More, Not Less, Religion May Be a Cure for America’s Political Ills

Shlomo C. Pill

Photo by StockSnap on Pixabay (CCO)

Note: This and other essays in this series were originally delivered as part of the Leadership and Multifaith Program symposium on Law, Religious Identity, and Public Discourse held at Georgia Tech on September 26, 2019.

I agree with much of Judge Dhanidina’s rather dour diagnosis of our current societal ills. We are indeed currently experiencing a crisis of confidence in our democracy and institutions. We are experiencing, perhaps, what Charles Taylor has called “democratic degeneration”—a period in which we are moving away from democracy, engaged popular politics, healthy political institutions, and the rule of law.

We are likewise witnessing increased tensions between religious commitments and secular legal, cultural, and policy norms and values. This is true not only for traditionally minority faith communities—Jews, Muslims, Eastern traditions, and Catholics—who have long experienced tensions between America’s once deeply Protestant “civil religion” and their own ecumenical practices and convictions. It is also true for members of the plurality of American Protestant denominations who once comprised a majority of the American population and are now waking up to the 21st century reality that they no longer field the numbers or influence to shape American law and culture in their religious image as they once did.

I also agree with Judge Dhanidia that we are witnessing less enthusiasm for religious faith in this country, though I may have something different in mind than does the Judge.

Some 70% of Americans still identify as Christian, making the United States home to the largest number of Christians in the world. It is true that recent surveys suggest that the number of religiously unaffiliated Americans is growing, and even American Christians are becoming increasingly disinterested in institutional religion. But in both cases it seems that this is more a symptom of the broader loss of confidence in institutions that is also manifesting in the political realm.

More than a crisis of religious enthusiasm per se, I think we are witnessing a crisis of a particular kind of religious enthusiasm—really an absence of a particular kind of religious enthusiasm. And I think this phenomenon is in some ways tied to our broader political and societal malaise.

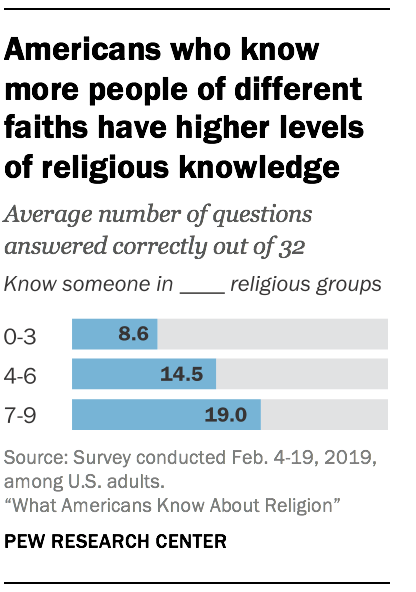

While raw numbers suggest that religion is still an important component of nearly four-fifths of Americans’ identities, I would argue that such religious identity has become increasingly superficial in at least two ways. On the one hand, while many American’s still identify as religious, for many, faith is not a particularly thick aspect of their identity or affiliation. In Jewish circles, we might refer to this phenomenon as “Yom Kippur Jews”; in other traditions, perhaps as “Ramadan Muslims” or “Christmas Christians.” The idea here is that any broad or deep immersion in the teachings, texts, traditions, and complex conversations of many American’s chosen faith is markedly absent. Religious literacy is low.

At the same time, deeper religious commitments seem to trend towards the superficial in another way; among many American religious groups with thicker commitments to religion, those commitments take the form of what Khaled Abu El Fadl has in the case of Islam referred to as Puritanism.1 See Khaled Abu el Fadl, The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam for the Extremists (2005). This is the kind of simplistic faith commitment that mistakenly perceives religion as speaking clearly and univocally; the kind of religious commitment in which old, complex faith traditions are reduced to sound bites—as if religious teachings offer easy, singularly correct answers to every contemporary question. Often, such puritanical religion finds particular expression in the public and political spheres, where it is brought to bear to speak with absolute correctness on a host of hotly debated cultural, legal, and social concerns.

In responding to the theme of Judge Dhanidina’s important essay, I would say that what religion has taught me about law, and what law has taught me about religion is that we ought to be cautious about these kinds of superficial and simplistic religious and legal commitments.

If there is tension between religion and law, the answer is not less religion or less law, but more religion and more law. In other words, there is a need for more religious and legal literacy—for a greater appreciation of the complexity of our religious and legal traditions, and for the substantial indeterminacy of these traditions. There is a need for greater appreciation of the ways that religion and law actually rely on serious commitments from contemporary actors—both elite and ordinary—to use these traditions as foundations for rich normative discourse, and not as fixed blueprints for easy solutions to hard questions.

Here, religious and legal traditions can provide mutually supportive perspectives.

Many religious traditions include deep commitments, not to specific “right answers” to normative questions, but to the importance of searching for answers to such questions; to respectful but firm disagreement, and to the gradual creation or discovery of more and better religious knowledge through active human engagement with religious teachings and traditions. This is true of Judaism, where the Torah admonishes that religious knowledge is not in heaven but is instead “in your mouths and hearts so that you may do it.”2Deuteronomy 30:14. The Talmudic rabbis reinforced this idea by affirming the critical role played by everyone’s own interpretive and constructive engagement with the Torah in determining religious norms. One byproduct of this approach is a strong endorsement of the positive value of normative disagreement: If done right, it is a sign of a healthy religious community and evidence of different people with different perspectives and experiences mining Jewish texts, traditions, and practices in search of meaning and direction.3See Shlomo C. Pill, Leveraging Legal Indeterminacy: The Rule of Law in Jewish Jurisprudence, (2017) The Journal Jurisprudence 221, available at https://www.academia.edu/35469898/Leveraging_Legal_Indeterminacy_The_Rule_of_Law_in_Jewish_Jurisprudence.

Islam, too, includes significant endorsements of the importance of the process of religious searching and engagement—ijtihad—that is not necessarily connected to need to discovering objectively right answers to questions of religious law or practice. In one famous hadith, Muhammad is recorded to have taught that a religious judge that rules correctly after deeply engaging the sources and his own faculties receives two rewards; a judge that rules incorrectly, but who still approached the decision making process with honesty, integrity, knowledge, and proper conviction still receives one reward.4See Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 6919; Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 1716 The judicial automaton—who reaches correct decisions without any need to study, reflect, and interpret—is not even considered. Like Judaism, Islam embraces an ethic of disagreement; the 8th century jurist Abu Hanifa famously said: “I believe my opinions are correct, but am cognizant of the possibility that they may be wrong; I also believe that the opinions of my disputants are wrong, but remain cognizant of the fact that they may be correct.” Such a rich tradition of debate contributes to a religious worldview that is multivocal and complex, and a religious outlook that is humble, interpretive, and searching.5See Shlomo C. Pill, Leveraging Legal Indeterminacy A Judeo-Islamic View of the Indeterminacy Problem and the Rule of Law, 6 Journal of Law, Religion, and State 147 (2018).

Neither law nor religion is well served by superficial or puritan commitments.

What does this have to do with American law? If we have a crisis in politics, law, and civic discourse in this country, it is at least partially due to the fact that we have a serious “right answers” problem. In a rapidly changing and increasingly complex world, many have a deep need for certainty, for simplicity. This is true when it comes to practical policy; and it is even more true when it comes to the values and convictions that underlie policy preferences. Many on both the left and right seek to use the Constitution, the law, morality, and ethics as trump cards to foreclose debate and disagreement. There are right answers —they say— and those who disagree are not merely wrong, but traitorous and illegitimate.

But there is another tradition in American law and thought. What Jack Balkin has referred to as “Skyscraper Constitutionalism.”6 Jack Balkin, Living Orginalism (2011). If you look at our Constitution—and for all its faults it is a brilliant document—the Framers rather consciously avoided making fixed determinations about substantive issues. They created a framework for working through disagreement, not a framework for ending debates.

If religion can teach us something important about law, and law something important about religion, it is that neither law nor religion is well served by superficial or puritan commitments. Healthy and robust religious and political societies require populations committed to—and capable of—real engagement with the indeterminate, multivocal, and still unfolding tapestry of their respective traditions. They require knowledge of the diversity of opinion, the latent possibilities contained in law and scripture, the positive value of robust but ethical and respectful disagreement, and the idea that not every question needs to be settled once and for all.

The stakes are not quite as high as we like to think they are. Religion and law teach humility through commitments to God or to founding charters that are much larger than us. They teach that honest, sincere engagement—not the forceful imposition of that one right answer—is what keeps normative traditions alive and healthy.

Shlomo C. Pill is a Senior Lecturer at Emory Law School and a Senior Fellow at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion. His teaching, research, lecturing and consulting work focuses on church-state issues, as well as religious law in both Judaism and Islam.

Recommended Citation

Pill, Shlomo C. “More, Not Less, Religion May Be a Cure for America’s Political Ills.” Canopy Forum, November 6, 2019. https://canopyforum.org/2019/11/06/more-not-less-religion-may-be-a-cure-for-americas-political-ills-by-shlomo-c-pill/