Selling Religious Cures and Other First Amendment Pitfalls in the Age of Coronavirus

Shlomo C. Pill

Photo by Anna Shvets (Pixels CC)

This article is part of our “Reflecting on COVID-19” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

Challenging times can bring out the very best in people, but these times also seem to prompt far less commendable actions by others. There are always those happy and eager to take advantage of a crisis, and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. Alongside stories of generosity and courage, there are reports of price gouging, fraud, baseless discrimination, and violence. Unfortunately, religious personalities of various stripes are not immune to such chicanery. Many religious leaders and communities are taking decisive measures guided by public health officials to slow the spread of the virus: they have halted congregational services, closed parochial schools, and offered private and public spiritual guidance to their followers during this challenging time. Others, however, have taken this opportunity to peddle in messianic and apocalyptic messages, downplay the value of official public health guidance, and offer religious panaceas that may run counter to good public health practice.

These unfortunate and potentially dangerous practices raise several First Amendment concerns that lie at the interaction of freedom of speech, religious liberty, and public health.

In one instance that has received some national attention, televangelist preacher Jim Bakker, host of The Jim Bakker Show, has been advertising and offering for sale a “Silver Solution,” which he and a “natural health expert” guest, Sherrill Sellman, have claimed “has the ability to kill every pathogen it has ever been tested on,” including the COVID-19 virus. On March 10, 2020, the State of Missouri sought an injunction against televangelist preacher Jim Bakker, prohibiting him from selling or advertising snake-oil remedies for COVID-19. Bakker has also received a cease-and-desist letter from the New York State Attorney General as well as warning letters from the Federal Trade Commission and Food and Drug Administration, all demanding that he stop promoting “Silver Solution” as a coronavirus cure.

Of course, long-standing First Amendment free speech doctrine maintains that commercial speech deserves less constitutional protection than political speech. In 1980 the Supreme Court decided Central Hudson Gas and Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission of New York and ruled that commercial speech that is false or deceptive does not carry any informational value and does not serve other important free-speech interests. Thus, false commercial speech—like Jim Bakker’s seeking of commercial gain by advertising and selling “Silver Solution”—can be banned or penalized by law. This is all the more true where banning such speech serves substantial government interests. In this case, preventing Bakker from advertising and selling a so-called “miracle cure” for COVID-19 that assuredly does not work is important to preventing greater panic and the undermining of government-coordinated public health efforts.

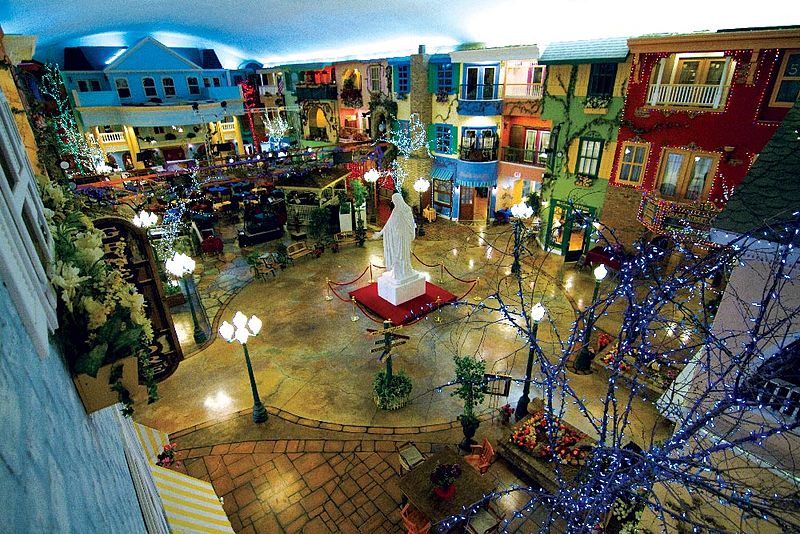

On the set of The Jim Bakker Show, Morningside, Blue Eye, Missouri, July 1, 2016 / CC-BY-SA-4.0

The Bakker case highlights other First Amendment concerns, which, while not directly present in Bakker’s purely commercial advertising of “Silver Solution,” are likely to come up in the coming weeks and months. Commercial speech is not fully protected by the First Amendment, and false or misleading commercial speech―like advertising that certain products or activities will provide benefits that they assuredly will not―is unprotected entirely. But what about religious speech? The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that religious teaching, counseling, and instruction are core protected First Amendment activities. But what about when religious teaching and counseling may be creating situations that threaten public health? What about when the religious activities of some faith leaders mislead constituents, undermine public health efforts, and risk exposing others to medical dangers―dangers that they thought prescribed ritual observances or donations to churches would protect them from? Can public officials take steps to restrict or penalize such conduct consistent with constitutional norms?

Here too, existing law provides some guidance. Prior to the Supreme Court’s 1990 ruling in Employment Division v. Smith, constitutional “free exercise of religion” protections precluded the government from directly penalizing religious activities absent compelling government interests. The courts have held that the protection of public health and safety are indeed such compelling government interests that may justify narrow restrictions on constitutional freedoms, including the First Amendment right to free exercise of religion. Smith, however, established that the government has even more leeway in its regulation of religious practices. If the law or regulation restricting religious practice is neutral (that is, it is addressing a policy concern other than religion per se) and does not aim to discriminate against religion, that law regulation is valid. Laws prohibiting fraud and restricting other activities that threaten public health and safety are typically of this kind; and even to the extent that they restrict religious teaching, which also enjoys free-speech protections, they may be constitutionally valid so long as they carefully target only so much religious speech and expression, as is necessary, to protect public health and safety from serious threats.

The courts have held that the protection of public health and safety are indeed such compelling government interests that may justify narrow restrictions on constitutional freedoms.

There is another angle to consider in connection to some religious leaders propagating and peddling ritual prescriptions and theological teachings that run counter to accepted medical realities and public health and safety efforts. Despite the typically privileged status enjoyed by religion and clergy in the United States, religious leaders can and have been held civilly liable to those harmed by their religious activities.

Courts across the United States have rejected the idea that clergy can be sued and held liable for clerical malpractice. Determining reasonable and appropriate standards of care for religious leaders treads dangerously close to government and law determining what religious practices are legitimate or normative and which religious functionaries are departing from “acceptable” religion. Such determinations are prohibited by both the First Amendment’s establishment clause as well as long-standing judicial avoidance of issues that require the courts to answer questions about what a religion teaches or demands of its followers.

Clergy and religious leaders can, however, be held liable for harming congregants and constituents to whom they owe special duties of care and to those that they know are especially susceptible to their influences. Consider one (in)famous and outlandish case reminiscent of Jim Bakker’s disingenuous attempt to take advantage of the current COVID-19 crisis for his own pecuniary gain:

In 1982, wealthy heiress Elizabeth Dayton Dovydenas joined The Bible Speaks church, which was then led by Pastor Carl Stevens, in Lenox, Massachusetts. Over the next several years, Stevens convinced Dovydenas to donate over $6.5 million to the church― in each case, Stevens stipulated as a matter of religious conviction that the gift would induce some positive outcome. In 1984, Dovydenas donated $1,000,000 to the church in order to cure Stevens’s wife’s migraines. In fact, the headaches continued, but Stevens told Dovydenas that her gift had cured them. In 1985, after Dovydenas told Stevens that she heard God tell her to gift the church with another $5,000,000, Stevens informed her that another of the church’s pastors was being tortured in a Romanian prison―she later donated the $5,000,000 to effect the pastor’s release. In fact, at the time that Stevens told Dovydenas this, the same pastor that was supposedly imprisoned in Romania was living safely on the church’s Massachusetts campus. Finally, later in 1985, Dovydenas made a $500,000 gift to the church to solve her marriage problems.

A federal appeal court ultimately invalidated the latter two gifts made by Dovydenas to Stevens’s church on the grounds that they were products of undue influence. Central to the court’s reasoning was the view that Stevens could not be permitted to take advantage of Dovydenas’s religious belief that her donations could impact temporal events like the pastor’s “imprisonment” or the condition of her own marriage. Though this may have been the donor’s own religious belief, Stevens knew that it was not guaranteed to work, as was evidenced by his wife’s continued headaches after the first donation of $1,000,000.

Neither religious practice nor religious speech (even if it isn’t commercial) is immune from legal and regulatory oversight.

There are vast differences between the Dovydenas case and most of the kinds of public pronouncements, directives, and instructions that are being issued and will surely continue to come from religious leaders at all levels across the United States. But as lawyers, policy makers, public health officials, and religious leaders consider such matters—whether the more egregiously commercial snake-oil selling of the Jim Bakkers of the world or the more well-intentioned pastoral and administrative advice and actions of other clergy—there are a few points worth keeping in mind.

First, neither religious practice nor religious speech (even if it isn’t commercial) is immune from legal and regulatory oversight, especially in the interest of public health and safety in a fluid and changing context. Many synagogues, mosques, and churches have shuttered their doors, and others may be asked to do so in order to slow the spread of the contagion. Religious leaders may be cautioned against or penalized for speech and teaching that advocates for illegal conduct or that poses genuine and imminent threats to public health and safety. Religion is often concerned with values that can at times be at odds with more of the material and pragmatic focuses of public policy-making. When such clashes create genuine dangers to public health, religion and speech may be constitutionally required to take a back seat on a limited basis.

Second, religious leaders should be weighing their words and actions carefully. To the extent that they recognize that others rely on them and their religious instruction and will make important decisions based on that guidance, clergy may bear the risk of liability for foreseeable harms caused by their directives. That a religious leader’s followers sincerely believe in the religious value of harmful religious guidance may not provide any protection. The Dovydenas case, in part, suggests that pastors, rabbis, imams, priests, and others may not avoid liability for providing misleading or dangerous religious guidance to their flocks that they have good reason to think is not effective simply because all those concerned believe in the religious truth of that guidance.

Religion is often said to bring out both the best and worst in humanity. In times of crisis and uncertainty, religious instruction and practice can offer welcome comfort, stability, and direction. Precisely for that reason, religious leaders of all faiths bear a great responsibility to dispense such advice responsibly and with proper account of the public health, ethical, and legal—as well as theological and ritual—considerations at play.

Shlomo C. Pill is a Senior Lecturer at Emory Law School and a Senior Fellow at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion. His teaching, research, lecturing and consulting work focuses on church-state issues, as well as religious law in both Judaism and Islam.

Want to participate in this ongoing discussion?

Submit an essay today!

canopyforum@emory.edu

Recommended Citation

Pill, Shlomo C. “Selling Religious Cures and Other First Amendment Pitfalls in the Age of Coronavirus.” Canopy Forum, March 16, 2020. https://canopyforum.org/2020/03/16/selling-religious-cures-and-other-first-amendment-pitfalls-in-the-age-of-coronavirus-by-shlomo-pill/