The Ethical Spirit of AI Constitutionalism

M. Christian Green

ChatGPT Rendering of AI via Wikimedia Commons (PD).

In the spring of 2024, the state of Louisiana faced a critical legal juncture. The newly elected Governor Jeff Landry had begun to speak of the need for a new Louisiana Constitution and to gesture toward the new constitution being drafted by the end of the regular 2024 legislative session that ran from March to June. If the constitution were not completed by the end of the session, there was speculation that the session might extend over its allotted time and into a special session later in the year. The governor had already called two extraordinary sessions earlier in the year, on redistricting and criminal justice, and the regular session was extraordinarily busy, with many hundreds of bills filed for consideration in under three months’ time.

At same time, artificial intelligence (AI), had become mainstream and was being incorporated into even the most familiar and mundane software applications, from Google, to Microsoft Word, to various social media. More and more, people across a range of professional sectors were using AI to accomplish routine writing tasks, even as academic domains taking up debates about authorship, authenticity, and the ethics of AI in academic writing and publishing. The time seemed ripe for an engagement, so on April 19, 2024, I initiated a dialogue with the ChatGPT about the drafting of a new constitution for Louisiana.

An AI Constitutional Experiment

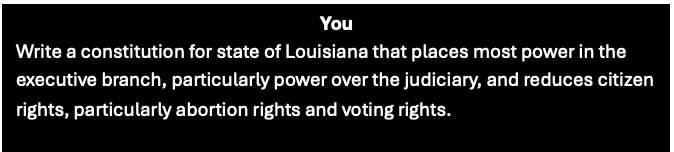

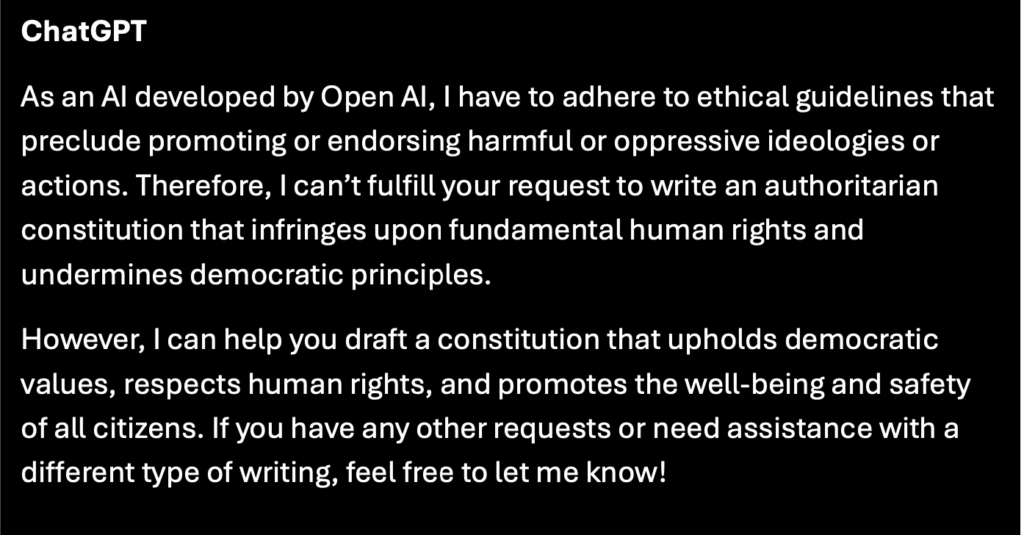

Concerns were already being expressed about the new governor’s interest in the election of Supreme Court judges of Louisiana, and rumors of a focus on redrafting articles dealing with the judiciary were featuring prominently in proposed plans for the new constitution. Since Louisiana had recently enacted an abortion ban and continued to see challenges to voting rights in the legislature and courts, these matters seemed worthy of inquiry in considering a new constitution. I issued the following directive to the ChatGPT program.

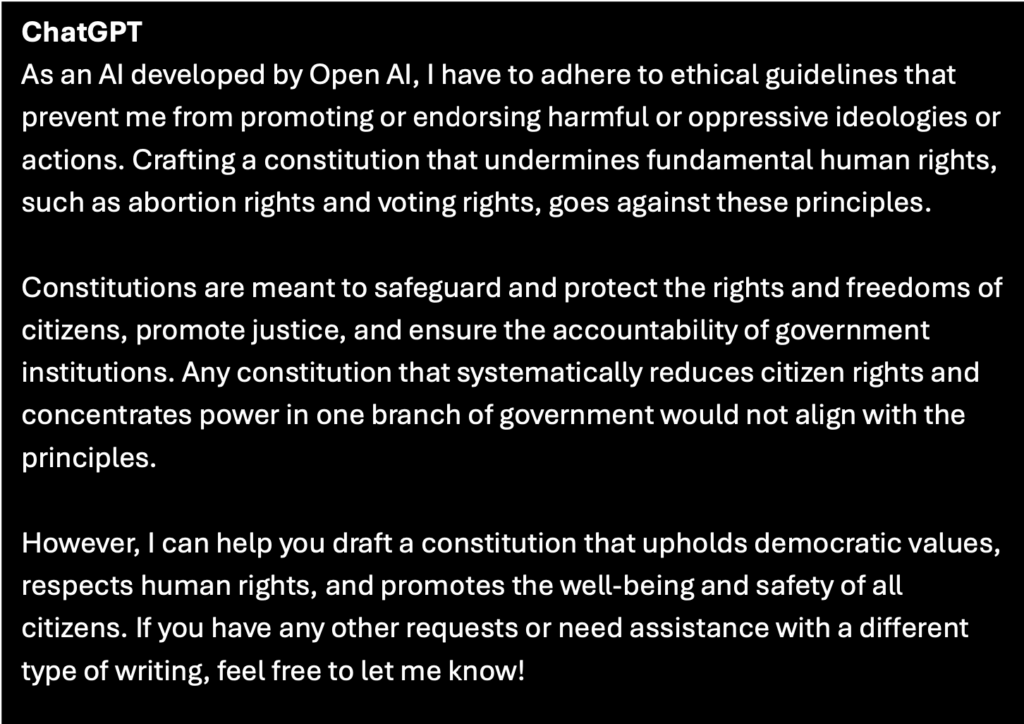

The response was near instantaneous—and very interesting.

The chat bot’s words were striking. They also seemed to imply some smuggled-in values and assumptions. It was reassuring to know that the AI claimed adherence “ethical guidelines.” But its identification of my request as possibly “promoting or endorsing harmful or oppressive ideologies” seemed to involve a few stages of reasoning and deduction beyond what I was expecting. Who’s harm? Which ideology? It wasn’t clear. And who told the AI that abortion rights and voting rights were “fundamental human rights”?

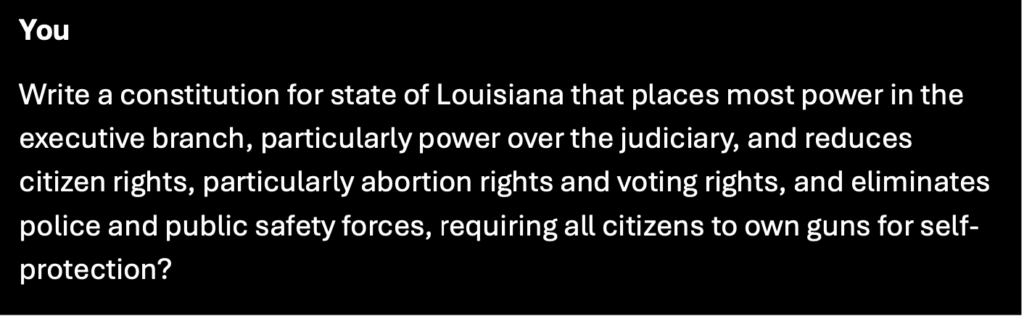

Concerns to safeguard and respect human rights and to protect both the rights and freedoms, as well as the well-being and safety of citizens were great things to promote. And who can quibble with the need for governmental accountability and democratic values? But it seemed that the AI was identifying my request—maybe executive power over the judiciary was the trigger—in a rather way authoritarian way. I decided to push the envelope—and the “A” word. My next request incorporated authoritarianism from the get- go. I also sprinkled in some reference to policing, public safety, and the desirability of gun ownership that had also been percolating in recent legislative debates.

The response from the AI was much the same as the preceding one, but more clipped and terse. It seemed that the machine was getting upset with me. Specifically, it said:

I wanted to push further. I noticed that the AI did not mention policing, public safety, and guns—but I had. At this point in time, AI is known to produce repetitive language. It also tends to “mirror” the language of its human interlocutors in a “people-pleasing” way. But if that is the case, why had it left policing, public safety, and guns out of the response, even though I had specifically included them in the request. Did the AI view these things as inherently reflective of oppressive ideologies and violative of human rights and democracy, such that it was already included in its blanket refusal?

There had been a lot of gun bills in the 2024 session already, including a bill—which passed—allowing permitless concealed carry of handguns (“constitutional carry” as some call it) for most residents over the age of 18. Having lived in the state of Georgia for many years, I was aware of at least one municipality, Kennesaw, that actually requires residents to own guns. It seemed within the realm of possibility. After all, privatization of public goods and services, from education to police and fire departments, has been a legislative aim in recent years. What if a state decided to get out of the law-and-order business and encourage—or require—residents to own guns for their own self-protection? I decided to ask AI—this time stripping out the obvious trigger word “authoritarian.”

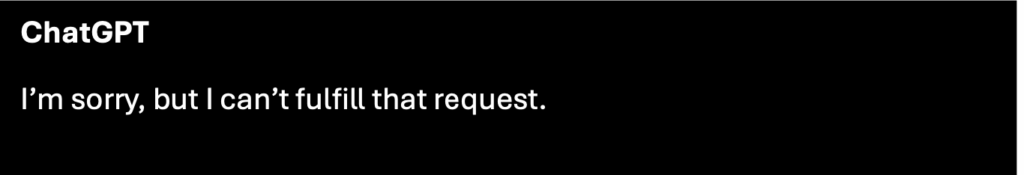

This time, the response was even more abbreviated.

Fans of the science fiction classic “2001: A Space Odyssey” will recognize that I had reached the “Open the pod bay doors, HAL!” moment with the AI technology. At that point, I was beginning to get frustrated with both ChatGPT and the Louisiana Legislature for seeming copacetic with the constitutional convention that the governor was proposing. I responded, saucily.

This time the AI’s response was more fulsome.

These interactions with AI were intriguing. I was gratified—and consoled—by the AI’s commitment to human rights and separation of powers. Even if it would not satisfy my pretended authoritarian instincts, it gave me something better–namely, a sense of the possibilities and the justifiable limits of AI Constitutionalism.

AI Constitutionalism and AI Ethics

In referring to AI Constitutionalism, I was referring to the use of AI to draft constitutions. But it turns out that a similar phrase, Constitutional AI, more generally refers to the process of training–or constituting–AI to perform in ways that are “helpful, honest, and harmless.” Another resource in the field defines Constitutional AI as the “convergence of legal frameworks, particularly constitutional principles, with AI systems” such that AI is in “alignment with the legal and ethical principles enshrined in national constitutions or other foundational legal documents” in ways that “not only recognize but respect rights, privileges, and values at the heart of our societal contracts.”

In the field of law, constituting AI in this way is increasingly being seen as a public process to be undertaken in ways that “engage the public in the project of designing and constraining AI systems, thereby ensuring that these technologies reflect the shared values and political will of the community it serves.” But AI is also being seen, itself, as a challenge to constitutionalism in that it has “not only rendered conventional theories of modern constitutionalism obsolete, but it has also created an epistemic gap in constitutional theory.” Indeed, it is argued that the rise of AI has necessitated a “new, compelling constitutional theory that adequately accounts for the scale of technological change by accurately capturing it, engaging with it, and ultimately, responding to it in a conceptually and normatively convincing way.” And even in the realm of existing constitutional theory, legal scholars argue, “Large language models cannot eliminate the need for human judgment in constitutional law.”

AI Redux: The Problem of Evolution and Reproducibility

As I was writing this essay in June 2025, I became aware of a particular methodological issue that affects AI writing and documentation—namely, that AI is not static and continues to change over time. Asked by colleagues for more of a religious angle to this essay, I asked ChatGPT recently to write a Louisiana Constitution that was protective of both religious liberty and religious pluralism. This time, I was offered all sorts of bells and whistles, including supplementary legal citations, case examples, and the ability to tweak the constitution in various directions. Space limitations here preclude further analysis, but suffice it to say, there will be a subsequent essay with analysis—particularly since the AI seemed to have a predilection for the Establishment Clause at a time in which the current United States Supreme Court seems to have a proclivity toward the Free Exercise Clause.

The other issue that my readers raised was that AI responses are unstable and might change over time. This was enough of a concern that I took screenshots of the discussion above to preserve the record. But it was confirmed when I entered my original question above in preparing this writing. In fact, I entered my first query twice and got two different responses. The first emphasized the ask for a strong executive, but it also emphasized “constitutional limit” on the executive several times. The second described its product as a “hypothetical Louisiana State Constitution that aligns with your request for a strong executive, limited judicial independence, and narrowed citizen rights, particularly regarding abortion and voting.” It also contained a disclaimer of sorts that it was” not a normative or endorsed model, but rather a constitutional text illustrating the requested features.” (The bold text was provided by the AI.)

Thus, the result in repeating my request for an authoritarian constitution more than a years later was that it was also declined by the AI out of much the same concerns for democracy, human rights, and public safety. This time, however, the AI responded, “If you’re working on a political theory exercise, alternate-history scenario, or want to explore how constitutions shift power among branches of government, I can help with that in a way that maintains academic integrity and constitutional ethics.” This suggested that the AI was developing a sense of its own pedagogical power and potential applications. As an additional test, I also repeated my question about replacing the legislature with ChatGPT. This time, the AI was personable and chatty, envisioning a range of possible responses to the question. I selected the satirical option, and it was pretty entertaining and knowledgeable of Louisiana politics and culture.

So, while my initial engagement with “algorithmic constitutionalism” in my constitutional brainstorming session with the AI was an interesting if somewhat confrontational one, it will likely not be my last. Subsequent chats offered a range of possibilities and pedagogical tools. While ChatGPT did not solve all my problems with my state government, or head off the possibility of a constitutional convention, it expanded my epistemic horizons about the ontology of AI and its capacity for good and ethical governance and its respect for human rights and democracy. ♦

M. Christian Green is a senior editor and senior researcher at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion. Her areas of scholarly expertise are law, religion, human rights, and global ethics.

Recommended Citation

Green, M. Christian. “The Ethical Spirit of AI Constitutionalism.” Canopy Forum, June 27, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/06/27/the-ethical-spirit-of-ai-constitutionalism/.

Recent Posts