European elections 2024: Successes and failures of far-right political parties

Jeffrey Haynes

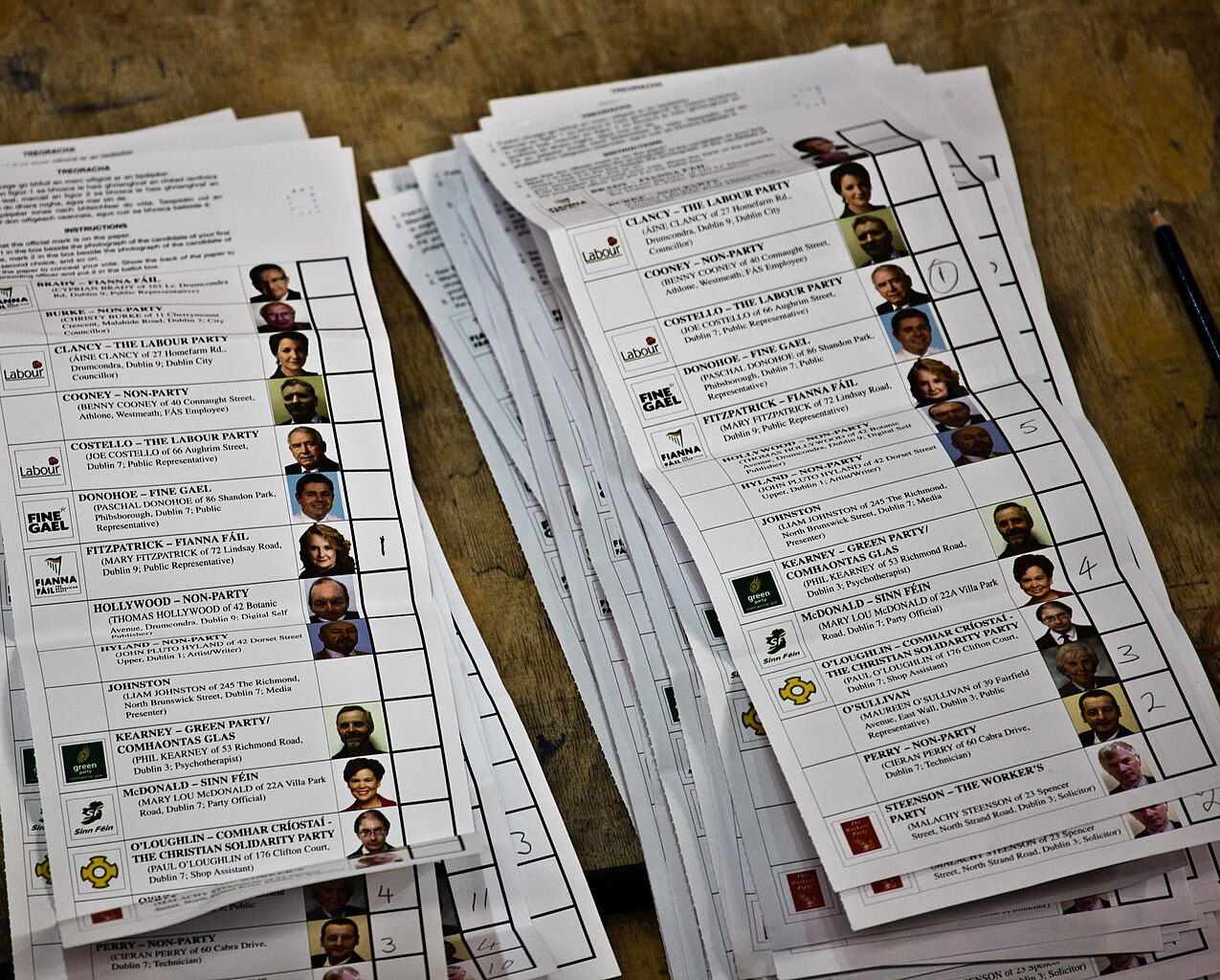

Photo of 2014 Irish Election Ballots by William Murphy (CC BY-SA 2.0)

This article is part of our series on Transnational Christian Nationalism, and its impact on politics, the rule of law, and religious freedom. If you’d like to explore other articles in this series, click here.

The Far-Right in France and Germany

Europe’s right-wing parties had a reasonably good electoral year in 2024. In several regional countries, including regional giants, France and Germany, they managed to get a significant share of the popular vote, typically higher than in prior elections. At the same time, however, none managed to achieve the breakthrough which they all seek: accession to power alone, so as to put into effect policies which they believe are necessary to advance their countries’ political and economic fortunes. In short, the verdict on right-wing parties’ electoral fortunes in 2024’s Europe might be put colloquially: close, but no cigar.

On the other hand, political parties conventionally labelled ‘far-right’, ‘hard-right’ or ‘populist nationalist’ are members of coalition governments in various western European countries, including the Netherlands, Italy and Finland as of September 2024. It is quite difficult to definitively label such parties because they frequently change their name and their precise policies differ somewhat from country to country, reflective of local historical, cultural and political legacies which help mold their policies. And they are not entirely novel in the sense that they may be in or near to power. For example, in 1994 the late Silvio Berlusconi, a right-wing politician and former Italian prime minister, was the first post-World War II European leader to form a government with a far-right party , the post-fascist political group, the Italian Social Movement Movimento Sociale Italiano. In 2000, Austria’s Conservative Party entered a coalition with the far-right Freedom Party. The European Union’s (EU) response was to forbid official bilateral contracts for several months with Austria. The EU’s action in relation to Austria a quarter of a century ago underlines how for many decades it was a post-World War II norm that mainstream – that is, non-extremist – parties in Europe would not countenance doing political deals with the extreme right in order to get into power. Today, things have to some extent changed – but not to the extent that far-right wing parties have been catapulted into power via the ballot box in Europe.

France recently came close to this outcome. On July 7, 2024, the country woke up to face what to many seemed as an unwelcome and daunting scenario: France could be ruled by a ‘far-right’ party, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (Rassemblement National; RN), following a second round of parliamentary elections scheduled for later that month. Not only was France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, highly concerned by this scenario, so too was the European Union in Brussels, as well as governments across Europe. Did the result of France’s parliamentary elections mean that France, historically the country of ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’, would be the first major European country in recent times to elect to power a party whose ability to play by the rules of democracy was by no means assured?

Despite the remarkable showing by the RN in the first round of voting in early July, the party failed to achieve a majority in the legislature following the second round of voting. French centrist and leftist parties strategically withdrew candidates to bolster each other’s contenders ahead of the decisive second round. The result was that the RN, which was widely expected to take power after the second round of voting, was beaten into third place. A hastily constructed, left-wing alliance, the New Popular Front (Nouveau Front populaire) won most seats. France faced a hung parliament with no party having anything like a majority. The RN’s leader, Jordan Bardella, sulked following the resounding defeat, blaming what he referred to as ‘unnatural political alliances’ for stopping the RN in its tracks.

A few weeks later, in August 2024, Germany’s media was filled with similar concerns that France had previously exhibited . The far-right party, Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, AfD;), was expected to make major gains in state elections, including in the eastern states of Thuringia and Saxony. These would have been the first wins in the region (Thuringia) for the extreme right since 1945 when the Nazis first entered regional power in 1929 and on the date when Adolf Hitler invaded Poland in 1939.

The AfD’s campaign slogan in Thuringia was ‘The East will do it!’ Like that of the RN in France, the AfD campaign raised the usual right-populist themes. There was also a specific regional and national focus. The AfD suggested that the country’s east was where the ‘real’ Germany was located; the part of the country holding out against the liberal intrusions of ‘multiculturalism’ and ‘wind power’. One commentator noted that there is ‘only one way to keep Germany’s far-right AfD at bay. Address the concerns it exploits’ with ‘constructive debate on sensitive issues’.

But not all is what it seems in relation to the AfD’s electoral success in Thuringia. During Thuringia’s 2019 election,, the AfD won 23.4% of the votes. In 2024, it won 32.8%. This seems like a big jump in support, but it requires context. . Between 2019-2024, the following happened: the Covid-19 pandemic from 2020-2023, Russia’s war in Ukraine beginning in February 2022, and the resulting energy crisis caused by Germany’s significant dependence on Russia’s gas. Add to this a country led by an awkward coalition under an unpopular chancellor whose party, the Social Democratic Party of Germany, got less than 26% of the votes in elections in 2021, and who is widely believed to be rather tentative and hesitant. Put another way, the 2019-2024 period was an ideal context for anti-establishment right-wing populism and conspiracy theories. Yet, after this traumatic period, the AfD has managed to convince fewer than 10% additional voters, in its strongest state, to back the party at the ballot box.

Europe and Democracy: The Story So Far

Europe has both right-wing and far-right political parties. The latter include ‘persons or groups who hold extreme nationalist, xenophobic, homophobic, racist, religious fundamentalist, or other reactionary views’ (The Encyclopedia of Politics). Right-wing parties, on the other hand, are characterised not by extremism but by an emphasis on ‘notions such as authority, hierarchy, order, duty, tradition, reaction and nationalism’. In Germany, the Christian Democratic Union (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands) falls into this category, while in France, The Republicans (Les Républicains), is a liberal conservative political party, largely inspired by the tradition of Gaullism. We have already noted far-right parties in France and Germany, the RN and the AfD, respectively.

Europe’s right-wing and far-right parties must work within the frameworks of the region’s democratic systems. That is, like other political parties, they are necessarily bound by the conventions, rules and values of democracy and must work within that context to try to achieve power. It is not going too far to say that to be European is to be democratic. For example, membership of the EU, an economic and political union of 27 regional countries, is premised on member states being functioning democracies. Any country which does not have regular, free and fair elections would not be admitted to membership to the EU.

It is claimed that some elements of the AfD are not democratically-orientated. This is a key reason why the party is so feared, not only among mainstream opinion in Germany but also generally within European countries and the EU. The AfD is accused by centrist politicians in Germany of plotting to take power by force, if necessary, in a manner reminiscent of the Nazis rise to power in the 1930s.

It is very difficult for far-right parties in Europe to achieve power by the ballot box in free and fair elections. This is because the political appeal of far-right parties is necessarily limited to the relatively small percentage of voters who agree with their views, values and beliefs and care enough to actually vote for them. In Germany, as in France and elsewhere in Europe, this remains a relatively small proportion of voters.

Europe’s far-right political parties represent a strand of populist nationalism which informs their political ideology and combines ultra-nationalism with populist rhetoric and themes. Rhetorically, this typically comprises anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the perceived Establishment (more specifically, the ‘powers that be’, the state and the parties habitually included in government, the CDU, SPD and Greensto the ‘powers that be’, the state and the parties habitually included in government, the CDU, SPD and Greens) and claims of speaking to and for the ‘common people’, and exhibiting a pronounced dislike of ‘foreigners’.

Far-right populist nationalist parties in Europe typically identify their main ‘enemy’ as Islamist extremism, radicalism, and terrorism. Islam is vilified as a faith and Muslims are regarded with suspicion. Ole Waever, a professor and scholar of international relations, notes that it is fashionable to ‘talk of a ‘clash of civilizations’ between the West and Islam’. Such talk has its origins in the events of September 11, 2001 (‘9/11’), whose outcome is a continuing concern for the West’s social and political stability, leading to widespread ‘securitisation of Islam’. Waever claims that the world may be ‘standing on the brink of a long conflict, perhaps a new “cold war” that features small-scale, but spectacular violence’. Concern with escalating intercivilisational conflict between the West and the ‘Muslim world’ is unquestioningly one of the key reasons for significant electoral support for far-right parties, such as the AfD and RN.

Europe’s far-right parties pitch their electoral appeals to voters by engaging in the politics of culture wars. Culture wars have emerged as an election issue in a region likeEurope, which was long thought to be relatively immune to these political issues. Having undergone both the devastating impact of the rise of far-right political ideologies in the 1930s and determined attempts by the Soviet Union post-World War II to spread its communist ideology, Europe, at least in its Western portion, was judged to be a place where democracy was so highly valued that extremist ideologies would have no real chance ever again to succeed electorally.

Today, however, many urban areas across Europe contain areas of pronounced social deprivation, often the home both to recent migrants and to ‘working class’ white voters. Extensive immigration to Europe, especially the western part of the region, coupled with enhanced regional mobility of people due to the geographical expansion of the European Union, has resulted in increasingly multicultural societies. Recent political developments, such as the recent rise of the United Kingdom’s Reform Party, highlight that many, perhaps most, Europeans tolerate – rather than actively embrace and welcome – integration and immigration. This is particularly apparent in times of economic stress, such as the time of this publication (late-2024), when many people take comfort in older forms of identity, including references to cultural models of Christianity, believing that they exemplify and underline two key components underpinning modern European culture: liberal and individualistic values. For some, this sets apart European culture from what is seen as different – that is, less liberal, more conservative – values and norms of Europe’s Muslim immigrants, many of whom hail originally from the Middle East and North Africa, as well as South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

While Europe’s far-right political parties are not ideologically identical, they do share significant characteristics. First, they are strongly influenced by nationally specific factors such as political history, system and culture. Second, they tend to work from a similar ideological ‘playbook’. Third, as populist parties, it is not surprising that their main political target is an allegedly corrupt incumbent elite political class, from which the mass of the ordinary people needs defending, and for which the right-wing populist nationalist politician claims to be the saviour. Fourth, Europe’s far-right political parties claim to champion the rights and legitimacy of the indigenous, culturally similar, ‘ordinary people’ against the ‘immigrant-loving’, self-serving business ‘elites’ who, they declare, want mass immigration for self-interested economic reasons: to flood the jobs market with ‘foreigners’ willing to work for comparatively low wages and undercut indigenous workers’ salaries for bosses’ profit. The US political scientist, the late Samuel Huntington, claimed that ‘these transnationals have little need for national loyalty, view national boundaries as obstacles that thankfully are vanishing, and see national governments as residues from the past whose only function now is to facilitate the elite’s global operations.

‘Can immigrants and foreigners – that is, the Other – be trusted?’, is a common theme of today’s far-right populist nationalists. Some, such as Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, refer to ‘the’ people in a specific way and with a certain understanding of what the term implies: they do not mean all their country’s citizens. Orbán is referring to ‘our’ – that is, indigenous Hungarian – people: white-skinned, Catholic Christians, not Muslims. Raffaele Marchetti, a political scientist and professor of international relations, refers to such linking of culture and religion with nationalism as ‘civilizationism’. He explains that ‘the civilizational model is centred on the primacy of the cultural and religious bond [. . .] Within the political and economic context of globalization, characterized by a high degree of political and economic exclusion, the perspective of civilizations offers grounds for a conservative rejection of global transformations’ and that ‘Key factors contributing to conflict principally relate to the fact of irreducible cultural differences’.

What Does Europe’s Far-Right Want?

What principally animates right-wing populist nationalists is the political, social, and economic impact of supposedly ‘irreducible cultural differences’, a common component of culture wars not only in Europe but also in the USA. Typically, Muslim immigrants are regarded as the ‘Other’, and function as the main political and ideological target of far-right parties… It is not, however, especially important whether they really are ‘irreducible cultural differences’. The key issue is a political consideration: can the far-right, populist, nationalist politician persuade a sufficient number of voters that such differences exist and that they are so important that voters will cast their ballots for them? Buzan and Waever note that ‘limited collectivities (states, nations and, as anticipated by Huntington, civilisations) engage in self-reinforcing rivalries with other limited collectivities and [. . .] such interaction strengthens their we-feeling’. Because this ‘involves a reference to a “we”, it is a social construct operative in the interaction among people. A main criteria (sic) of this type of referent is that it forms an interpretative community: that it is the context in which principles of legitimacy and valuation circulate and within which the individual constructs an interpretation of events’ (Buzan and Waever 2009, 255). In other words, vote for me and I’ll save you from the bad guys. Who are the bad guys? Anyone sufficiently different from ‘us’ to warrant the term and thus attract our suspicion.

Explaining the political successes and failures of Europe’s far-right political parties does not depend solely on what happens within the region. Marchetti points to multifaceted ‘global transformations’, involving momentous political, social, economic, and technological changes, which have significantly affected Europe, as elsewhere in the world, over the last few decades. An important manifestation of these global transformations is an increasing focus on identity, involving religious and cultural – that is, ‘civilisational’ – configurations. In the early 1990s, political globalisation focused on how to bring about widespread liberal democracy and improved human rights. Today, there are widespread attempts to derail liberal democracy by the far-right. In some European countries, including Hungary, there is significant democratic backsliding involving – among other things– pervasive attacks on human rights and other liberal dimensions of democracy.

The far-right in Europe seeks to exploit these issues and, in some countries, such as Germany and France, is reaping the benefits via an increased share of the vote as a result of some voters’ apathy, despair or anger at the way things appear to be turning out in their country. Far-right populist nationalists are currently riding the crest of the wave of these developments, and many are benefitting electorally. According to sociologist Rogers Brubaker, they seek to benefit from ‘two sets of decades-spanning structural trends’, involving four ‘transformations’: ‘party politics, social structure, media, and governance structures’. They promote ‘a generic populism – a heightened tendency to address “the people” directly – and the demographic, economic, and cultural transformations that have encouraged more specific forms of protectionist populism’. These changes interact with a ‘conjunctural coming-together of a series of [security] crises’: ‘the security crisis’, consequential to a succession of terror attacks by Islamist extremists since 9/11, ‘the Great Recession and sovereign debt crisis’ of 2008, and Europe’s 2015 ‘refugee crisis’, stemming from Syria’s tragic civil war. They occurred ‘in the context of a crisis of public knowledge – to form a “perfect storm” that was powerfully conducive to populist claims to protect the people against threats to their economic, cultural, and physical security’.

This is the backdrop for the current political and ideological efflorescence of far-right populist nationalist parties in Europe which, like their counterparts in the USA with Donald Trump and today’s Republican party, draw on culture-wars issues in the hope of political power. Unlike in USA, however, where Christian beliefs are widely linked to ‘American’ cultural values, many Europeans do not clearly differentiate their traditional ‘Christian’ cultures from those of immigrants, especially Muslims, who, the far-right claims, have very different cultures and values. The far-right in Europe likes to claim that an increased Muslim presence in Europe has resulted in increased societal insecurity. European far-right parties have sought to exploit such concerns, employing an explicit culture-wars approach reflecting one of two broad perspectives.

First, there is a ‘traditional’, patriarchal vision of society focused on a conservative interpretation of Christianity. Such ‘traditional’ Christian values represent socially and politically conservative ideas regarding gender issues, sexual morality, and personal rights. Examples include Marine Le Pen, leader of France’s Rassemblement National, who expresses support for conservative, not overtly Christian, ‘family values’. Second, Dutch right-wing populists, including the assassinated Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn, and his ideological successor, Geert Wilders, leader of the Freedom Party in the Netherlands, are at the forefront of a far-right attack on what they claim is Islam’s illiberalism. This is augmented by ‘philosemitism, gender equality, and support for gay rights’, regarded by the far-right as ‘common European values’, originally derived, they claim, from Christianity, including respect for human dignity and human rights, freedom, democracy, equality, and the rule of law. These far-right populists express ‘putatively liberal views on issues of gender and sexuality as a way of distinguishing’ their ‘Christian civilisation’ from ‘allegedly regressive and repressive Islamic cultures’.

Conclusion

Political scientist Eric Kaufmann notes that all western societies, including those of Europe, are enmeshed in growing, not declining, culture wars. Kaufmann characterises this conflict as between what he calls cultural socialism and cultural liberalism. ‘Cultural liberalism’ is defined by Kaufmann as ‘the belief that individuals and groups should have the freedom to express themselves, should not be compelled to endorse beliefs that they oppose, and should be treated equally by social norms and the law’. Kaufmann defines ‘cultural socialism’ in the notion ‘that public policy should be used to redistribute wealth, power, and self-esteem from the privileged groups in society to disadvantaged groups, especially racial and sexual minorities, and women’. This is said to excuse limitations on advantaged groups in relation to their freedom and equal treatment.

Europe’s far-right political parties would endorse Kaufmann’s notion of cultural liberalism. Parties such as the AfD and the RN would agree that individuals and groups should have the freedom to express themselves, should not be compelled to endorse beliefs that they oppose, and should be treated equally by social norms and the law’.

Results from recent elections in both France and Germany and also from the 2024 European Parliament elections confirm that European countries are undergoing a surge in support for far-right parties. However, while many countries saw significant increases in the votes for such parties, overall this did not amount to an electoral revolution, as the shifts in support varied from country to country.

To put things in perspective, European Parliament elections in 2019 led to far-right parties achieving 165 elected members, little more than 20% of the total. In 2024, far-right parties won around 170 of the 720 seats in Parliament, or 24% of the seats. Thus, like the AfD in Thuringia, the 2019-2024 period, replete as it was with upheaval, trauma and instability, did not translate into a surge for the far-right in Europe more generally.

This is not to suggest that the threat of far-right wins in Europe is a minor concern. But it is to suggest that Europe’s voters are mostly too canny to be persuaded by far-right arguments regarding the problems their countries face. This is also not to imply that Europe’s rulers can be complacent and assume that the far-right threat is not a serious one. How to make it increasingly unlikely that the far-right can ever achieve power generally in Europe should be the main concern of the region’s mainstream political elite. Whether they are up to the task, only time will tell. ♦

Jeffrey Haynes is an Emeritus Professor of Politics at London Metropolitan University, UK. He is the author or editor of more than 60 books and 125 peer-reviewed journal articles (tsjhayn1@londonmet.ac.uk).

Recommended Citation

Haynes, Jeffrey. “European Elections 2024: Successes and Failures of Far-Right Political Parties.” Canopy Forum, October 3, 2024. https://canopyforum.org/2024/10/03/european-elections-2024-successes-and-failures-of-far-right-political-parties/.

Recent Posts