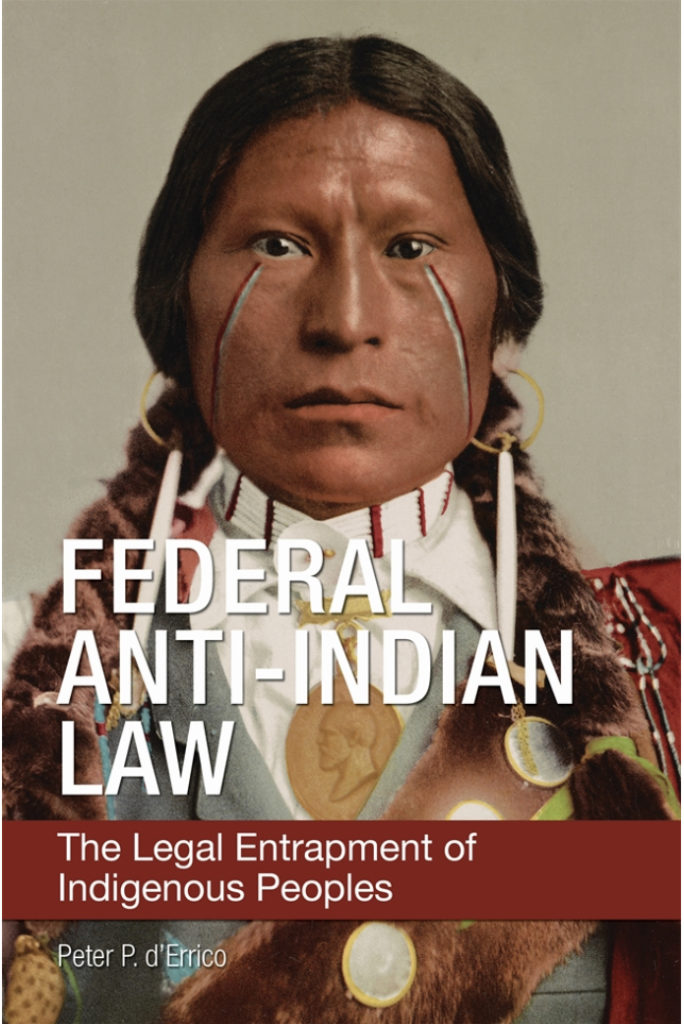

Federal Anti-Indian Law: The Legal Entrapment of Indigenous Peoples

Peter d’Errico

The following is an excerpt from Peter d’Errico’s Federal Anti-Indian Law: The Legal Entrapment of Indigenous Peoples (Bloomsbury, September 2022).

2023 is the bi-centennial year of Johnson v. McIntosh, the case that put ‘Christian discovery’ into US property law in a way that simultaneously created ‘federal Indian law’: The 200th year since the imposition of domination on the basis of a religious and racist theory of humankind. A domination that two-hundred years later is still considered ‘law.’

This book tells the story of Christian discovery, the legal doctrine underpinning U.S. dispossession and domination of Indigenous peoples. The doctrine, which essentially states that the United States owns all Native lands, haunts American law to this day. It forms the bedrock of what is known as “federal Indian law”; in fact, federal Indian law is a matrix for domination, which is why I call it “federal anti-Indian law.”

Federal anti-Indian law carries a significance far beyond the relations between the United States and Native peoples. Indeed, challenging Christian discovery and America’s claim to own Native lands and to have “plenary power” over Native peoples produces a metaphysical crisis for America. As one scholar said, “If the federal government . . . exercises unrestrained power over Indian nations, then . . . we have a different kind of government than we think we have.”

Stories of dispossession and domination of Indigenous peoples are often told (and often elided) when discussing American history. A crucial (and often overlooked) part of this genocidal history is the story of the legal doctrines underpinning this dispossession and domination. This book tells that story.

The first thing to understand is, as Professor Elizabeth Reese succinctly put it, “Federal Indian law is not really Indian law.” She quotes Vine Deloria, Jr.’s famous remark: “What is missing in federal Indian law are the Indians.” She goes on to note that “Indians and their tribes are the objects of federal Indian law, not its architects,” and “federal Indian law’s domination” consists of “laws the United States has come up with to legitimize or shape Indians’ conquest.”

Chief Justice Marshall constructed federal anti-Indian law in three early nineteenth-century cases. First came Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), a property law decision declaring that Native peoples did not own their lands after they had been “discovered” by Christian colonists. The second was Cherokee Nation v. State of Georgia (1831), which stated that Native nations were not independent of the United States and Native peoples were subject to U.S. “guardianship.” The third, Worcester v. State of Georgia (1832), declared “U.S. ultimate dominion” over all Native peoples and lands.

As the legal historian Paul Finkelman explained, “Marshall’s years on the court . . . coincided with a relentless push to remove Indians from the eastern part of the United States. Thomas Jefferson developed the idea of Indian removal. Under James Madison and James Monroe, the nation’s policy of war and removal devastated the southeastern Indians. President Andrew Jackson continued these policies. Marshall’s decisions in Johnson and Graham’s Lessee v. M’Intosh, . . . Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, . . . and Worcester v. Georgia . . . provided the legal basis for taking all land from Indians.”

In his 1992 law review article “The Evidence of Christian Nationalism in Federal Indian Law: The Doctrine of Discovery, Johnson v. McIntosh, and Plenary Power,” Steven T. Newcomb notes that U.S. law related to Indigenous peoples is “premised on the ancient principle of Christian dominion and a distinction between paramount rights of ‘Christian people’ and subordinate rights of ‘heathens’ or non-Christians.” He described the Christian/heathen distinction as “the tacit, underlying basis of all subsequent determinations of Indian right[s].”

In 1986, Professor Robert A. Williams, Jr., described the field as a “jurisprudence distilled from the heritage of Christian medieval legal mythology.” The foundations of U.S. legal doctrines related to Indigenous peoples, he said, “once revealed, would shame those who cite them.” That moment of shame has not yet arrived.

The United States has not yet disavowed the doctrine that claims Native lands are under its “ultimate dominion” and “guardianship.”; American courts at all levels continue to frequently cite the Marshall trilogy; the root word “Christian” is now usually redacted however, as in Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s opinion in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Nation (2005), in which she referred simply to “discovery.” She wrote, “Under the ‘doctrine of discovery,’ . . . fee title to the lands occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign — first the discovering European nation and later the original States and the United States.”

In the case 2020 McGirt v. Oklahoma, the Supreme Court relied on the “Christian discovery” doctrine without even using the word “discovery”; instead, it referred to the claim of domination only obliquely, calling it the “significant authority” of the United States “when it comes to tribal relations.” As we will see in Chapter 2, Justice Neil Gorsuch hid Christian discovery behind citations. As Newcomb pointed out, the religious foundation of the law “is seldom, if ever, explicit. . . . [It] remain[s] out of sight, below the level of conscious awareness. With few exceptions, [it is] never brought into contemporary discussions of the law.” Angelique EagleWoman, speaking of Canada and the United States, similarly noted that “what is often glossed over in the property law introductory lesson is the Christian formed ‘doctrine of discovery’ that continues in full force in both countries.”

The opinions in McGirt and City of Sherrill demonstrate another important point: Christian discovery doctrine in federal anti-Indian law spans the political spectrum in the United States. Sherrill was written by the liberal Ruth Bader Ginsberg, McGirt by the conservative Neil Gorsuch. As Professor Bethany R. Berger wrote, “The more liberal members of the Court . . . not only joined, but at times led, the charge against tribal interests.” She added, “Something beyond a liberal-conservative bias is going on here.”

The chapters in this book present four interrelated arguments:

- Federal anti-Indian law is an exception from the rule of law — it is a claim of unlimited U.S. power.

- Federal anti-Indian law has facilitated the genocide and attempted genocide of Native peoples.

- The doctrine of “tribal sovereignty” in federal anti-Indian law is really nonsovereignty — it is a relic of Native original free existence restricted and dominated by the U.S. claim of “plenary power.”

- Federal anti-Indian law remains the basis for the ongoing U.S. invasions of Native lands and domination of Native peoples.

To put this more explicitly, federal anti-Indian law is not ordinary law. It is the suspension of law — an assertion by the U.S. government of unlimited authority over Native peoples and lands. The trilogy of decisions written by John Marshall assigned Native peoples and lands to the arena of U.S. congressional politics, thereby sanctioning whatever federal policies that a majority in Congress might concoct. This is what permitted and sanctioned “Indian removal.” Marshall ignored ordinary common law principles of land ownership and instead adopted what the law professor Kent McNeil has shown to be a misunderstanding of English law and Crown powers.

As we will see, the suspension of law — the exception — has made federal anti-Indian law a jurisprudential mess. Its legal theories are ambiguous and contradictory. Legal terms like “trust relationship” and “government-to-government relations” have meanings in federal anti-Indian law diametrically opposed to what they mean in ordinary law. This has been pointed out at the highest level of the U.S. judiciary by Justice Clarence Thomas, who said in United States v. Lara (2004) that “federal Indian policy is, to say the least, schizophrenic.” Professor Angelique EagleWoman applied that same label in her critique of U.S. restraints on Native economies when she said that “federal policies schizophrenically have swung between imposing greater federal control of tribal resources and at the same time declaring a policy of tribal self-determination.” In the conclusion to Native American Sovereignty on Trial, his compilation of these cases, Professor Bryan Wildenthal argues that “as the twenty-first century dawns, the story of Indian tribal governments and their place within the U.S. constitutional framework is becoming ever more complex and paradoxical.”

This book will show that the often-noted confusion in federal anti-Indian law arises from trying to view the field as a set of legal rules when federal anti-Indian law is in fact characterized by the suspension of law and rules — an exception to the rule of law.

My analysis of this system of laws has repercussions for so-called “tribal peoples” worldwide. In the final chapter, I take a global view, drawing some lessons from the long struggle for Native survival and opening a vista for humanity to rearrange our relations with each other and with the planet that we share with the rest of Creation.

Despite the massive pressures arrayed against them, Indigenous peoples still exist, through what the Anishinaabe professor and writer Gerald Vizenor calls “survivance”: a combination of survival and resistance. The Osage/Cherokee law professor Rennard Strickland lauded Native peoples for having “learned the lesson of building and rebuilding a civilization, of adapting, of changing, and yet of remaining true to certain basic values regardless of the nature of that change.” He noted that “at the heart of . . . Indian values is an understanding and appreciation of the timeless — of family, of tribe, of friends, of place, and of season. It is a lesson that white civilization has yet to learn.”

Strickland’s remarks illuminate what the sociologist John Collier wrote in 1947 when he reflected on his experience as Bureau of Indian Affairs commissioner in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR)’s New Deal administration. Collier said that “the deep cause of our world agony is that we have lost that passion and reverence for human personality and for the web of life and the earth which the American Indians have tended as a central, sacred fire since before the Stone Age. Our long hope is to renew that sacred fire in us all. It is our only long hope. But the externals we have made our gods are in the saddle now. In our present crisis and out of our inadequacy we must try to sway the immediate event.”

How can timeless Indigenous values (which white “civilization” has yet to learn) be protected in the face of federal anti-Indian law not only in the United States, but throughout the world? That question guides this book. I offer it as a tool in what the Muscogee Creek medicine teacher Phillip Deere called “a rightful education.” ♦

For more, see the videos “Doctrine of Declaration Workshop” and “Creating a Human Rights Culture: A Look into Indigenous Peoples’ Rights” featuring Peter d’Errico and “The Doctrine of Discovery: Unmasking the Domination Code” based on Pagans in the Promised Land (2008) by Steven T. Newcomb.

This article is part of our “200 Years of Johnson v. M’Intosh: Law, Religion, and Native American Lands” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

Peter d’Errico graduated from Yale Law School, was an attorney at Dinébe’iiná Náhiiłna be Agha’diit’ahii, Navajo Legal Services, and a founding professor of Legal Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He litigated on behalf of Native prisoners’ freedom of religion; Mashpee Wampanoag fishing rights; Western Shoshone land rights; and other Indigenous cases.

Recommended Citation

d’Errico, Peter. “Federal Anti-Indian Law: The Legal Entrapment of Indigenous Peoples.” Canopy Forum, March 7, 2023. https://canopyforum.org/2023/03/07/federal-anti-indian-law-the-legal-entrapment-of-indigenous-peoples/.