Sanctuary as Insular Constitutionalism

Bryan Ellrod

FAN Members hold vigil during the Supreme Court hearing by Ilovestfrancis (CC BY-SA 3.0)

This article is part of our series on Law, Religion, and Immigration. If you’d like to explore other articles in this series, click here.

Nomos, Narrative, and the “Alien”

Law is more than a system of codified rules. A world of law, as Robert Cover puts it, is a “system of tension” that at once interposes and bridges the space between our present reality and our visions of possible futures. It is one of the languages by which we narrate the “unredeemed character of reality as we know it” and the “fundamentally different reality that should take its place.” Legal meanings, then, cannot be extracted from the narratives that supply their context without suffering a fundamental loss of intelligibility. Today, amid the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown, the U.S. faces a reckoning with the narrative that has long provided the justifying context for the federal government’s immigration power.

From the outset, the “alien” has indicated a legal figure accompanied by an aura of suspicion. Perhaps fittingly, the term “alien,” is not native to US Law, but comes from the English Common Law. The “alien-born,” according to Blackstone, stood in contradistinction to the “natural-born subject,” differentiated by a natural and inassimilable difference: her liegence to whichever sovereign had dominion over the land of her birth. “An Englishman who removes to France or to China,” he writes, “owes the same liegence to the King of England there as at home, and twenty years hence as well as now.” Likewise, the person of France or China who removes to England. Characters with divided loyalties, aliens could not be trusted to have their new nation’s best interest at heart. Although US law replaces the “natural-born subject” with the “citizen,” the “alien” remains. At critical turns, as is the case today, the accompanying aura of suspicion has given way to the specter of enmity.

This view of the alien finds paradigmatic expression in Justice Stephen Field’s 1889 ruling in Chae Chan Ping v. United States. Field presents Chinese aliens as racial outsiders prosecuting a cultural invasion of the U.S. By establishing cultural enclaves and refusing to assimilate, these aliens had ostensibly set up colonies on US territory and threatened to undermine its sovereignty. The sovereign’s duty and right to repel such existential threats would ultimately provide the foundation for the Plenary Power Doctrine. Allowing that invaders do not always arrive armed and uniformed, Field’s ruling identifies alienage itself with the possibility of enmity. As if anticipating Carl Schmitt’s notorious identification of “alien” and “enemy,” Field laid the foundation for a legal landscape in which “aliens” are subject to extraordinary precarity—and enmeshed the “alien,” and the enforcement measures designed to exclude and remove them, in a narrative of attack and defense. Characterizations of aliens as “invaders,” “murderers,” “rapists,” and other sorts of malign actors bent on the destruction of the United States are of the audible echoes of this often unspoken narrative.

Today, in Trump’s second administration, the name “alien” is suffused with enmity, as it was in 1889. Mere hours after his inauguration, Trump issued an executive order titled “Protecting the American People against Invasion.” Alleging violence perpetrated by rampant “cartels, criminal gangs, known terrorists, human traffickers, smugglers, [and] unvetted military-age males from foreign adversaries,” the order declares that “America’s sovereignty is under attack” and calls for the armed forces to “take all appropriate action to assist the Department of Homeland Security in obtaining full operational control of the southern border.” What began in the borderlands swiftly spread to the interior. Buoyed by a staggering infusion of federal funds and ennobled by revocations of policies protecting “sensitive spaces,” including schools, hospitals, and houses of worship, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, better known as ICE, has, by its reporting, removed “over two million illegal aliens” from US territory in 2025.

Yet even if one celebrates this news, the invasion narrative poses a threat to migrants and citizens alike. In his concurring opinion to Noem v Vasquez Perdomo et al., Justice Kavanaugh includes “apparent race or ethnicity” and “speaking Spanish or speaking English with an accent” as reasonable grounds of suspicion for enforcement actions. However, Kavanaugh’s opinion fails to account for reported incidents in which such suspicions have precipitated the extended detention and removal of legal aliens—and even citizens. These incidents reveal the pernicious, antinomian effects of a narrative that tacitly identifies alienage, racial difference, criminality, and enmity. The “alien” is a cancerous legal figure that metastasizes and threatens to make race, rather than legal status or national origin, the grounds for identifying “friends” and “enemies.”

However, as this cancer spreads through the body politic, religious organizations yet possess distinct opportunities to slow the contagion. First, as story-shaped communities endowed with rich narrative imaginaries, religious organizations are well-resourced to provide a counter narrative about citizens and aliens that emphasizes compassion over enmity. Second, under the protections afforded by the First Amendment and Religious Freedom Restoration Act, religious organizations possess an opportunity to make their sanctuaries and houses of worship zones of exception wherein these narratives become effective. Between narrative and nomos, then, religious organizations may play a role in welcoming migrants into an otherwise hostile community, not merely through sectarian withdrawal, but open legal contest.

A Judeo-Christian Counter-Narrative

I have used the term “religious organizations” broadly up to this point, however, as a matter of scope and of my own expertise, I will limit my attention to briefly sketching out a counter-narrative available in the Judeo-Christian traditions. To do so, I focus on the figure of the gār as a paradigm for our humanity and for justice in the Hebrew Bible.

The term gār appears 92 times in the Hebrew Bible. Sometimes translated as “alien,” this translation proves misleading in our own legal context. Certainly, the gār is an outsider. She may be a “racial other.” However, paradoxically, her alterity does not necessitate suspicion or enmity but rather discloses participation in a common human condition. Whether in the tales of Abraham, Sarah, and the fathers and mothers of the faith, or of the people’s exiles in Egypt or Babylon, or of their wanderings in the wilderness, the Hebrew Bible is a story about sojourners. Thus, in Genesis and in Exodus, the term gār is applied to heroes of the faith. In the Chronicles and in the Psalms, it is used as an inclusive term to capture the transience and contingency that characterize all human beings:

For we are strangers before thee, and sojourners as all our fathers were; our days on the earth are all like a shadow, and there is no abiding (1 Ch 29:15 KJV).

Hear my prayer, O LORD, and give ear to my cry; hold not thy peace at my tears! For I am thy passing guest, a sojourner, like all my fathers (Psa 39:12 KJV).

In the phrase “all my fathers” and in the speakers’ juxtaposition before the divine, these passages make explicit what is implicit throughout the Hebrew Bible. The sojourner, the people of God, and all humanity are bound by relationships of synecdoche. Within these bonds, the vision of humanity that emerges is one in which crossing and not dwelling, transience and not permanence, contingency and not security are the marks of a shared human condition. Notably, Levitical and Deuteronomic law go so far as to preclude the ownership of any land in perpetuity. Land belongs to God and can be held only in temporary trust. Moreover, when this trust is broken, possession of the land may be revoked. (Lev 25:23 & Deu 28:43) Rather than meeting these facts with contempt, the Hebrew Bible makes them the basis for justice and compassion.

Thus, the people’s treatment of the sojourner (along with the widow and orphan), sets the paradigm for righteousness and unrighteousness. In multiple instances, the scriptures assert that there must be one law and one scheme of rights, obligations, and entitlements for the citizen and sojourner alike.1 E.g., Exo 23:9 & 48-49; Lev 16:29, 17:18, 17:10-18, 18:26, 20:2, 22:18, 24:16-22, Num 9:14, 15:14-30; Deu 1:16. If there is to be any differential treatment, it must be to achieve equity for those who, by virtue of their outsider status, face the precarities of landlessness and disinheritance.2 E.g., Lev 19:10; Num 35:15; Deu 10:18-19, 14:29, 24:19-21, 26:12; Jos 20:19. This imperative is typified in agricultural practices, like gleaning, that allow sojourners and other marginalized persons to survive on a land that is not their own. The love-command appearing in Lev 19:34 crystalizes the theological rationale for these legal institutions:

When an alien resides with you in your land, you shall not oppress the alien. The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God.

To be human is to be a sojourner on the earth. God’s “chosen people” are no exception. For them, this status is an historical and anthropological fact. To oppress the sojourner, then, on the grounds of her racial difference, would amount to a failure of collective memory that dehumanizes sojourner and citizen alike.

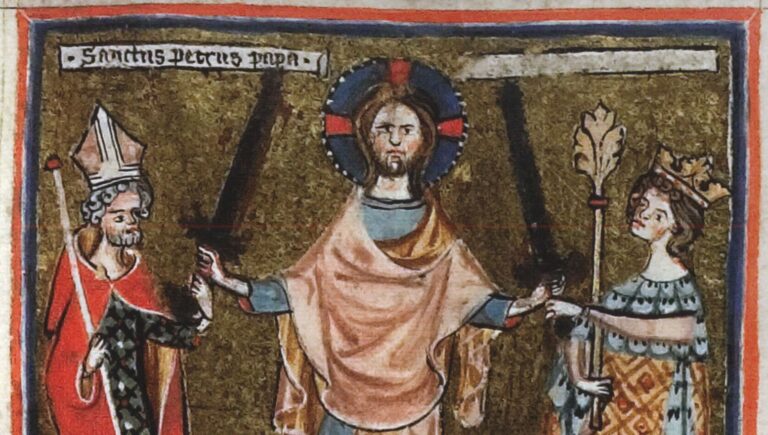

The Christian scriptures underscore this error’s full theological gravity. Throughout the Prophetic literature, Israel’s and Judea’s oppression of sojourners is presented as symptomatic of a broken relationship with the divine3 E.g., Eze 22:7 & 29 & Jer 22:3 . Likewise in the story of Christ. Jesus arrives as the ultimate outsider. The transcendent Creator now walks the Creation in human flesh. Yet the longawaited Messiah does not arrive as a conquering king in the mold of David. Instead, he is an itinerant wanderer. “Foxes have holes and birds of the air have nests,” as Jesus says in the gospels, “but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (Lk 9:58 NSRV, Mt 8:20 NSRV). Moreover, Luke’s gospel reinforces the divine’s identification with the outsider by emphasizing Jesus’s ministry with racial outsiders in Samaria. The Parable of the Samaritan goes so far as to make the Samaritan the paradigm of righteousness, confounding along the way legal distinctions between citizens and sojourners (123-126). The divine sojourner’s crucifixion, in turn, reveals the inhumanity of the Roman Empire.

According to the Judeo-Christian literature, God is encountered—perhaps literally—in the person of the sojourner. Thus, not only our disposition toward ourselves, but also our disposition toward the divine is revealed in the compassion or enmity with which we meet her. The crucifixion, then, marks a radical break with the divine and with our own humanity. Crucially, this break is final neither in the prophetic literature nor in the Christian scriptures. The prophets anticipate covenants restored and the gospels long for resurrection and reconciliation. This expectancy sets the terms for the Jewish and Christian counternarratives to the invasion narrative that predominates today. The story of migration is not a story of invasion and defense haunted by the specter of ineliminable enmity. Rather, it is a story of humanity’s reckoning with the transience and contingency definitive of its condition as a finite, interdependent creature. The encounter with the neighbor is at once an opportunity to be reconciled to the other and to ourselves—perhaps even to the divine other.

Insular Constitutionalism: Sanctuaries as Zones of Exception

This counternarrative promises to make itself effective in the instances that the form of communal life it demands collides with the law. The sanctuary movements that exist today are the legacy of one such collision. In 1982, Tucson Pastor John Fife, Quaker Rancher Jim Corbett, and a coalition of other religious leaders and laypeople publicly notified the Attorney General that they would convert their sanctuaries and houses of worship into safe havens for migrants fleeing the Northern Triangle of Central America. Appealing to the 1980 sanctuary act and referring to their activism as “civil initiative” rather than “civil disobedience,” they asserted that their actions were a civil application of a just law that the executive refused to apply. The Tucson Sanctuary movement’s legal gambit resembled what legal scholar Robert Cover referred to as “redemptive constitutionalism.” Like the abolitionist and civil rights movements before them, the Tucson Sanctuary Movement sought, through the mechanisms of the courts, to redeem the failings of the surrounding legal system. Though the movement dealt a blow to the Reagan Administration’s moral legitimacy and secured Temporary Protected Status for thousands of Salvadoran migrants, it did not yield substantive legislative change. In 1985, District Judge Earl Carroll found Fife, Corbett, and their co-defendants guilty of alien harboring, defeating the assertion that what they were doing was not only moral, but also legal.

Today, the effect that religious actors and organizations can hope to achieve is more modest. Recent legal battles in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands suggest that if the law does not provide a sword for positive legal change, it may yet provide a shield for those who would intervene against the most dehumanizing effects of the U.S. immigration enforcement regime. Arizona professor and humanitarian, Scott D. Warren has tested the promise of such strategies on multiple occasions. In 2019, after being arrested for providing food, water, shelter, and first aid to a pair of aliens unlawfully present in the country, Warren’s defense team lodged a Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) defense to ward off felony charges of conspiracy and criminal alien harboring. (After Warren’s initial 2019 felony case ended in a hung jury, the State dropped the conspiracy charge and tried him in a second trial limited to a pair of harboring charges. At this juncture, Warren’s team abandoned the RFRA defense.) In the same year, he won a second case using the same defense, this time in response to littering charges assessed for stashing water reserves on migrant trails in the western Sonoran Desert. Legal victories like Warren’s do not portend substantive changes to immigration statutes. Nevertheless, they do propose a strategy for making religious actors’ rights of conscience shields against the advance of government power.

The legal effort underway in New England Synod, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, et al., v. Department of Homeland Security, et al. promises to extend this strategy further. Plaintiffs argue that DHS’s revocation of the “Sensitive Spaces” policy undermines their capacity for the free exercise of their faiths, which require among other things the capacity to engage in collective worship with all persons, regardless of nationality or immigration status. As in Warren’s case, the plaintiffs in this case do not make a direct moral or legal assertion that the migrants in their midst ought to be admitted into the U.S. or exempted from removal proceedings. Rather, they appeal to RFRA and suggest that executing enforcement actions within their houses of worship will unduly burden their religious freedoms—even if DHS can be shown to be advancing a compelling government interest. However, by tying the integrity of their religious freedoms to the integrity of the “sensitive spaces” in which these freedoms are to be exercised, they place the shield which guarded Warren’s conscience at the sanctuary’s doors. Thus, a victory for the plaintiffs promises to make houses of worship into “zones of exception,” where the federal government’s sovereign power over aliens collides with the divine sovereign’s claim on the gār and is brought to a halt.

Such a result is not “redemptive constitutionalism,” but it is, nevertheless, a meaningful form of “insular constitutionalism,” a form of activism in which the law insulates one normative vision of life against government incursions. Whatever victories are won according to such a form of activism are limited. They do not change the hostile legal terrain that aliens unlawfully present in the U.S. must traverse. Nevertheless, they create waystations and shelters that declare the inhumanity of American justice and testify that the relationship between citizens and aliens could and should be ordered otherwise. ♦

Bryan Ellrod is Wake Forest University’s Director of Pre-Law studies. Working in this capacity, Dr. Ellrod endeavors to develop courses, advising, and co-curricular programming that would cultivate the excellences of character and mind necessary to equip students for their pursuits in the justice-seeking professions and to infuse their work with the ideal of pro humanitate. His current book project, “Can These Bones Live: A Political Theology for the US-Mexico Borderlands,” takes up these questions in light of the US border enforcement regime known as “Prevention Through Deterrence.”

Recommended Citation

Ellrod, Bryan. “Sanctuary as Insular Constitutionalism.” Canopy Forum, November 5, 2025. https://canopyforum.org/2025/11/05/sanctuary-as-insular-constitutionalism/.

Recent Posts