A ‘Bradburian Era’:

Media, Technology, and Censorship During the Coronavirus

Mark Edward Blankenship Jr.

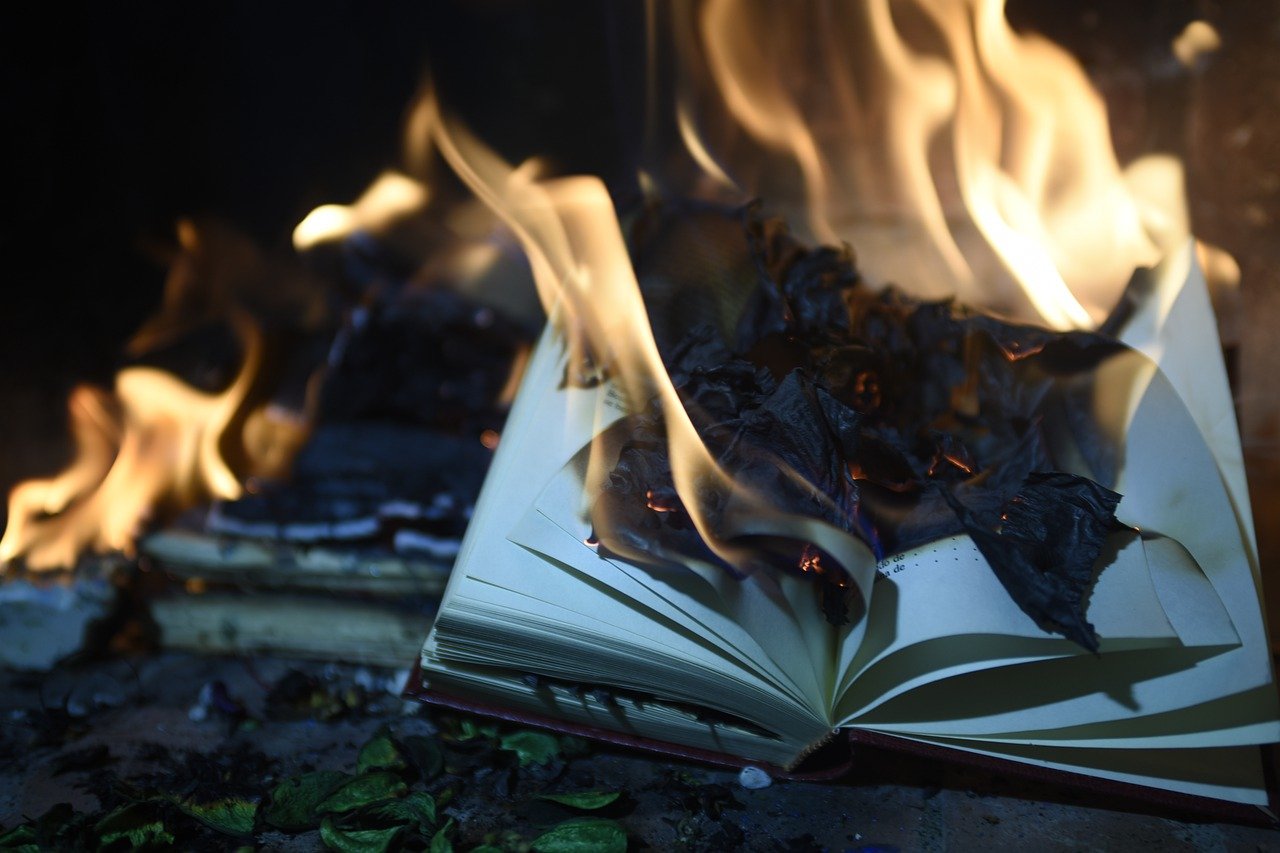

Image by Rafael Juárez from Pixabay.

This article is part of our “Law and Religion Under Pressure: A One-Year Pandemic Retrospective” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

Guy Montag comes home from work each day to greet his wife. The two unfortunately share no intimate connection with each other, nor any Biblical foundation in their marriage. Instead, Montag finds his wife constantly bombarded with flashing screens and television programs of counterfeit relationships and the cultural portrayals of family. Her disillusionment from the meaningless entertainment leaves her feeling indifferent to the people around her. She neglects her own mental and emotional state to the point that she numbs herself with pills and almost overdoses. Despite living under the same roof, both spouses seem to drift farther apart in the relationship.

Montag too suffers emotionally. He not only masks his feelings of unhappiness in his life, but he begins to doubt the value that his job is supposed to bring. At times, he feels like an outcast amongst his coworkers. His best efforts in keeping certain secrets eventually unfold, and as a result, he is forced to escape from tyrannical oppression, his wife’s betrayal, and police digital surveillance. In the end, he seeks haven in the countryside with a group of nomads, while discovering transformation through reading and memorizing the Bible.

Fahrenheit 451 is a dystopian novel, written in 1953 by Ray Bradbury, that portrays a world of godlessness, uniformity, consumerism, and the devastation that technology can have on the human psyche. The term “dystopia” was coined by English lawyer and social philosopher Sir Thomas More. Dystopias are often characterized by dehumanization, tyrannical governments, environmental disaster, or other characteristics associated with a cataclysmic decline in society. Other works of art that illustrate this type of community include George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and even the comedic film Idiocracy.

In Fahrenheit 451, certain acts, such as walking across the street, are considered illegal, and deep conversation and empathy toward others seem frowned upon. But the biggest legal offense that Fahrenheit 451 portrays is the outlawing and eradicating of books. The reason for this is that certain groups of individuals were offended by so many things in books, that they abandoned debate altogether. People also seemed to lack the reason to discern what is true versus what is false. By increasing the public demand for unsophisticated, uncontroversial, and hedonic forms of media, and having firefighters eradicate materials that could allow one to excel spiritually, intellectually, and practically over others, everyone could be equal. Education is then homogenized, history is rewritten, and anyone with a difference in opinion is treated as an outsider, if not a criminal. The novel’s setting is short from utopian, considering the war-like chaos Guy Montag eventually escapes.

The pandemic has already placed a strain on relationships and limitations on certain individual freedoms. Learning and communication has gone virtual. The isolation caused by quarantine and social distanced environments have led individuals to be fully reliant on technology in almost every aspect of their life from online grocery shopping and food delivery to online entertainment. Despite all of this, the actual world was less likely to be compared to Fahrenheit 451 in prior years.

Is describing this trend of book cancellation as “digital book burning” truly accurate?

But halfway through the new year, we have witnessed the call to ban several Dr. Seuss books, and perhaps the Curious George series too. A conservative author’s book critiquing transgenderism was removed by one of the most prominent online retailers, due to its alleged “hate speech.” Covid-19 survival guides and several books that questioned the severity of the Coronavirus have faced shutdowns too for providing “misinformation.” Yet books such as Charles Darwin’s The Evolution of Species and The Descent of Man and Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf are still sold on internet retailers, despite their “racist undertones.” Michael L. Brown, a professor in practical theology and Jewish apologetics, pondered the question that if such retailers were to ban books that criticized same-sex marriage, would the Bible be removed next, since it rebukes the practice of homosexuality? Furthermore, is describing this trend of book cancellation as “digital book burning” truly accurate?

Significance of Book Burning

In the middle of last year, former fans of the Harry Potter series began burning copies of the books, in response to author J.K. Rowling’s views of transgenderism. Yet book burning is a form of symbolic speech that is protected under the First Amendment. In 1990, the Supreme Court in Texas v. Johnson1491 U.S. 397 (1989). held that statutes which prohibited flag burning were unconstitutional under the First Amendment. But there is more to book burning than just a means of symbolic speech. Scholars point out that the core motivation for book burning is prioritizing one type of information over another. For example, in 213 B.C., Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang ordered a bonfire of books as a way of consolidating power in his new empire. Books of poetry, philosophy and history were specifically targeted, so that the new emperor could not be compared to more virtuous or successful rulers of the past. Other rulers like Adolf Hitler and Mao Zedong did the same thing. Essentially, any message that was labeled a “threat” to their ideology, was set ablaze.

But the burning of books is, as German author Heinrich Heine described, “mere foreplay.” Eventually, people and places are under attack. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, libraries across the nation have either limited access to people or faced complete shutdown. Public schools have pushed for more remote learning as a way to “reimagine education.” This has raised a number of concerns. The first has to do about what is actually being taught in school. Both conservatives and Evangelicals highlight that much of the curriculum is merely “propaganda.” But regardless of the veracity of this concern, there are other concerns that are perhaps more alarming. Students’ stress levels have increased, and mental health conditions have worsened due to remote learning. Furthermore, studies have shown that student proficiency in math and reading has declined since the pandemic. Not only does remote learning seem to ineffectively help students succeed academically, but reports also reveal that black, Hispanic, and poor children suffer more from remote learning.

Is the homogenization of education, like the kind found in Fahrenheit 451, what “reimagining education” in the future really about?

When taking a look at these factors, perhaps it is possible that the negative impact of the coronavirus on child education could snowball for decades to come. If that does happen, it then raises the question: how will public schools counteract against such a disproportionality in academic performance? Is the homogenization of education, like the kind found in Fahrenheit 451, what “reimagining education” in the future really about? And what procedures will schools put in place to reach this destination?

Media and Technology

Fahrenheit 451 noted that the use of book-burning as censorship was actually started by the general public, not the government. However, the government would eventually comply with public demand. Rod Dreher, a senior editor for The American Conservative, describes a similar phenomenon in his book Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents. Dreher illustrated this idea of soft totalitarianism, a means of censorship and religious persecution that is influenced by consumerism, corporations, and technology, rather than gulags. Furthermore, it “exploits decadent modern man’s preference for personal pleasure over principles, including political liberties.” Unlike the kind of totalitarianism2Totalitarianism is a form of government that combines political authoritarianism with an ideology that seeks to control all aspects of life. found in the Soviet Union, which was enforced heavily by the state, compliance with soft-totalitarian regimes is controlled by elites who form public opinion, as well as, powerful private corporations, especially those within the tech sector. Soft totalitarianism makes use of surveillance through advanced technology that is not imposed by the state (as of yet), but rather welcomed by consumers as aids to lifestyle convenience or for public health, especially in the post-pandemic environment. But is Dreher’s description of media influence accurate? Do these corporations have that much legal protection in creating such influence? Perhaps so.

Tech companies and social media platforms are protected from liability under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA), which prevents providers or users of an interactive computer service from being treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider. In addition, these companies are immune from civil liabilities for information service providers that remove or restrict content from their services they deem “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected”, as long as they act “in good faith” in this action. Section 230 is believed to be partly responsible for the issue of “fake news” and the statute has been under fire for quite some time.

The guarantees of free speech guard only against encroachment by the government and “erect no shield against merely private conduct.”

Furthermore, the First Amendment does not help in limiting such digital media influence. In fact, Internet users seem to have weak First Amendment rights against media platforms. The guarantees of free speech guard only against encroachment by the government and “erect no shield against merely private conduct.”3See Hurley v. Irish American Gay Group of Boston, 515 U.S. 557, 566 (1995). Tech companies are private actors; they are not a government entity or a political subdivision. In order for private action to be considered state action, there must be “a sufficiently close nexus between the State and the challenged action of [the private entity] so that the action of the latter may be fairly treated as that of the State itself.”4Blum v. Yaretsky, 457 U.S. 991, 1004 (1982). In 1996, a federal district court held that a private online company was not considered a state actor, because it exercised no powers that were the prerogative of the State.5Cyber Promotions, Inc. v. American Online, Inc., 948 F. Supp. 436 (E.D. Pa. 1996). That case also rejected the idea that communication accessways, such as e-mail, are not a public function, because alternative avenues of communication, such as telephone and mail, are still present.6Compare id. with Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946).

However, media platforms appear to have strong First Amendment privileges against Internet users. In Zhang v. Baidu.com Inc.,710 F. Supp. 3d 433 (S.D.N.Y. 2014). the plaintiffs, who were self-described promoters of democracy in China through their writings and reporting of pro-democracy events, alleged that the search engine blocked pro-democracy political speech from appearing in the United States at the request of the People’s Republic of China.8The PRC was named in the complaint and then never served, and thus, is no longer a party to the case. However, the Court held that the noble intentions of the government were irrelevant, and that search engines were protected from civil liability and government regulation under the First Amendment, because search engines utilize a certain level of editorial judgment in deciding what information to publish and what political ideas to promote. Thus, Baidu had a First Amendment right to skew search results for political reasons.

The Christian Church

Throughout the country, there are many households that could relate in some way to the Montags, as a result of Covid-19 and social distancing. Maybe it is the constant bombardment of movies, television, and social media. Or the bottling up of anxiety, depression, and insecurity. Is there a lack of purpose, fulfillment, or peace in life? In order for Christians to address these concerns and lead others to salvation, they must have the capability present God’s Word to them. However, statistics revealed that in 2020, the number of people who read the Bible is continuing to decrease. If Michael Brown is correct in asserting that the Bible is perhaps the next target for digital book burning, then this is not good for Christians, since their religious freedom could be undermined by the First Amendment privileges of tech companies and social media platforms.

During times like these, Christian churches must be strong in response to religious persecution and spiritual deception, continuing to innovate ways to lead people to Christ without compromising on Biblical values.

Another problem is that prior to the pandemic, efforts in presenting the Word eventually became miniscule in comparison to the entertainment and self-help motivation that churches hold in their buildings. Due to the emergence of COVID-19, churches have mostly held worship services online. While some churches have bounced back to holding in-person services, the numbers of congregants have definitely reduced. During times like these, Christian churches must be strong in response to religious persecution and spiritual deception, continuing to innovate ways to lead people to Christ without compromising on Biblical values. ♦

Mark Edward Blankenship Jr. is an attorney licensed in Missouri and is an LL.M. Candidate (Intellectual Property Law emphasis) at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University. He received his J.D. from the J. David Rosenberg College of Law at the University of Kentucky and his B.A. from Georgia Southern University. Additionally, he is the author and founder of The Holy Cross Xaminers, a blog on modern and contemporary issues pertaining to Judeo-Christianity, policy-making, and the law.

Recommended Citation

Blankenship Jr., Mark Edward. “A ‘Bradburian Era’: Media, Technology, and Censorship During the Coronavirus.” Canopy Forum, April 23, 2021. https://canopyforum.org/2021/04/23/a-bradburian-era-media-technology-and-censorship-during-the-coronavirus/