Pakistan’s Hybrid Legal System: Negotiated Coexistence of Secular and Islamic Law

Jo D. Chitlik and Rashid Mehmood

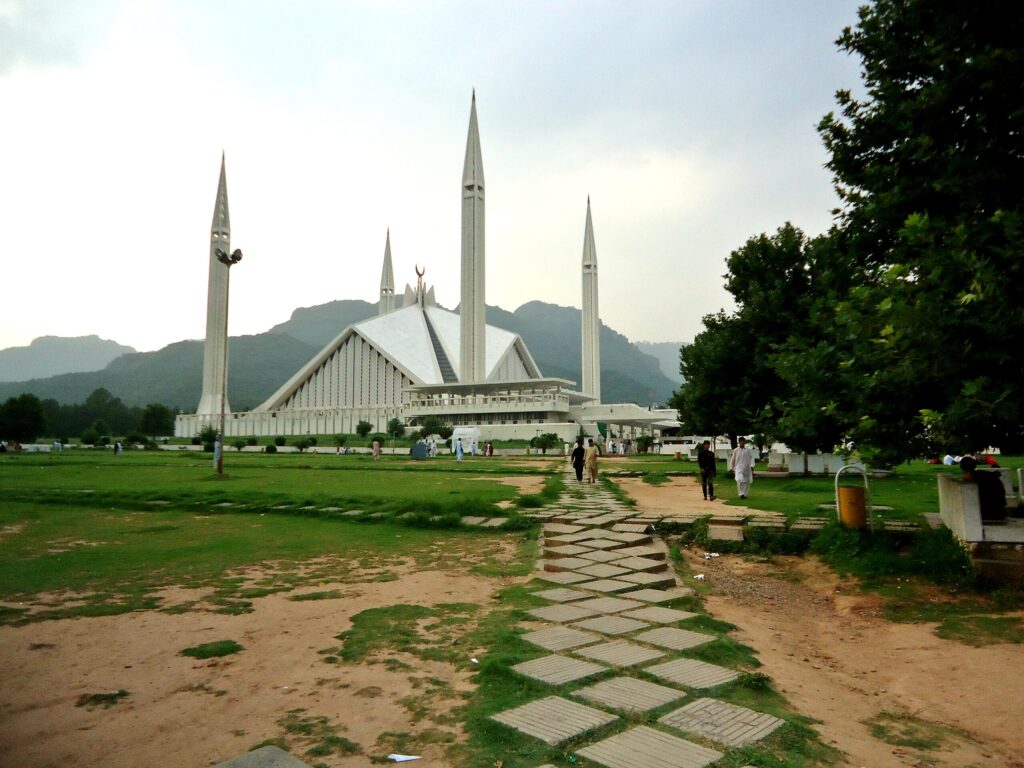

Shah Faisal Mosque, Islamabad, Pakistan via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan’s legal system presents a distinctive pluralistic model, intertwining secular common law inherited from British colonial rule with Islamic jurisprudence, or fiqh, under a single constitutional framework. The 1973 Constitution declares Islam as the state religion and mandates that all laws conform to Islamic injunctions while also safeguarding fundamental rights. This article traces the historical evolution of this hybrid framework, examining the institutional mechanisms through which Pakistan reconciles the competing demands of secular and Islamic law, with particular focus on the judiciary, the Federal Shariat Court (FSC), the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII), and the Shariat Appellate Bench (SAB). The analysis below highlights processes of constitutional negotiation, political compromise, and judicial interpretation. It, then, considers the impact of these processes on Pakistan’s legal identity, particularly in fundamental rights, criminal law, family law, and economic governance.

Colonial Legacy and Early Legal Structures

At the time of independence in 1947, Pakistan inherited the legal system of British India, which was primarily secular and codified in statutes such as the Indian Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure, and the Evidence Act. These secular laws initially formed the backbone of Pakistan’s legal system and were designed to govern a diverse population that did not prioritize Islamic principles, thus reflecting colonial emphasis on uniformity, administrative control, and procedural efficiency. Nevertheless, personal laws governing marriage, inheritance, and family disputes had accommodated Muslim and Hindu customs, providing an early template for legal pluralism. This dual inheritance created a structural tension: the state was tasked with preserving colonial-era secular codes while simultaneously establishing a distinct Islamic identity in law and governance.

The creation of Pakistan was marked by an inherent tension between the preservation of Islamic identity and civic liberalism, a duality reflected in both political rhetoric and constitutional development. The state was founded on the Two-Nation Theory, which positioned Muslims as a distinct political community entitled to sovereignty. However, the Indian politician who successfully campaigned for Pakistan’s independence, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had a vision for governance that suggested a broader commitment to religious freedom and secular principles. In his address to the Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947, Jinnah stated, “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the business of the State.”

This declaration is often cited as evidence of a secular orientation, envisioning a polity in which religion remained primarily a personal matter. Yet, the very foundation of Pakistan as a homeland for Muslims introduced a structural tension between liberal civic principles and the assertion of a Muslim national identity. Jinnah’s broad pronouncements left critical constitutional questions unresolved, setting the stage for subsequent negotiations between secular and Islamic legal principles.

The Objectives Resolution of 1949, adopted by the Constituent Assembly, laid the foundation for the integration of Islamic principles into the legal framework. It declares that the sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to Allah alone, and the authority, which He has delegated to Pakistan, is a sacred trust to enable Muslims to live accordingly. This resolution laid the constitutional foundation for embedding Islam into the legal system while preserving the secular structures inherited from colonial administration. Scholars such as Ayesha Jalal have argued that the Objectives Resolution allowed Pakistan to reconcile Muslim identity with minority protections, whereas Ishtiaq Ahmed contends that it embedded an Islamic identity inseparable from statehood. In practice, the resolution introduced constitutional ambiguity, creating space for negotiation between secular law and religious norms.

Islamization of Law: The Penal Code, Procedural Reforms, and Evidence

The Pakistan Penal Code, initially a colonial inheritance, gradually incorporated Islamic principles–most notably through the Hudood Ordinances of 1979, which introduced Islamic punishments for theft (Hadd al-Sariqa), adultery (Hadd al-Zina), and alcohol consumption (Hadd al-Shurb). These laws exemplified a shift from colonial secularism toward a religiously oriented criminal justice framework. The Code of Criminal Procedure largely retained its colonial procedural structures while accommodating Islamic procedural norms, particularly in cases involving Hudood offenses. Similarly, the Qanun-e-Shahadat Order of 1984 (Pakistani Law of Evidence) replaced the colonial Evidence Act, blending Islamic evidentiary principles with modern legal methodology. For example, the controversial requirement that two female witnesses could replace one male witness in specific cases reflected a literal interpretation of Islamic law, leading to debates about gender equity and evidentiary sufficiency. These reforms exemplify Pakistan’s hybrid legal system, where secular legal structures are maintained alongside Islamic norms, resulting in a carefully negotiated form of pluralism.

The 1956 Constitution marked Pakistan’s first formal declaration as an Islamic Republic. It incorporated the 1949 Objectives Resolution and prohibited laws repugnant to the Qur’an and Sunnah, while simultaneously affirming fundamental rights. Despite these provisions, the Constitution lacked detailed mechanisms for operationalizing Islamic law, leaving substantial discretion to judicial interpretation. The 1962 Constitution, promulgated under President Ayub Khan, initially omitted the Islamic Republic label which generated controversy. However, subsequent amendments reinstated the designation, further highlighting the persistent tension between secular governance aspirations and Islamic identity.

The 1973 Constitution formalized Pakistan’s hybrid legal identity: Islam is the state religion, the head of state must be Muslim, and all laws must conform to Qur’anic and Sunnah injunctions. Simultaneously, Pakistan functions as a federal parliamentary democracy and safeguards fundamental rights, including equality, freedom of expression, and minority protections. Article 227 mandates that all laws conform to Islamic injunctions but exempts personal laws for non-Muslims, thereby operationalizing a balance between secular and Islamic legal principles. To enforce Article 227, the Constitution establishes the Federal Shariat Court (FSC), which is empowered to review laws for Islamic conformity, and the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII), which provides advisory guidance. The Shariat Appellate Bench (SAB) of the Supreme Court reviews FSC decisions, ensuring appellate oversight and harmonization with constitutional norms.

Institutional Mechanisms of Hybridity

Hybridity in Pakistan’s legal system reflects the ongoing negotiation between Islamic jurisprudence and constitutional law. Institutions like the Federal Shariat Court (FSC), Council of Islamic Ideology (CII), and Shariat Appellate Bench (SAB) embody this balance, mediating between divine injunctions and democratic governance. Through review, advice, and appellate oversight, they sustain both Islamic authenticity and constitutional integrity, illustrating hybridity as a force that preserves tradition while adapting to modern legal realities.

Federal Shariat Court (FSC). Established in 1980, the FSC examines whether Pakistan’s laws conform with Islamic injunctions and can review statutes and judicial decisions, striking down laws inconsistent with Islam while prompting legislative amendments. The FSC is empowered to issue binding rulings, yet its decisions often require Parliament to recalibrate legislation to maintain both constitutional legitimacy and Islamic conformity. Significant cases illustrate the FSC’s influence, for example in Haider Hussain and others v. Government of Pakistan where Article 16 of the 1984 Qanun-e-Shahadat Order(Law of Evidence) was declared repugnant to the Injunctions of Islam to the extent that it provided that the testimony of an accomplice is sufficient to carry the weight of a conviction in offences punishable with Qisas, (concept of retributive justice) even if uncorroborated. This would make the conviction illegal. In Mahmood-ur-Rehman Faisal v. Federation of Pakistan, the FSC addressed the prohibition of riba (interest), prompting legislative reform in banking law. In Ghulam Ali v. Mst. Ghulam Sarwar Naqvi, the Supreme Court emphasized inheritance rights under Islamic law, highlighting the FSC’s role in upholding religious principles. More recently, in Sakeena Bibi v. Secretary Law, Government of Pakistan, the FSC declared Swara, a practice of giving girls in marriage to settle disputes, “un-Islamic” and unconstitutional. Through these cases, the FSC has shaped criminal, civil, and family law, balancing preservation of Islamic norms with continuity of legal structures.

Council of Islamic Ideology (CII.) The CII, established in 1962, advises Parliament on proposed and existing legislation. Its recommendations, though not legally binding, strongly influence legislative drafting through political and other common law considerations. Such constitutional design embeds Islamic oversight through specialized institutions, while potentially safeguarding constitutional supremacy and judicial independence. The CII has guided reforms in financial law, notably advocating the elimination of riba and restructuring banking systems, as well as in family law, reviewing the 1961 Muslim Family Laws Ordinance and offering guidance on marriage, divorce, and inheritance.Controversial positions, such as opposition to domestic violence legislation in 2016, underscore tensions between conservative Islamic interpretation and rights-based reforms. The CII exemplifies the advisory role in shaping laws without subordinating parliamentary sovereignty, sustaining equilibrium in Pakistan’s pluralistic legal framework.

Shariat Appellate Bench (SAB). The SAB, as part of the Pakistani Supreme Court, hears appeals against Federal Shariat Court (FSC) decisions and ensures appellate oversight, harmonizing religious compliance with constitutional norms. The SAB, in M. Aslam Khaki Vs. Syed Muhammad Hashim and et al, upheld FSC rulings declaring riba (loosely translated as “interest”) un-Islamic, mandating phased banking reforms, and has guided legislative and regulatory efforts to align economic policies with Islamic principles. The SAB integrates FSC judgments and CII recommendations, mediating between judicial review, legislative action, and Islamic jurisprudence.

Judicial Mediation and Case Law

Pakistan’s judiciary mediates tensions between secular and Islamic law, effectively balancing constitutional guarantees with religious obligations. A prime example is Hammad v. Federation, where provisions of the 2018 Transgender Act were struck down by Federal Shariat Court as being “against the injunctions of Islam” as they permitted self-perceived gender identity and inheritance rights inconsistent with biological sex. However, in Muhammad Akram Khan v. State, the Supreme Court did not consider Islamic doctrines, but rather elevated provisions of fundamental rights by stating that the notion of ghairat (honor) is contrary to the Pakistani Constitution, and that “so-called honor killing amounts to murder simpliciter”. In Muhammad Abbas v. State, the Court again held that Islam does not permit a murder on account of ghairat, a view reiterated in Muhammad Ali Mahar v. State. In Zaheeruddin v. State, Pakistan’s Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the 1984 Ordinance of XX which criminalized members of the Ahmadiyya community for “posing” as Muslims.

The Court ruled that the ordinance did not violate the constitutional right to freedom of religion, as these rights are subject to law, and the Ahmadis’ “mode of worship” was not a protected practice. Nevertheless, the Pakistan Supreme Court in Tahir Naqash v. State, subsequently reaffirmed the constitutionality of freedom of religion by stating that the Ahmadiyya community, as citizens of Pakistan, were free to practice their religion in their own places of worship, including their homes. The 2018 Asia Bibi case further exemplifies judicial negotiation, where the acquittal of a Christian woman sentenced to death for blasphemy highlighted the judiciary’s role in protecting minority rights while navigating Islamic legal frameworks. These and other cases illustrate how Pakistani courts balance constitutional principles against conservative interpretations of sharia, reinforcing the State’s hybrid legal identity.

Sectoral Impacts of Hybrid Law

The sectoral impacts of hybrid law in Pakistan reveal the intricate interplay between Islamic jurisprudence and constitutional principles across multiple domains of governance. This hybridity has profoundly shaped the country’s legal evolution, embedding religious precepts within modern statutory structures and generating both harmony and tension in the pursuit of justice. Across criminal, family, economic, and rights-related sectors, Islamic and constitutional imperatives continuously negotiate questions of authority, legitimacy, and reform.

Criminal Law. Islamization policies, particularly during General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime (1977–1988), intensified the integration of Islamic principles into criminal law. Hudood Ordinances introduced Islamic punishments while sparking debates over human rights compliance. Subsequent reforms, such as the 2006 Protection of Women Act (Criminal Laws Amendment), attempted to reconcile religious mandates with constitutional guarantees of equality.

Family Law. The Muslim Family Laws Ordinance 1961 regulates marriage, divorce, and inheritance. In Fazal Jan v. Roshan Din, the Pakistani Supreme Court held that the denial of women’s inheritance rights violates both Islamic law and the constitutional guarantee of equality. The Court further observed that, in the specific context of the 1973 Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the term State extends to judicial authorities, including judges, when adjudicating matters concerning the protection of the rights of women and children. In a similar vein, the Court in Farhan Aslam v. Nuzba Shaheen affirmed that women’s inheritance rights are constitutionally protected. While FSC rulings, such as Ghulam Ali v. Mst. Ghulam Sarwar Naqvi, have occasionally struck down provisions inconsistent with Islamic injunctions, ensuring alignment with sharia while balancing individual rights.

Economic Law. Efforts to eliminate riba illustrate the challenges of integrating Islamic economic principles into modern governance. Islamic finance law remains a contested area, judgments such as Aslam Khaki Vs. Muhammad Hashim and Farooq Vs. United Bank Limited which declared all forms of riba (interest) prohibited, directing Pakistan’s financial system to become an interest-free nation by December 2027. Initially, the State Bank of Pakistan and other banks appealed the verdict. However, in 2022, the State Bank of Pakistan & National Bank of Pakistan withdrew their appeals. The decision of FSC sets Pakistan on a trajectory toward an Islamic financial order, but the implementation requires adaptation of a modern Islamic banking system. It represents a case where review based upon Islamic jurisprudence is not merely symbolic but potentially transformative making way for Pakistan’s struggle to reconcile Islamic principle with the global financial demands.

Women’s Rights and Minority Protections. Islamic law provides foundational rights to women, yet socio-cultural interpretations sometimes restrict these rights. Judicial interventions, including rulings on inheritance and prohibitions on harmful traditional practices, not based on Islamic law, which illustrate ongoing efforts to reconcile tradition with constitutional guarantees.

Integrating Islamic Law Frameworks

Pakistan’s hybrid legal model is distinctive but can be better understood in the context of other Muslim-majority countries that have adopted varying approaches to integrating Islamic law within their constitutional and statutory frameworks. The Indonesian legal system is largely based on civil law traditions inherited from the Dutch colonial period and has a strong overlay of Islamic law, primarily in personal status and family matters. The 1974 Marriage Law of Indonesia, and related regulations, recognize Islamic law as the governing norm for Muslims in matters of marriage, divorce, and inheritance, while civil law applies to broader commercial and criminal matters. Unlike Pakistan, Indonesia does not have a constitutional mandate requiring all laws to conform with Islamic injunctions. The duality in Indonesia allows for clear sectoral allocation but limits the scope of Islamization to personal law, which has avoided some of the complex jurisdictional conflicts that Pakistan experiences between the FSC, SAB, and civil courts.

Malaysia, on the other hand, employs a dual court system in which civil courts and Syariah courts operate concurrently, each with jurisdiction over specified matters. The civil courts handle general civil and criminal law, while Syariah courts govern Muslim personal law, including family, inheritance, and certain criminal offenses. This system provides structural separation and reduces the need for courts like the FSC or SAB in Pakistan to review secular statutes for Islamic conformity. However, the Malaysian system is not without challenges; conflicts occasionally arise regarding constitutional rights versus Syariah authority, particularly in custody, apostasy, and religious conversion cases. Malaysia demonstrates that institutional separation of Islamic and secular courts can provide clarity but also introduces jurisdictional friction that requires careful legislative and judicial management.

Turkey represents an extreme contrast, as its current Constitution adopted in 1937 reflects a deliberately secularist model influenced by Mustafa Kemal’s reforms. The 1937 Turkish Constitution embodies the principle of laïcité (secularism), it explicitly separates religion from the state, and Islamic law has no formal role in statutory or judicial systems. Family and personal laws are codified along European civil law lines, and the judicial system does not entertain religious injunctions. While this ensures legal uniformity and reduces religiously motivated legal pluralism, Turkey’s experience also illustrates the limits of secularist reforms in Muslim-majority societies, where cultural and religious identity may persist informally in social practices. Turkey’s model underscores the idea that complete secularization is possible constitutionally but may generate societal tensions if popular norms conflict with statutory law.

Iran’s legal system presents another model, one in which Islamic law is fully codified into the constitutional and statutory framework. Following the 1977-1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran adopted a system where sharia is the principal source of legislation, and the Guardian Council ensures that all parliamentary laws comply with Islamic law. Unlike Pakistan’s negotiated hybrid system, Iran’s judiciary and legislative process operate under strict sharia conformity, leaving limited scope for secular or civil legal frameworks to operate independently. While this ensures alignment with religious norms, it has been criticized for restricting fundamental rights, particularly for women and religious minorities, illustrating the potential costs of a non-pluralist approach to Islamic law.

Comparing these models underscores Pakistan’s distinctiveness: its legal system does not wholly secularize nor fully Islamize, but deliberately embeds mechanisms for negotiation between secular statutes, Islamic injunctions, and constitutional rights. Unlike Indonesia or Malaysia, Pakistan does not confine Islamic law to personal matters; instead, the FSC and SAB can review civil, criminal, and economic laws for Islamic conformity. Unlike Iran, Pakistan preserves parliamentary sovereignty and constitutional guarantees. Unlike Turkey, Pakistan mandates Islam as a guiding legal principle for all legislation. This unique combination of pluralism, judicial review, and advisory mechanisms creates a dynamic system capable of evolving over time, accommodating social, economic, and religious considerations.

Pakistan’s hybrid model also illustrates lessons for the broader Muslim world. First, legal pluralism is feasible when structured institutions mediate between religious and secular authority. Second, judicial review can serve as a corrective mechanism, balancing Islamic conformity with constitutional rights. Third, advisory bodies such as the CII can provide non-binding guidance that shapes legislative policy without undermining democratic processes. These lessons suggest that hybridization, while complex, may be a pragmatic solution for Muslim-majority countries seeking to reconcile religious identity with modern governance.

Conclusion

Pakistan’s legal system exemplifies a carefully negotiated coexistence of secular and Islamic law. From colonial inheritance through constitutional experiments to the establishment of the FSC, CII, and SAB, the country balances Islamic conformity with secular governance. Judicial interpretation, advisory guidance, and legislative recalibration sustain this dynamic equilibrium. The system mediates tensions between divine injunctions and secular authority, tradition and modernity, and Islamic jurisprudence and constitutionalism. By institutionalizing dialogue, review, and reform, Pakistan demonstrates that secular and Islamic law can coexist in a modern constitutional order. Its legal architecture is a living experiment in negotiated coexistence, illuminating both the possibilities and challenges of harmonizing secular and Islamic law in a Muslim-majority state. ♦

Jo Chitlik is a U.S. Department of State Fulbright Specialist, a Senior Fellow at Emory University’s Center for the Study of Law and Religion, and Visiting Scholar at Fatima Jinnah Women’s University (FJWU) in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Through their affiliate GlobalLearningOnline.com, Chitlik and her Emory alumni team created Pakistan’s ADR Pilot Program taught at FJWU.

Rashid Mehmood is a Pakistani legal professional with nearly 25 years of experience spanning from advocacy, judicial service, and legal research. He began as an Advocate before the Subordinate Courts in Punjab in 2001, later qualifying as an Advocate of the High Court in 2004. In 2000, he earned his L.L.B. from Bahauddin Zakariya University and in 2025, an LL.M. in International Commercial Dispute Resolution in the United Kingdom.

Recommended Citation

Chitlik, Jo D. & Mehmood, Rashid. “Pakistan’s Hybrid Legal System: Negotiated Coexistence of Secular and Islamic Law.” Canopy Forum, October 17, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/10/17/pakistans-hybrid-legal-system-negotiated-coexistence-of-secular-and-islamic-law/.

Recent Posts