Law and Religion in an Age of Rapid Secularization

Frank Lechner

Trinity Church on Broadway and Wall Street, New York City. Photo by TLM1995 (CC BY-SA 4.0).

In the relationship between law and religion, one side is in trouble. Historically, their ties were deep and meaningful. In the recent past, they dealt with many contentious issues, though none caused separation or divorce. The legacy of old commitments continues to shape their current interactions. But recent sociological research, which I briefly summarize in this essay, shows that religion is in marked decline across developed countries, including the United States. That destabilizes the relationship. (For the sake of brevity, I leave issues of definition and methodology entirely aside.)

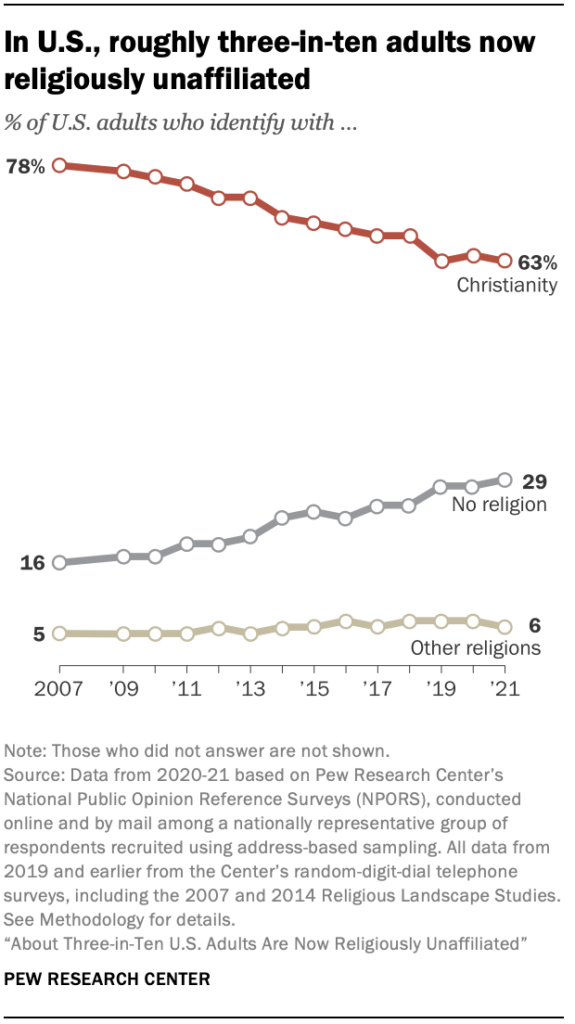

Not long ago, many colleagues in American sociology of religion insisted that it couldn’t happen here — by contrast with Europe, the U.S. retained its religious vitality and organized religion thrived there. Didn’t comparative data show that more Americans believed in God and valued religion? Didn’t churches still have an important role in civic life? But events have shaken their faith in the American religious exception. Of course, mainstream media have amply reported the rise of the “nones,” the growing segment of the religiously unaffiliated, now comprising more than a quarter of the population.

Recent research backs up that coverage. “American religiosity has been declining for decades,” David Voas and Mark Chaves conclude in a 2016 paper, and “each successive cohort is less religious than the preceding one.” Reviewing a wide variety of indicators, Chaves makes an equally clear point in American Religion: Contemporary Trends (2017): “The trend is toward less religion.” Reporting World Values Survey data in his tellingly titled book, Religion’s Sudden Decline (2021), Ronald Inglehart notes a particularly rapid “surge of secularization” in the U.S.: for example, in 1982, 52% of Americans said that God was very important in their lives and only 2 percent that they did not believe in God, but by 2017, those proportions were 23% and 22%, respectively. Since 2000, he says, a composite “religiosity index” has been going down with “increasing steepness.” But it’s not just America. As Detlef Pollack and Gergely Rosta show in Religion and Modernity (2017), and as Inglehart confirms with more recent data, many other countries have witnessed similar declines, as many former adherents leave “without a sound” and new cohorts of young people lose faith decade after decade.

Conventional sociological wisdom suggested many reasons why it wasn’t supposed to happen, but these have not held up well. For example, competition in America’s diverse “market” would stimulate religious vitality, Rodney Stark and colleagues used to claim, and even Europe might enjoy some renewed “churching” as it opened up to more diverse suppliers. That notion always faced some obvious problems — religion seemed to do rather well in homogeneous Utah, and fresh competition in the Netherlands had not slowed secularization there. A 2020 paper by Daniel Olson and colleagues shows conclusively that diversity does not stem decline; in fact, across U.S. counties, higher religious diversity in one period presages larger decreases in participation in later periods. To take another example, Peter Berger had once argued that pluralism weakens the “plausibility” of faith but, impressed with new movements in the global South, he changed his mind to prognosticate coming “desecularization” and declare European decline the “exception.” On this score, the evidence is mixed: some former communist countries, where religion had long been suppressed, and a few others have indeed seen modest revivals, but overall secularization has accelerated, not just in Europe but across higher-income countries. Expectations of widespread desecularization look increasingly unrealistic. A final, more subtle piece of conventional wisdom stressed the different paths countries took in becoming modern, some of which enabled faith and its institutions to preserve their social significance or even raise it in periods of intense conflict — Poland in the era of John Paul II was a case in point. The idea of path dependence still makes good sociological sense, and institutional arrangements still vary, but it does not appear that such variation can shield religion’s role in society over time. For example, Andrew Greeley’s old notion that religion’s role in Catholic communities remains relatively unchanged does not fit recent facts, and converging trends reported by Pollack, Inglehart, and others, suggest that previously distinct paths lead in similar directions — even in Poland.

Why is this happening? From a very long-term perspective, we may be seeing a late stage in modern rationalization or differentiation — take your pick of jargon. An institutional division of labor increasingly sidelines organized religion and faith becomes just one way of viewing the world among others. In a 2020 paper, Jörg Stolz sums up a line of research that adds several “mechanisms” to that old secularization story. Two fit the narrative quite closely: growing secular competition, from entertainment to therapy, and rising levels of education are both associated with lower religiosity. In addition, religious socialization increasingly fails to reproduce faith and allegiance, as parental efforts diminish, children’s resistance rises, and lower religiosity in the wider culture further inhibits transmission. As David Voas has argued, all developed countries experience a “secular transition” when initially small numbers of parents whose fidelity is “fuzzy”, produce more fuzzy or actually secular offspring, who in turn raise even fewer religious children, and so on — a secularizing pattern Simon Brauer calls “self-reinforcing” in a 2018 paper. Inglehart uses the comparative World Values Survey to suggest two other factors: the more people adopt “individual choice” values and the more secure they feel based on income and overall development, the less religious they are likely to become. Of course, security and human development are confounded with lots of other country characteristics, as is religious socialization, and sorting out their relative impact remains a challenge. But the confounding itself conveys a kind of message, in the sense that what we may now be observing in many countries is really a systemic change in which many things link up with many other things — but all with similar religious effects.

[R]eligious socialization increasingly fails to reproduce faith and allegiance, as parental efforts diminish, children’s resistance rises, and lower religiosity in the wider culture further inhibits transmission.

Such generic factors affect the United States as well. But in a 2022 lecture at Emory University, Christian Smith argued that some specific causes boosted the secularizing surge there. The mixed metaphors in his title bluntly make his point: “Converging Perfect Storms: Hard Hits on American Organized Religion Since 1990.” One storm is the change in family life: divorcees, single parents, and unsettled “emerging adults” are less likely to stay religiously involved. In the culture at large, sexual norms increasingly deviate from traditional religious teachings, reducing their appeal. The common sense during the Cold War that religion bolstered cohesion atrophied after 1991, as did the perception that being religious was an inherently good thing, necessary to become a moral person. Some hits, such as denominational conflict, were self-inflicted: in recent decades, religion hardly appeared as a comforting haven in a heartless world. The storms and hits don’t just empty churches or harm “organized religion”: they alter the very landscape of American culture. In previous work, Smith had proposed that we should view secularization not as the unintended outcome of deep social processes, but (also) as the result of deliberate reform efforts and political conflict — progressive elites around 1900 carried out a “secular revolution,” including in the legal domain. I suggest that idea may apply today as well. Challenging the public significance and private plausibility of traditional faith, modern progressives promote new ways to teach sexual ethics or prevent discrimination against sexual minorities, support the negative cultural representation of conservative religious communities, question the status of religiously-identified institutions, advocate spiritual and ideological alternatives to religious traditions, and within various religious groupings try to align their activities with progressive priorities. That second secular revolution is by no means complete and has triggered some resistance, but it frames an ongoing struggle, fought partly in the courts.

Recent rapid secularization in developed countries, including the United States, weakens the institutional presence and cultural impact of religion. That destabilizes the relationship between law and religion, creates new conflicts in it, and calls old commitments into question. Especially in the U.S., disputes over the meaning and scope of various rights, the future of marriage and the family, support for religious education, the merits of traditional morals legislation, the balance between nondiscrimination and religious freedom, and many other such issues, now unfold in a very different context. Ultimately, they have to do not just with resolving this or that conflict in good lawyerly fashion but also, at the risk of sounding a little grandiose, with redefining the place and meaning of religion in modern society.

Students of law and religion have encountered revolutions before. They know the relationship has never been exactly stable and will find parts of the current predicament familiar. My point is not to predict the demise of one partner or complete separation, certainly not on a global scale. I stress common directions, not inevitable outcomes. But if the picture sketched in this essay is correct, the study of law and religion also confronts something new. Though it has properly covered both premodern and nonwestern settings, it has also helped to chart one dimension of the growth of the liberal social order in the West. The formation of that order, anchored in and protected by law, drew on a Christian cultural legacy and could reasonably assume that church and faith remained vital forces. What happens when the legacy is mostly gone and the assumption mostly false? ♦

Frank Lechner is Professor of Sociology at Emory University. His publications include books on globalization and national identity as well as papers on religion and social theory.

Recommended Citation

Lechner, Frank. “Law and Religion in an Age of Rapid Secularization.” Canopy Forum, June 29, 2023. https://canopyforum.org/2023/06/29/law-and-religion-in-an-age-of-rapid-secularization/.