading up to the bonfire of black churches in the 1990s, the tragedy at Waco, and recent mass shootings of Jews and Muslims are part of a long and consistent history of religious violence in America. Along the way, Catholics sometimes have joined in when their own self-interests have stood to benefit.

Americans rarely have reflected publicly on the causes or meanings of such incidences of violence. Although in recent years a ratings-obsessed media has shined a brighter light on all things violent, historically, Americans have preferred to forget religious violence. In a maneuver similar to how contemporary Americans seek immediately to chase from memory the trauma of mass shootings by filtering them through a screen of promised “thoughts and prayers,” American Protestants willfully forgot about the religious violence that they perpetrated. They did so by repeatedly boasting about the First Amendment: diversionary, self-congratulatory public celebrations of freedom of religion often took place in the wake of religious violence. They especially practiced sleight of hand that loudly directed attention overseas, where, according to Protestant leaders, there were real problems with religious violence. Protestant missionaries from the early nineteenth century onward sent dispatches reporting the appalling brutality of Asians, Africans, and others against Christians, and begged their supporters at home for help and prayers. Those entreaties were widely circulated and raised large sums of money for the missionary crusade. In the mid-nineteenth century, the State Department, spurred on by the Protestant leadership and press, embarked on a program of identifying offenses against American Protestants in Catholic countries (such as refusing marriage outside of a Catholic ceremony) and attempted to squeeze those nations to sign treaties that protected the religious leanings of American tourists. Over the next hundred years that diplomatic project became a preoccupation of Protestant leaders, who importuned every president from McKinley onwards to take a stand against what they perceived as overseas outrages against their faith. During the Cold War, that project solidified as a battle against godless communists, as evangelicals, especially, demanded that the United States act to protect religious freedom — of Christians — in places where communism had taken root or threatened to spread. As evangelicals grew their political capital in the runup to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, and subsequently as an influential constituency in Washington, they sought more sweeping legislation directed at the persecution of Christians overseas.

In 1996, the National Association of Evangelicals issued its Statement of Conscience, a condemnation of “world-wide religious persecution,” in which it listed as a primary crime “church burnings.” The locations of persecution listed were “many Islamic countries” and nations ruled by “communist regimes” that persecuted persons of “Christian faith.” Issued on January 23, ten days after new fires burned two African American churches in Boligee, Alabama — there were dozens of African American church burnings during this period of time — the document made no mention of the United States among the offenders and no mention of church burnings in America. Islam was the only religion mentioned besides Christianity, and Muslims were cast as persecutors. That statement shortly became the foundation for the International Religious Freedom Act (1998). Much heralded by evangelicals, the IRFA stipulated that the United States was to scour the world for offenses against religion (read: Christians) and to punish those offenses. And, indeed, there were plenty of offenses against Christians, from intimidation to mass murder, to condemn. The IRFA, however, was an angry, vindictive, and rhetorically charged piece of legislation as it developed, brimming with complaints about persecution of Christians in other parts of the world, and self-assured in its determination that an exceptional America, a Christian model for reprobate nations, would beat down the offenders. As such, it epitomized the politics of distraction: how could there be religious intolerance in America when the rest of the world appeared so guilty?

…a large body of Christians positioned themselves to continue to believe that a Christian America was not guilty of intolerance. But, a post-Christian America was.

But the IRFA proved to be a false summit. Crestfallen in the immediate aftermath of Obergefell, evangelical Protestants and some Catholic allies conceded defeat. James Dobson, evangelical leader of the Christian ministry Focus on the Family, lamented, “We lost the culture war,” and the conservative Christian Research Journal announced, “The culture war is over. We (the Christian Right) lost.” Scrambling to make sense of how their God had failed to deliver them the victories that they believed were crucial to their survival as the party of God, they looked overseas. What they saw was a world in which Christians everywhere suffered, a global persecution of Christians. And just as they had exported American intolerance for generations, conceptually displacing religious violence in America to a foreign shore, they now imported it back into America.

This is why white Christians in America believe they are persecuted, why they vent their rage about wedding cakes. The historical failure of the Protestant majority to see religious intolerance in America propelled their efforts to see it elsewhere. They forgot about it by imagining it as an overseas problem. When they finally did see intolerance, it was through a recursive process of having shipped it overseas, and then inviting it back home. In the early twenty-first century, intolerance, in the view of those Christians, still did not exist in America because America had become a foreign country to them, and the persecution of Christians in America was imagined as intrinsically joined to the difficulties experienced by Christians globally. Facing an American future in which Christians would be a shrinking minority, those who had been unable to come to terms with their historical persecution of other Americans remained unable to do so. Characterizing themselves as persecuted, declaring themselves to be victims, but at the same time depicting the nation as having abandoned its Christian foundations, a large body of Christians positioned themselves to continue to believe that a Christian America was not guilty of intolerance. But, a post-Christian America was. ♦

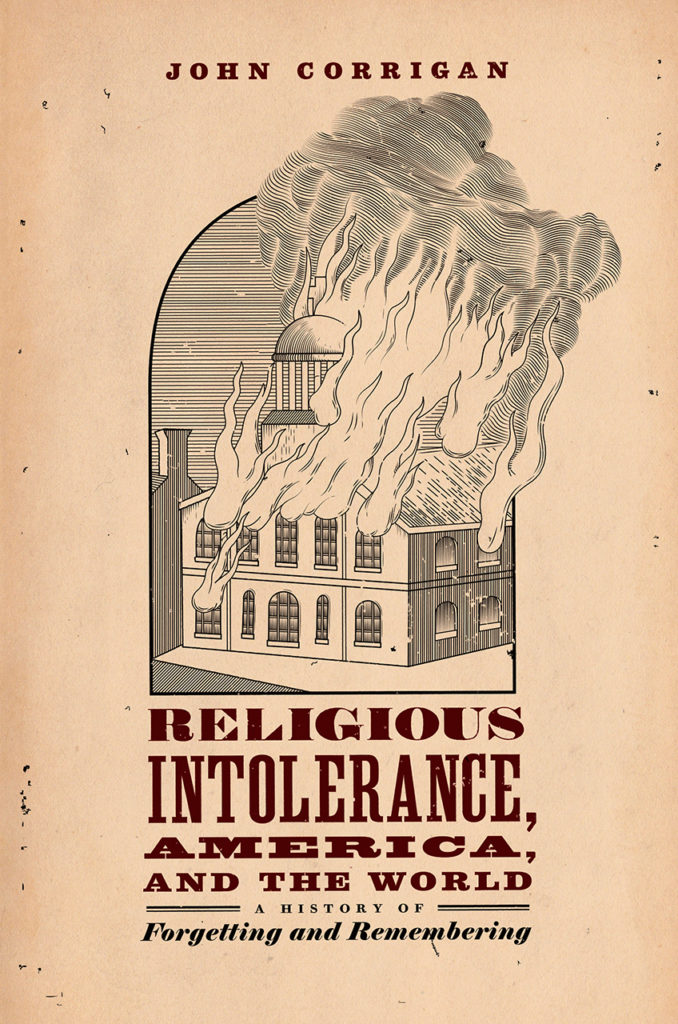

John Corrigan is the Lucius Moody Bristol Distinguished Professor of Religion, Professor of History, and Distinguished Research Professor at Florida State University. His new book is Religious Intolerance, America, and the World: A History of Forgetting and Remembering (University of Chicago Press, 2020).

Recommended Citation

Corrigan, John. “Why Do White Christians in America Think They Are Persecuted?” Canopy Forum, June 23, 2020. https://canopyforum.org/2020/06/23/why-do-white-christians-in-america-think-they-are-persecuted/